- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Politics

- Review Article: Yes

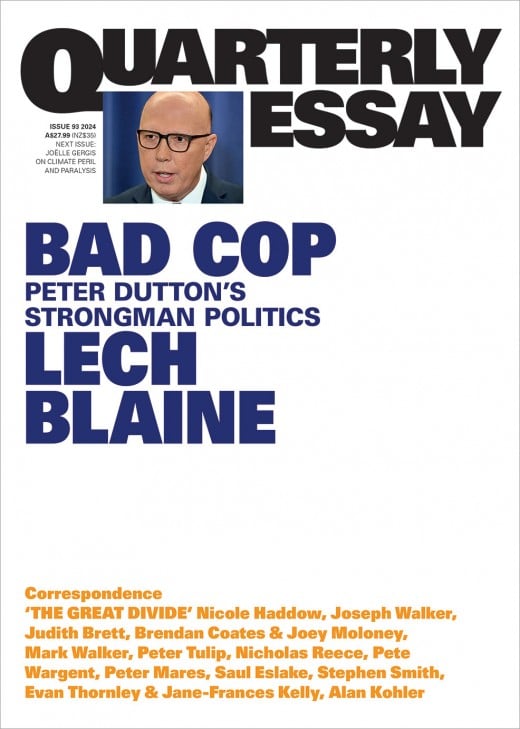

- Article Title: ‘Some grotesque Minotaur’

- Article Subtitle: Peter Dutton’s aggressive formation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Bill Hayden might today be recalled as the unluckiest man in politics: Bob Hawke replaced him as Labor leader on the same day that Malcolm Fraser called an election that Hayden, after years of rebuilding the Labor Party after the Whitlam years, was well positioned to win. But to dismiss him thus would be to overlook his very real and laudable efforts to make a difference in politics – as an early advocate for the decriminalisation of homosexuality, and as the social services minister who introduced pensions for single mothers and Australia’s first universal health insurance system, Medibank. Dismissing Hayden would also cause us to miss the counterpoint he provides to Peter Dutton, current leader of the Liberal Party.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Patrick Mullins reviews ‘Bad Cop: Peter Dutton’s strongman politics (Quarterly Essay 93)’ by Lech Blaine

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

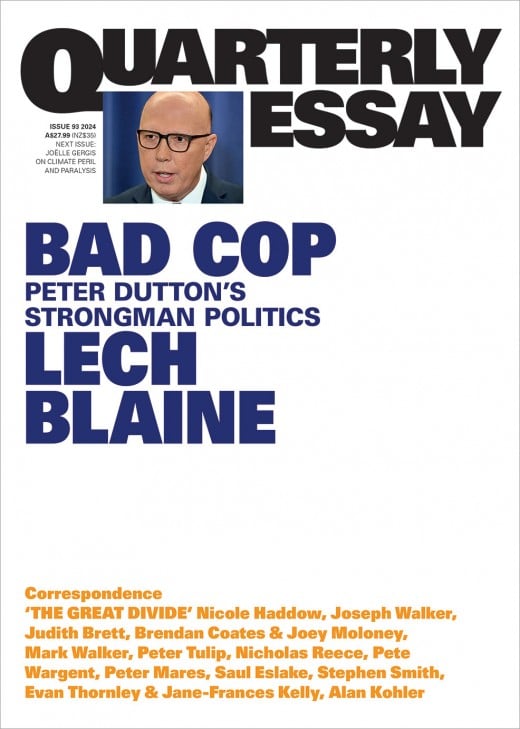

- Book 1 Title: Bad Cop

- Book 1 Subtitle: Peter Dutton’s strongman politics (Quarterly Essay 93)

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.99 pb, 176 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Lech Blaine’s timely and perceptive profile of the Opposition leader barely mentions Hayden, but the parallels between the two are striking. Queenslanders born in suburban Brisbane, both were middling students who became police officers at the age of twenty. After eight years for Hayden and nine years for Dutton, both left and went into federal politics as comparatively young men (Dutton after a two-year interregnum spent studying business at university and flipping properties with his father, an activity that has made him rich). They diverge in political allegiance and in what they took from their experiences in uniform. Where Hayden was wary of the copper’s suspicious instinct, commenting that exposure to society’s ‘grotty margin’ risked developing a ‘jaundiced view of life’, Dutton embraced it. ‘It does stay with you,’ he told Annabel Crabb on Kitchen Cabinet.

