- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Soul blindness

- Article Subtitle: Clerical narcissism and unfathomable cruelty

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

My first encounter with the writing of Anne Manne was ten years ago when I read The Life of I, her incomparable treatment of the various expressions of what she calls ‘the new culture of narcissism’. Some of the examples she adduces in that book are singularly monstrous – like the grandiose bloodlust of Anders Breivik or the sexual malevolence of Ariel Castro – while others are more like expressions of a dominant cultural logic, such as neoliberalism’s valorisation of self-sufficiency and the penalties it accordingly inflicts on both the vulnerable and those who care for them. But in each case she identifies a conspicuous failure of empathy, an incapacity (or perhaps unwillingness) to regard the moral reality of others such that it might present some constraint on the imposition of one’s will, some limit to the realisation of one’s designs.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Scott Stephens reviews ‘Crimes of the Cross: The Anglican paedophile network of Newcastle, its protectors and the man who fought for justice’ by Anne Manne

- Book 1 Title: Crimes of the Cross

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Anglican paedophile network of Newcastle, its protectors and the man who fought for justice

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $36.99 pb, 326 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781863959681/crimes-of-the-cross--anne-manne--2024--9781863959681https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781863959681/crimes-of-the-cross--anne-manne--2024--9781863959681#rac:jokjjzr6ly9m

It is this emptiness, this absence of empathy, that Manne locates at the core of narcissism. The ego, with its all-consuming claim to enjoyment or adulation, looms too large, and thus overwhelms any countervailing call for recognition or respect or even basic decency from the other person. As she writes, ‘Narcissism is all about the denial of another’s unique perspective on the world. It trashes it. It obliterates it.’ That is why the suffering of another human being holds so little interest for the narcissist, or why the other’s body can be used as a mere means to their own debauched ends, with impunity, and then be cast aside without a qualm. For the other person is not a person at all, but a thing which exists for the pleasure of what Iris Murdoch calls ‘the fat, relentless ego’. The viciousness of the narcissistic disposition is most powerfully conveyed in Manne’s analysis of male entitlement, coercion, and rape: time and again we see women’s expressed wishes and evident distress dismissed, their bodies treated ‘more with contempt than desire’ – and all the while the perpetrators console themselves that the experience of sexual degradation is, deep down, ‘enjoyable’ for their victims. Such is their moral insensibility in the face of the suffering they inflict on others, a condition the philosopher Stanley Cavell once called ‘soul-blindness’.

It is hardly surprising that Manne’s characterisation of narcissism should be so closely associated with contempt. Contempt, after all, is the contrary of attentiveness: the former leers at its object from a height, at once possessive and incurious; the latter lingers before the moral reality of another, humble, hesitant, wondering what response their pain, the particularity of their need, might demand. Indeed, for Simone Weil, the beginning of morality is the acknowledgment that ‘this man who is hungry and thirsty really exists as much as I do’ – ‘the rest’, she says, ‘follows of itself’. But, as Manne soberly reminds us, the opposite is likewise true: without the capacity or willingness to be attentive to the humanity of another person, ‘all manner of insensitivity, self-centredness and even human cruelty in relationships and politics become possible. What we call evil becomes possible.’

Though a decade separates them, I cannot help but see Crimes of the Cross as continuing with the same concerns that animated The Life of I. What Manne confronts when she turns her attention to the Anglican Diocese of Newcastle is the kind of wilful cruelty and unrelenting contemptuousness for which we rightly reserve the word ‘evil’ – an evil that was enabled, moreover, by a prevailing culture of priestly superiority, sexual licence, and open disdain for the people the church purports to serve. She calls it a form of ‘clerical narcissism’, and hundreds of children in situations of sometimes acute vulnerability suffered horrific abuse under its aegis. As Manne demonstrates, with conscience-searing precision, not only did the peculiar affordances of clerical life in Newcastle satisfy ‘the needs of narcissistic supply’, there was also a ready supply of children available to those predatory priests brazen enough to trade on the trust and comity of their church-attending parents, or else take advantage of the unfettered access they were granted within church-run institutions.

