- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Nothing but kestrel

- Article Subtitle: Kevin Hart’s invitation to read contemplatively

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is a moment early on in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 (1953) – think of it as the novel’s opening gambit, the disturbance which sets its plot in motion – when the impish Clarisse McClellan attempts to rouse the book’s stolid and otherwise self-possessed protagonist, Guy Montag, from the partial oblivion in which he lives his life. She shadows him on his walk home from work one evening, verbally prodding him in the hope of puncturing what is evidently less a form of sincere conviction than it is a state of unthinkingness. After Montag rebuffs her questions one time too many, Clarisse finally complains, ‘You never stop to think what I’ve asked you.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Scott Stephens reviews ‘Lands of Likeness: For a poetics of contemplation’ by Kevin Hart

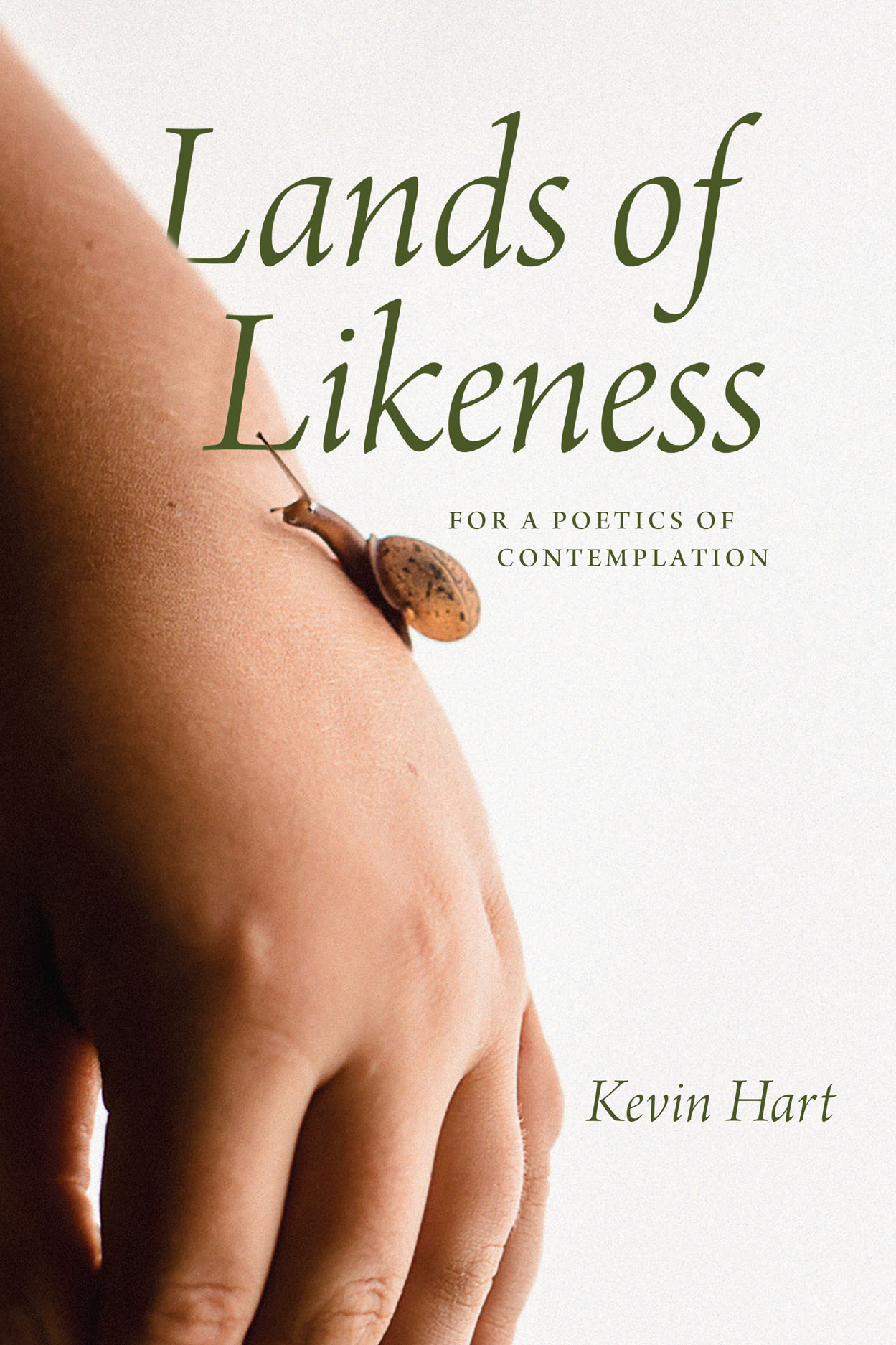

- Book 1 Title: Lands of Likeness

- Book 1 Subtitle: For a poetics of contemplation

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, US$37.50 pb, 427 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The conversation and pages that follow make clear just how intimately connected stopping is to thinking in the world these characters inhabit. High-speed cars have turned the natural world into an undifferentiated blur. Interactions with omnipresent screens have taken the place of both casual sociability and more intimate conversation. The steady stream of entertainment and ready availability of analgesics promise to palliate occasional bouts of boredom, melancholy, introspection, or doubt. Books have all but disappeared, and reading no longer exists as a solitary, discrete activity. People look at words, rather than read them. In Montag’s world, the very possibility of the cultivation of an inner life – of being alone with one’s thoughts, as it were – has been eradicated, not least due to the ubiquity of devices sometimes referred to as Seashells, small ‘thimble radios tamped tight’ upon people’s ear canals which emit ‘an electronic ocean of sound’, wave after wave of ‘music and talk and music and talk’ that successively flood the mind, replacing thought with noise. It is only once Montag stops, or is stopped by Clarisse’s provocations, that the rudiments of interiority (he calls it ‘that other self’) begin to stir and he starts to see the world, and himself, in a different light.