Dutton became, by his own admission, blind to shades of grey and apt to perceive danger wherever he looked. In a well-contextualised narrative of how this came to be, Blaine grants that the cases Dutton worked on – the sexual assault of a child, the murder of another – were harrowing, and argues that Dutton suffered injuries that were both physical (in a car accident sustained during a police chase) and psychological. There was a dramatic crisis of confidence arising from that car accident, which in 1999 spurred Dutton to leave the force, as well as a ‘sort of PTSD’, as Dutton has termed it, from his years of service. According to Blaine, in a punchy summation, the result is key to understanding Dutton: ‘[He] became a man frozen within a period of fear. Trauma made him soft. In lieu of psychological attention, control made him feel solid and safe again. Always displaying simplicity and strength. Because he feels so complicated and weak.’

The assessment is compelling on one level: since entering politics, in 2001, Dutton has reliably been a strong, blunt-speaking force for law and order. He has adopted as badges of honour the enmity of groups he lumps together as ‘the élites’, never takes a backward step, and is always talking of unscrupulous enemies and hidden dangers – from terrorists concealed among refugees to gangs on Melbourne streets to malevolent Chinese agents. It is certainly viable, psychologically, to infer that Dutton’s aggression stems from low self-esteem.

This assessment has its weaknesses. The focus on Dutton’s departure from the police force occludes the anxiety that manifested after his parents’ financial difficulties during his adolescence, and their subsequent divorce, which they announced when Dutton graduated from high school. More critically, that assessment is presented as the sole explanation for the man we see today.

Blaine places far too little emphasis, for example, on the structural incentive for Dutton to act as the ‘bad cop’. Law and order and national security have been political strengths for the conservative parties since at least the ‘red scares’ of the 1940s, and Dutton’s credibility on them has long fuelled his rise. It was not his pedestrian time as assistant treasurer (2006-7), under John Howard, that won Dutton admirers, nor his woeful time as health and sport minister (2013-14), under Tony Abbott: if anything, he was saved from ignominy in the latter case by a timely transfer to the immigration and border security portfolios. Dutton clearly believes danger is everywhere, but to attribute his actions and rhetoric solely to personal insecurity overlooks other important influences.

Blaine is on stronger ground when he identifies Dutton’s ambition, which can be – and has been – ignored thanks to more showy rivals and what Blaine termed, in his 2021 Quarterly Essay, ‘Top Blokes’, the camouflage afforded by the ‘monotonous rhetoric of the underdog’. This ambition almost certainly underpins key parts of Dutton’s political calculations: the April 2023 decision to oppose the Voice referendum was dressed up with invocations of egalitarian principle, but beneath it was Dutton’s need to unify the Liberal party room in the wake of the disastrous Aston by-election and to preserve his position as leader. History was not on his side: the last first-term Liberal Opposition leader to survive to a full parliamentary term was Andrew Peacock, in 1983-84.

In Dutton’s favour now is the lack of real internal rivals and his lack of interest in bringing back to the fold the inner-city seats lost to the Teal independent MPs in 2022: it frees him from any need to adopt the moderate policies that might divide his party room. Dutton’s determination to awaken new supporters in the outer-suburban and provincial electorates is clear enough, but the prospects that it will be a path to majority government are doubtful. Blaine shows that Dutton has an intuitive understanding of Queensland marginal seats, on the urban fringe, but cannot see his appeal in similar seats around Sydney and Melbourne, where electorates are culturally diverse and resistant to Dutton’s divisive rhetoric around race. The Opposition leader, Blaine concludes, somewhat paradoxically, is doubling down on his aggressive politics. ‘Dutton’s raison d’être? Make Australia Afraid Again. Then he will offer himself as the lesser of two evils. A serious strongman for the age of anxiety.’

This grim portent of the likely quality of political debate leading up to the next federal election is tragic for the Australian public and for Dutton. Among the many striking observations in this profile is how selectively Dutton applies his empathy. His professed fear that his own children might be kidnapped should have made him acutely alive to the experiences of the Stolen Generations, Blaine writes. That he was not – to the point that he boycotted Kevin Rudd’s 2008 apology to those generations – is indicative of the darkness that still surrounds the former police officer.

It is the key difference between Dutton and that earlier Queensland cop-turned-politician. Bill Hayden decided to leave the police force when he realised that he was haunted by a feeling of impending disaster. ‘As though some black grotesque Minotaur, stamping impatiently in the dark recesses of the unconscious, was waiting for the opportunity to charge, to smash me down, to trample over me,’ he wrote, later. ‘If only I could cling to the buoyant straw of faith in all this turbulence.’

Comments powered by CComment