The details of the sexual abuse committed by this ‘dark network of paedophiles’, which operated in the shadows of the Newcastle diocese between the early 1970s and the late 1990s, are difficult to read and impossible to forget. But Manne goes on to show how that abuse was perpetuated and ultimately exacerbated by the craven sycophancy of a ‘grey network of clergy and lay protectors’ determined to cover it up. On both counts, the message could not be clearer: the welfare of children matters far less than either the standing of male priests or the good name of the church. And yet for all that, it is part of the moral achievement of Crimes of the Cross that Manne refuses to allow the malign narcissism of the perpetrators to dominate the story she means to tell. Given that paedophiles are intent on obliterating the agency – the very souls – of their victims, isolating them within a universe of helplessness and shame over which their egos can then hold godlike sway, it is only fitting that Manne’s narrative should be borne along by the courageous, truthful, self-deprecating voice of Steve Smith.

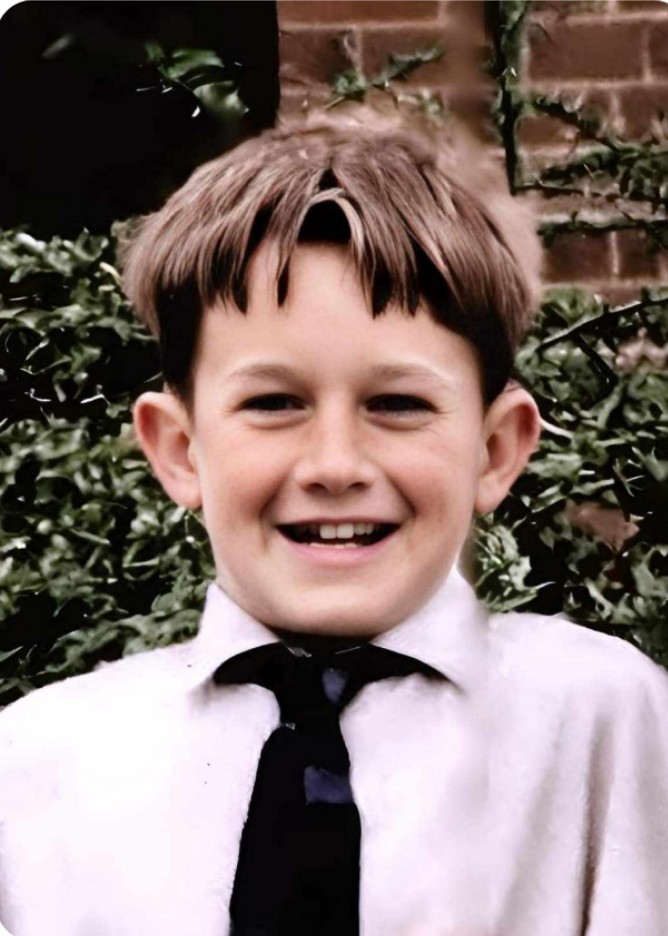

Between the ages of ten and fourteen, Steve was raped hundreds of times by the priest who presided over the adjacent Anglican parishes of Edgeworth and Gateshead, Father George Parker. As he recounts the sexual assaults he endured and the terror they induced, Steve articulates not only his own sense of powerlessness but the realisation that it was, in fact, ‘the power [Parker] got off on’. ‘It was so impersonal,’ he tells Manne. ‘It was entirely about him, what he wanted or needed … It didn’t matter what I felt or how upset I was, how painful, like I was an object.’