It is oddly fitting that seventy years later, at a moment when so many aspects of Bradbury’s vision of a post-literate society seem to have been realised, the acclaimed Australian poet and theologian Kevin Hart should deliver a provocation of his own, a similarly arresting invitation to stop and see. Lands of Likeness is a book that is profoundly unsuited to our times – with its extended explorations of Platonic philosophy and medieval spirituality, its frequent etymological digressions, and its achingly slow perambulations around the broken lines of post-Romantic poetry. And yet, for just that reason, it could not be more timely. For what it commends is nothing other than a way of being in the world that is neither grasping nor hurried, that is minutely attentive to the particularity of things rather than forever looking past them or behind or beneath, that constrains egoism in order to create space for the kinds of encounter that leave us transformed in their wake. It is a book that means to stop us in our tracks, permitting us to look, to linger, to wonder at what is. Or, as Hart rather touchingly writes, for all its theoretical sophistication and immense learning, Lands of Likeness is finally a book ‘about leaves and trees, birds and snails’.

This way of being in, and seeing, the world Hart calls contemplation. It is a term that is meant to strike our ears as strange, evoking both a time and a set of intellectual disciplines – among which are the cognate practices of meditation and consideration – altogether unlike our own. In our ‘intensely visual culture’, as Hart puts it, with its ‘preoccupation with screens of all sorts’, fascination is more the order of the day. What fascinates us holds us in its thrall, repelling us or eliciting our desire, or else ‘blankly captivating’ us such that we can neither entirely enjoy our interaction with it nor pull ourselves away. Objects of fascination need not be lurid to draw us in and wear us out; even casual binge-watching and incessant scrolling convey ‘a vague sense of pointlessness and endlessness that tires the intellect and the will alike’.

