- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘At least I’ve told these stories to you’: Pramoedya Ananta Toer and the Buru Quartet’

- Review Article: No

- Article Title: ‘At least I’ve told these stories to you’

- Article Subtitle: Pramoedya Ananta Toer and the Buru Quartet

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What was the best decision Brian Johns ever made?

In 2005, Johns – legendary leader of Penguin Books Australia, publisher of Elizabeth Jolley, Thea Astley, Frank Moorhouse, and so many others, and later managing director of the ABC and SBS – nominated his publication of the Buru Quartet, by Indonesian author Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Johns was speaking at an event for Pramoedya’s Indonesian editor and publisher Joesoef Isak, who was receiving the inaugural PEN Keneally Award for publishing. This may have been a case of politeness on Johns’s part, but there are reasons to think this was likely a more considered assessment.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): ‘‘At least I’ve told these stories to you’: Pramoedya Ananta Toer and the Buru Quartet’ by Nathan Hollier

The novels take their name from the prison established on Buru, one of the Maluku Islands, after Major General Soeharto seized power in Indonesia on 1 October 1965.3 Pramoedya was imprisoned there, along with his friend, political ally, and publisher, Hasjim Rachman, and thousands of other political prisoners. Pramoedya wrote the novels while in the prison. Just nine months after being released in 1979, he and Hasjim formed a publishing company with Joesoef and published the first novel of the quartet. Its cover bore the audacious words ‘A novel from Buru Island’.

Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind) was met in Indonesia with a glowing reception from prominent intellectuals in major publications. Lane, soon to be recalled to Australia for having ‘undiplomatically’ translated Bumi Manusia into English, remembered it as ecstatic. Indonesian Vice-President Adam Malik stated at the time: ‘Our youth, by reading this, will understand how their fathers confronted colonialism.’ The North American rights were purchased by William Morrow and Co., and there also the novels were recognised as masterworks, ‘one of the 20th century’s great artistic creations’, in the words of a Washington Post reviewer: ‘a work of the richest variety, color, size and import, founded on a profound belief in mankind’s potential for greatness and shaped by a huge compassion for mankind’s weakness’. Widely spoken of as a prospective winner of the Nobel Prize, in 1995 Pramoedya received the Ramon Magsaysay Award, often referred to as the Asian Nobel Prize. By the 2000s, the quartet had been translated and published into many languages and territories.

By contrast, each of the novels was banned in Indonesia shortly after their release. With the end of the Soeharto regime and the arrival of Reformasi in the wake of the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s, they could be sold in that nation again. I bought the US Penguin edition of This Earth of Mankind in a Periplus bookshop in Yogyakarta in 2018 and after reading it immediately ordered the following three novels: Child of All Nations (Anak Semua Bangsa, 1980), Footsteps (Jejak Langkah, 1984), and House of Glass (Rumah Kaca, 1988).

In prison on Buru, unable to find writing materials or a space to work, Pramoedya composed the novels in his mind and spoke them to the other prisoners in the large hut they shared. What drove Pramoedya to do this, within the brutal, oppressive conditions of the prison? ‘I’ve been working on these stories for a while,’ he replied when Hasjim asked him this question at the time. ‘Who knows, I might not survive long in Buru. If I die, at least I’ve told these stories to you.’

There, then, is part of the answer.

At the time of his imprisonment, Pramoedya was already a well-known author and journalist within Indonesia. He had published novels, memoir, reportage, and social commentary (including in defence of the Chinese in Indonesia, which had resulted in his imprisonment for nine months in 1960) and a collection of his newspaper essays on Raden Adjeng Kartini (1879–1904), the first Indigenous intellectual of the Dutch Indies whose writings were influenced by Enlightenment thinking. Pramoedya edited the cultural pages of the major daily Bintang Timur (Eastern Star) newspaper, published by Hasjim, and wrote regular essays for that paper, mainly on figures forgotten or, rather, written out of Indonesian history during Dutch colonial rule.