In this respect, of course, Steve was hardly alone. Variations on the experience of abject dehumanisation are repeated throughout the book: of children being drugged and then raped while unconscious, of their desperate pleas for their abusers to stop going unheeded, of boys shrinking in fear before their abusers’ lascivious touch or fleeing through dense thickets in order to avoid being caught and violated; and later, of grown men pleading for acknowledgment of the abuse they suffered as children and for remorse from the priests who had abused them, only to be met with clerical indifference, legal obfuscation, threats, intimidation, and outright lies. As Steve would later tell the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse: ‘I have found the process of dealing with the church as abusive as the sexual abuse itself. I was made to feel that the offences against me were worthless, because I was a boy abused by a priest who was protected by the church. I was also left with the impression that my life was worth nothing to the church.’

Having followed the Royal Commission closely, I was quite familiar with what had taken place in Newcastle. Nevertheless, on page after page of Crimes of the Cross I found myself wondering what could account for the sheer inhumanity of such responses to another human being, whether adult or child, in a state of deep distress. It cannot be that the perpetrators were merely ignorant of the compound traumas that sexual assault inflicts on the body of its victim or that they lacked an awareness of what Manne describes as the ‘horrifying cascade of psychic pain and neurophysiological change’ that rape survivors experience, preventing them from ever ‘moving on with their lives’. I often think of the distinction Stanley Cavell makes between a failure to know the pain of another person and a failure to acknowledge that pain. A ‘failure to know’ could simply be a matter of ignorance, ‘an absence of something, a blank’; but a ‘failure to acknowledge’ suggests ‘the presence of something … a callousness … a coldness’. Cavell continues: ‘Spiritual emptiness is not a blank.’ Doesn’t this point to the nature of the evil that had taken root over decades in the Newcastle diocese: an overweening institutional egotism that did not just derive a certain pleasure from the power it exercised over others, but also luxuriated in its imperviousness to the pain others had to endure? Put otherwise: a fundamental absence of empathy?

Steve Smith (courtesy of Black Inc.)

Steve Smith (courtesy of Black Inc.)

One of the most touching aspects of Manne’s book is her portrayal of the way Steve Smith responded to those who – following what she refers to as the ‘cultural revolution in our understanding of child sexual abuse’ during the early 2000s – showed him empathy: with wonder that he should be believed; with gratitude to have found a fellow human being; and with a palpable longing for solidarity in the cause of seeing justice done. But empathy here should not be mistaken for some kind of well-meaning condescension, much the same as we often think of pity. Instead, it represents an affirmation of Steve’s brave if battered humanity, and an undiluted sorrow for all he had endured. The incalculable moral importance of the Royal Commission was to have replicated this experience for so many of the 1,300 survivors who appeared before it. Each one was afforded the opportunity to bear witness through their pained testimony or their eloquent tears to the dehumanising evil of child sexual abuse and the culpability of those institutions that either tacitly or actively condoned it.

The Royal Commission thus exhibited an unfailing attentiveness to the experience of survivors that surpassed the meagre and invariably compromised responses proffered by the churches – tainted as they so often were with the ultimate goal of protecting the church’s reputation or minimising its legal exposure. These are but lesser expressions of the same self-protective approach (which Manne memorably terms ‘Team Church’) that would see the bodies of children repeatedly offered up on the altar of clerical narcissism. Little wonder, then, that the predominant cultural attitude towards the public pronouncements of Christian churches in the aftermath of the Royal Commission has been neither antipathy nor a kind of atheistic zeal, but rather ethical indifference.

When I finished Crimes of the Cross, having found myself repeatedly moved by Anne Manne’s tenderness towards Steve Smith and her moral incredulity in the face of the conduct of representatives of the church, I’ll confess that a different credo came to mind, an alternative statement of belief that would have served the victims of clerical cruelty and institutional contempt far better than the Christian creeds. It comes from a letter Anton Chekhov wrote to Alexey Pleshcheyev in 1888: ‘My holy of holies is the human body … love and complete freedom – freedom from violence and lies, no matter what form these two last may take.’ Imagine how different ten-year-old Steve’s life would have been had the vulnerability of his young body elicited the reverence it was owed, had his childhood been safeguarded from the violence of ordained narcissists and the lies of their patrons and protectors. Now that’s a creed worth believing in.

Comments powered by CComment