Contemplation, on the other hand, is a curious mix of attentiveness (the undivided orientation of the self, even for a short time, of the kind Simone Weil likened to prayer) and disinterest (not indifference, but a state of non-possessiveness). Which is to say, there is no desire to consume the object of contemplation; what there is, is a longing to understand. And by understanding, we are ourselves changed.

This points directly to the paradox at the heart of the title of the book. Acquisitiveness is a matter of taking that which enjoys its own integrity and beauty, and reducing it to something that exists for us and our use – call it a form of idolatry, the refashioning of a thing after our own image, thereby disfiguring it, rendering it unlike itself. In turn, the very act of attempting to become sicut Deus, God-like, through seizure, Hart writes, ‘is an act of rebellion against [God], for the impulse comes from the self, not from love, with the consequence that one becomes more unlike [God]’. (This, I suspect, is what Weil had in mind when she suggested that various forms of vice are ‘in their essence, attempts to eat beauty, to eat what we should only look at’.) By contrast, through contemplation we are lovingly absorbed by the beauty and integrity of the thing itself – what the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins calls its inner landscape, its inscape, ‘the specific mixture of properties, held together as one’. This contemplative journey into its inner space, for Hart, allows us to ‘step into the lands of likeness: we become for a short while what we behold’.

Part of the genius of Hart’s book is the way it transposes the language of contemplation – and the mystical experience such language implies – into the activity of the slow reading of poetry as a way of ‘facilitating this aesthetic beholding of the world around us’. The bulk of the book is taken up with articulating what Hart calls a ‘hermeneutic of contemplation’ in conversation with three thinkers (Arthur Schopenhauer, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Edmund Husserl) and then putting it to the test with three long poems (Wallace Stevens’s ‘Notes Toward a Supreme Fiction’ [1942], A.R. Ammons’s Sphere: The form of a motion [1974], and Geoffrey Hill’s The Mystery of the Charity of Charles Péguy [1983]). The symmetry of this arrangement is undeniably pleasing and effective. But at the heart of Lands of Likeness is the particular affinity Hart adduces between the twelfth-century medieval theologian Richard of St Victor and the nineteenth-century poet-priest Gerard Manley Hopkins – not least through the recurring motif of the bird in their writings. Richard, for example, likens the soul’s loving attentiveness to the mystery of God to the flight of birds in the heavens: ‘how often they repeat the same or similar circuits now a bit wider, now a bit narrower, always returning to the same point’. Hopkins, for his part, writes, ‘Let me be to Thee as the circling bird’ (1865), and his sonnet ‘The Windhover’ (1877), about a kestrel in flight, can be read as a figure of the mind in contemplation, ‘absorbed ... taken up by, dwell[ing] upon, enjoy[ing], a single thought’.

The image is a salutary one, for it beautifully captures something of the transformation that can occur through the exchange between the object and the subject of contemplation. The moral philosopher Iris Murdoch, for instance, uncoincidentally describes looking out her window ‘in an anxious and resentful state of mind ... brooding perhaps on some damage done to my prestige’. When suddenly, she observes a kestrel hovering on the currents of the air. ‘In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel.’ In this way, contemplating the figure of the kestrel enacts what Murdoch elsewhere calls a process of ‘unselfing’, a certain diminishment of ‘the fat, relentless ego’ in the face of the moral reality of another.

At the same time, the figure of the kestrel exemplifies the activity of contemplation itself as a peculiar form of work – not acquisitiveness or striving, but the kind of labour that suggests a profound and underlying contentment. Which is to say, a state of rest. Thus watching the birds in flight, Richard of St Victor writes that it is ‘as if by steadfastly accomplishing their work they precisely seem to cry out and say: It is good for us to be here’.

Lands of Likeness similarly performs the practices of loving attentiveness it commends to its readers. To read this book is to learn how to read contemplatively. But standing as we are at the precipice of our own post-literate age, with its screens and its speed, I fear that Kevin Hart’s invitation to stop and see may ultimately be asking too much of us.

Comments powered by CComment