One such figure was Tirto Adhi Soerjo (1880–1918), who would provide the inspiration for Minke, the central character of the Buru Quartet. Soerjo, a Javanese of noble heritage, was one of the few Indigenous people of the Dutch Indies in the nineteenth century to obtain an education at an élite Dutch colonial Hogere Burger School (HBS). He later trained as a doctor in Batavia (today’s Jakarta), before working as a journalist. He founded the first formalised native business network, the Islamiyah Traders Union, or Sarekat Islam, and the first newspaper in the Dutch Indies to advance a native perspective and agenda informed, like the writings of Kartini, by an awareness of the world outside the Indies and of the possibility of a new, independent Indies nation.

Pramoedya’s novels take place over the period from the emergence of Kartini, at the end of the 1890s, to the end of the 1910s, by which time the colonial regime had cracked down on Soerjo’s and Minke’s newspaper and effectively sabotaged Sarekat Islam, the first Indies mass nationalist movement. At its height, Sarekat Islam had hundreds of thousands of members and was probably the largest political organisation in the world.

However inspiring the achievements of Soerjo – who remains an idol for many Indonesians today – Pramoedya’s greatest interest in researching this man’s life was in obtaining an understanding of the historic impetus for the creation of the state of Indonesia and, on the basis of that, an understanding of why Indonesia was not developing as he believed it could and should. Why in 1965 was this new nation still stubbornly backward and corrupt? Pondering this question, Pramoedya seethed with anger and wonder.

After This Earth of Mankind, which sets the scene of colonial oppression, the plot of the later novels is driven by Minke’s dawning awareness of the need to create Sarekat Islam as an inclusive, democratic mass organisation to properly represent the interests of all the people of the Dutch Indies and to realise their national and individual hopes and aspirations. A child of all nations, powerfully influenced in the novels by women intellectuals and leaders as well as men, Minke is inspired by the ideals and achievements of the French revolution and by the Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese resistance to European oppression, while also made conscious of Japan’s own imperialist tendencies.

By the end of the novels, what stands in the way of such a democratic body has become apparent: the colonial regime, certainly, which foments ethnic and religious identity and division in underhand and grossly dishonourable ways, but also superstitious, insular, tyrannous local tradition. Speaking of the peasant people of the Indies, ‘treated like cattle’ by the colonisers, Minke asks himself: ‘Was their situation any better before the people and land of the Indies had fallen into the grip of the Dutch? My teachers at school had taught that things had been worse. The rajas had never cared about the health and welfare of their subjects – only about how to rob them and use them for royal pleasure. And, damn it, I had to agree with my teachers.’

A novel, as Thomas Hardy said, is an impression, not an argument. One should be wary of seeking to systematise a novel’s themes (as also of critics who lord it over a novelist for not presenting an internally coherent academic treatise). Nonetheless, it is a great strength of the Buru Quartet that Pramoedya advances, through the experience and consciousness of Minke and other characters, a powerful conception of Indonesian and world history as it is and as it might have been. Minke works for the creation, within the Dutch Indies, of a properly inclusive nation, not a romanticised version of a pre-colonial past, in which all members have an equal formal and informal citizenship status, regardless of their race, religion, wealth, traditional social position, or gender, and an equal investment in the development of their nation and its people.

Imagining Pramoedya, imprisoned on Buru Island and unable to write, but aware of the social, historical, and aesthetic importance of his creative conception for his new nation, we can more fully understand how he found the will to recite his novels to his fellow prisoners, lest he die before he could write them down. In 1973, after eight years in Buru, Pramoedya was given a space to write, and a typewriter. Quickly, with barely a revision, the novels were typed out, using every ounce of paper margin.

When Pramoedya, Hasjim, and other Buru prisoners were released six years later, in December 1979, it was not because of any liberalising wind in Soeharto’s palace. International pressure, especially from the US Congress (led by Minnesota Congressman Donald Fraser), and the practical challenge of putting thousands of people on trial without evidence, meant that continuing this large-scale incarceration was not feasible. Soeharto and his allies and enablers within Indonesia settled for a renewed crackdown on dissent.

This was the environment in which Pramoedya, Hasjim and Joesoef came together in Joesoef’s tiny office in Jakarta to form the publishing firm Hasta Mitra (Hands of Friendship) and to publish the Buru Quartet. At the time of Soeharto’s coup in 1965, Joesoef had been secretary-general of the Asian–African Journalists Association and Vice President of the International Organization of Journalists. When asked about his first reaction to reading the manuscript of Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind), after his own ten years’ jail in Jakarta, Joesoef said: ‘I can’t describe it in words. It made me feel alive again.’ Pramoedya’s fellow prisoners had had a similar response.

The novels were gripping, moving. They had a unique importance for Indonesian readers. And they were going to be released into a cultural and intellectual wasteland. In his account of the life of the Buru Quartet, Lane powerfully conveys the dramatic nature of the change in Indonesia wrought by Soeharto’s seizure of power:

On the morning of 30 September 1965, President Sukarno was the overwhelmingly popular leader of the country with tens of millions of enthusiastic supporters. More than half the population had joined political parties or mass organizations that supported Sukarno and Socialism ala [sic.] Indonesia. While there was opposition to Sukarno, and it had incurred some restrictions, his popularity was massive and genuine. His ideas dominated. His speeches were listened to by everybody, reported in all the newspapers and followed by the people. Rallies and marches by organizations that supported him were huge, filling the sports stadiums in the cities and the main streets in small towns … Even his opponents felt the need to use the revolutionary vocabulary he had created … [T]here was no sense in any aspect of the public atmosphere that Sukarno was under threat of being deposed … By the morning of the next day, it had all disappeared.

Under the leadership of Soeharto, who was covertly backed by the United States, the Indonesian military coordinated a reign of terror across the last months of 1965 and on and on into 1968, collaborating with right-wing civilian militia to systematically murder somewhere between half a million and two million people. Eighty thousand people died in Australia’s playground, Bali, all killed by Soeharto’s military for being allied to the pro-Sukarno PKI, the Communist Party of Indonesia, or seeming to be. This party had grown as the secular, socialist branch of Sarekat Islam when that organisation split, and before 1 October 1965 had as many as three million members, with a further fifteen million connected to it through cognate organisations.

Though Australian educationists and other leaders lament that there is not more interest in Indonesia, Lane makes the important point that such uninterest is hardly surprising, given the political and cultural reality that flowed on from Soeharto’s displacement of Sukarno:

Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world … Yet today, and for the last fifty years, its international political presence has been almost zero. The primary reason for this is the 1965 counter-revolution in Indonesia and the consequent radical remaking-cum-unmaking of the nation. On the one hand, this counter-revolution produced an Indonesian state and economy that posed no threat to either Western or Japanese imperial economic or geopolitical interests, and on the other, a society whose new post-counter-revolutionary experience would emasculate any progressive politics for decades, and thus, also its intellectual and cultural life.

The first print run of Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind) – ten thousand copies – sold out in two weeks, and by the time the novel was formally banned, after nine months of informal suppression, it had sold a phenomenal 60,000 copies. The quartet continued to sell well in Indonesia and remains inspiring for Indonesian youth, within current political fermentations, though sales and distribution have been heavily curtailed by bans and state harassment.

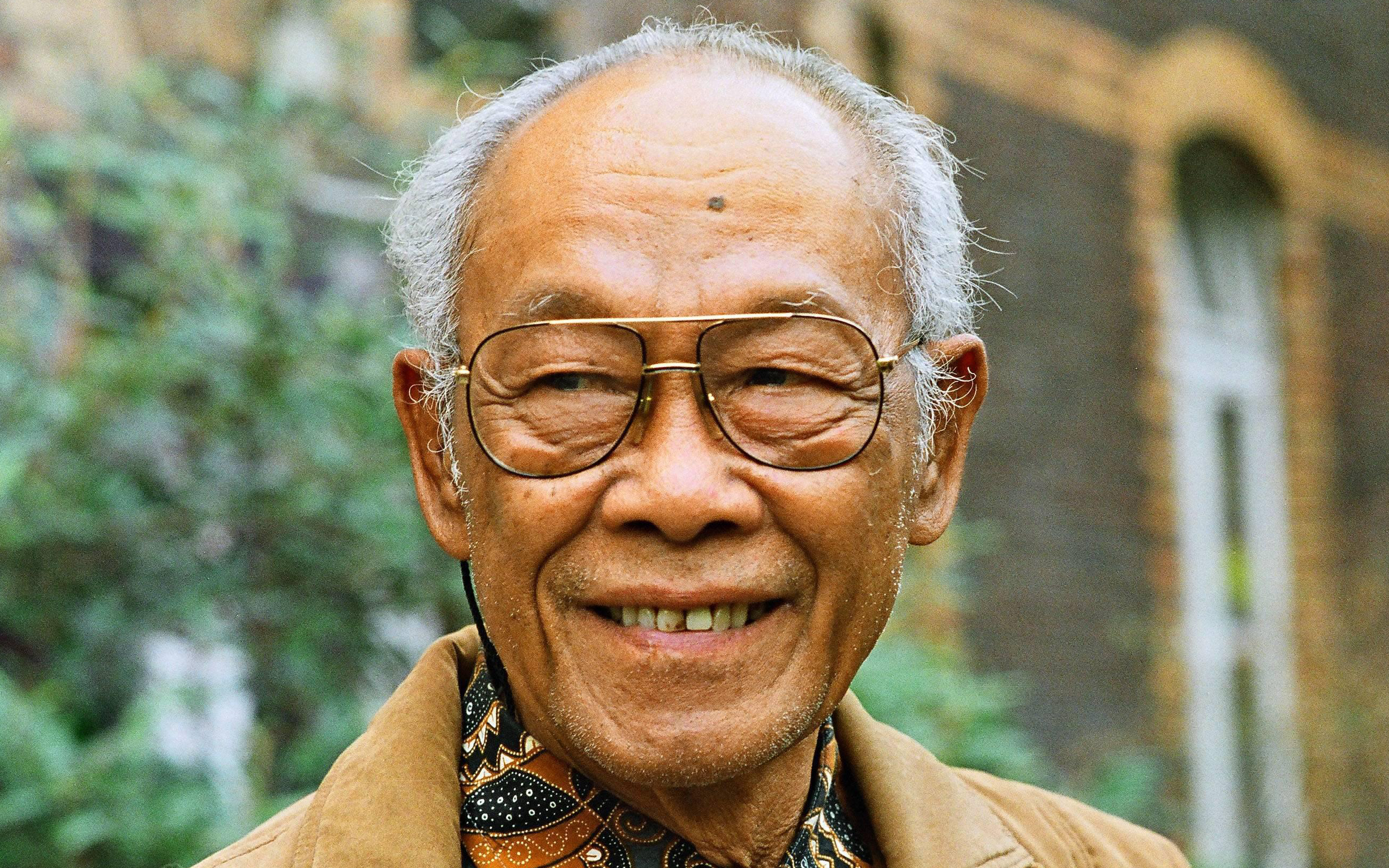

Pramoedya Ananta Toer, 1999 (Briggite Friedrich/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy)

Pramoedya Ananta Toer, 1999 (Briggite Friedrich/Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy)

Even after he was released from prison, Pramoedya was held under town arrest and not permitted to leave Jakarta until 1992. Weakened by his years in prison, he died in 2006 from heart disease and diabetes. Hasjim died in 1999, Joesoef in 2009.

Pramoedya, Hasjim and Joesoef were members of the Angkatan 45, Indonesia’s 1945 generation. (Adam Malik was too, in contrast to Soeharto, who, as a young man, had volunteered with the Dutch colonial army, the KNIL.) Like Sukarno, they thought that, after the overthrow of Dutch colonial rule and the expulsion of Dutch businesses in 1956–58, the revolution they had been part of needed to continue within Indonesian society itself. Wouldn’t Sukarno’s Trisakti ideal – of sovereignty in politics, standing on one’s own feet in economics and real character in culture – prove chimerical unless democratic institutions, such as the Sarekat Islam of Soerjo and Minke, guarded against the recreation and institutionalisation of autocratic power?

From our current historical vantage point, these fears appear well founded, not only for Indonesia but for all of those nations which had freed themselves from European colonisation at the end of World War II and formed themselves as a ‘Third World’. This term, coined by French anti-colonial anthropologist and historian Alfred Sauvy in 1952, referenced the Third Estate, of the 1789 French Revolution, and was intended to convey that a newly organised global majority would take possession of the dynamic of world affairs from the Western First and Soviet Second Worlds, as the people from outside the First Estate (the clergy) and the Second Estate (the aristocracy) had taken possession of national events in France. The Third World, as Vijay Prashad reminds us in his history of this initiative (The Darker Nations, 2007), was not a place. It was a project. ‘The great flaws in the national liberation project,’ Prashad suggests, ‘came from the assumption that political power could be centralized in the state, and the national liberation party should dominate the state, and that the people could be demobilized after their contribution to the liberation struggle … Once in power, the old social classes exerted themselves, either through the offices of the military or the victorious people’s party.’

According to the respected Indonesianist Harold Crouch, the Indonesian Communist Party ‘won widespread support not as a revolutionary party but as an organisation defending the interests of the poor within the existing system’. The ‘anti-PKI massacres’, as an analyst in the CIA’s Directorate of Intelligence wrote at the time, ‘rank as one of the worst mass murders of the twentieth century, along with the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders during the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s.’ Nonetheless, Australia’s leaders and intellectuals in 1965 for the most part cheered on what was happening in our closest international neighbour, ignored it, or in some cases, such as in Christopher Koch’s The Year of Living Dangerously (1978), implied that this mass extermination was the lesser of two evils (the greater evil being a Communist Indonesia).4

Australia also is caught up in the dynamics of the world that Pramoedya writes about, though we rarely hear or pay due credit to analysis advanced by writers and intellectuals from the international political and economic margins. Where Soeharto raced to take control of the mass media and its messages on 1 October 1965, in Australia such state control was and is not necessary. By and large, what we hear about why the centre is the centre and the margins are the margins is what the centre – now in the form of the United States – tells us. As a sub-imperial power, it suits us now to listen to the United States, its allies, and no one else.

If the Enlightenment dream of a just society is not faring well in Indonesia or throughout the former Third World, where cultural nationalism and religious and racial prejudice are stoked by leaders as a kind of balm for grotesque and growing inequality, new fundamentalisms of race, gender, and sexual identity seem also to be emerging here, as in the United States and the United Kingdom, and partly for the same reasons.

When Pramoedya, Hasjim, and Joesoef were released from prison, their children drove them around the new Jakarta so they could goggle at the city that had evolved while they were locked away. Joesoef recalled: ‘There were flashy buildings, many still under construction, very impressive. But I tried to explain to my children that they shouldn’t be too easily impressed. They should ask themselves, who owned these buildings? Who’s reaping all the profits from this development?’ Looking around our Australian cities, we might ask ourselves the same question.

This article is one of a series supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation.

Endnotes

- By convention, I use the shortened forms of ‘Pramoedya’, ‘Hasjim’ and ‘Joesoef’, rather than their full names, after the first reference to each.

- Max Lane, Indonesia Out of Exile: How Pramoedya’s Buru Quartet killed a dictatorship (Penguin Southeast Asia, 2022). Thank you to Professor Clinton Fernandes for reading and commenting on a draft.

- Soeharto retained the Dutch spelling of his name; Sukarno changed his from the Dutch ‘Soekarno’. See David Jenkins, Young Soeharto: The making of a soldier, 1921-1945 (Melbourne University Press, 2021), pp.xi–xiii.

- See Crouch, The Army and Politics in Indonesia, Cornell University Press, 1978, p.351; CIA analyst quote in Clinton Fernandes, Island Off the Coast of Asia: Instruments of statecraft in Australian foreign policy, Monash University Publishing, 2018, p.99; and on the Australian response to the 1965 violence, Scott Burchill, ‘Absolving the Dictator’, AQ: Journal of Contemporary Analysis 73: 3, May–June 2001.

Comments powered by CComment