- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: ‘Not like an arrow, but a boomerang’

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ‘Not like an arrow, but a boomerang’

- Article Subtitle: Ralph Ellison and literary humanism

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ralph Ellison could be abrasive. His biographer Arnold Rampersad records that James Baldwin thought Ellison ‘the angriest man he knew’. Shirley Hazzard observed that when Ellison was drinking he ‘could become obnoxious very quickly’. His friend Albert Murray recognised something in him that was ‘potentially violent, very violent. He was ready to take on people and use whatever street corner language they understood. He was ready to fight, to come to blows. You really didn’t want to mess with Ralph Ellison.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): James Ley on Ralph Ellison and literary humanism

The novel is constructed around a series of fights. In the first chapter, the Invisible Man wins his college place in a surreal contest, where young black men are pitted against one another in a wild free-for-all boxing match, then made to scramble for coins on an electrified floor for the amusement of the local grandees. His ill-fated outing with the college benefactor ends with a brawl in a seedy bar. When he moves to New York and finds a job in a paint factory, he gets into a physical altercation with his foreman. A scene where he addresses an angry crowd, trying and failing to prevent them from attacking the police over the unfair eviction of an elderly couple, leads to his recruitment by an activist organisation known as the Brotherhood, setting in train the novel’s final act, which culminates in a riot on the streets of Harlem.

Over the course of the novel, the Invisible Man becomes ever more adept at exploiting the ‘invisibility’ that comes with being viewed as a stereotype. He is initially drawn into unwanted confrontations because he tries to be agreeable. Misconstruing some shrewd advice handed down from his grandfather, he keeps his head down and does as he is told, only to find that meekness does not protect him. The intolerable conditions of his existence saw at the very bones of his identity. He makes his way through a postwar, pre-civil rights America conceptualised as a treacherous dreamlike space of symbols, psychological distortions, and uncertain expectations. Ellison conceived of his protagonist as ‘a man born into a tragic irrational situation who attempts to respond to it as through it were completely logical’. He characterised him as a ‘true Negro individualist’, who is psychologically a ‘traitor, to himself, to his people, and to democracy and his treachery lies in his submissiveness and opportunism’. The structural effacement of the Invisible Man’s individuality thus provides cover for his opportunism, even as it perpetuates his fury. ‘Somewhere beneath the load of emotion-freezing ice which my life had conditioned my brain to produce,’ he states, ‘a spot of black anger glowed and threw off a hot red light of such intensity that had Lord Kelvin known of its existence, he would have had to revise his measurements.’

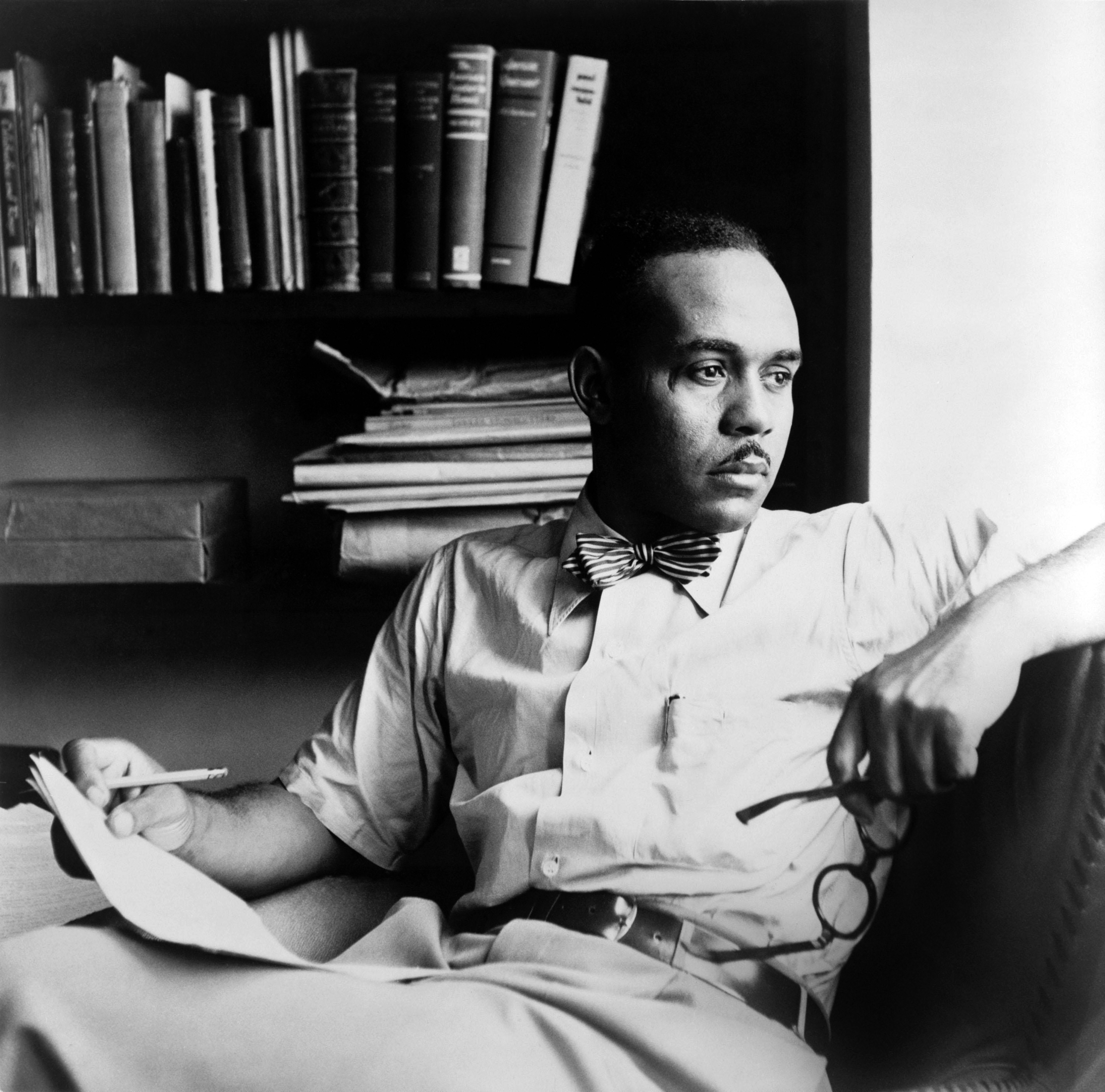

Ralph Ellison, 1950 (Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo)

Ralph Ellison, 1950 (Everett Collection Historical / Alamy Stock Photo)

When Ellison died in 1994, Saul Bellow recalled his old friend speaking of the ‘struggle to stare down the deadly and hypnotic temptation to interpret the world and all its devices in terms of race’. That struggle was, for Ellison, synonymous with the humanistic promise of literature itself. Like many writers swept up in the radicalism of the 1930s, he chafed at the Communist Party’s prescriptive attitude towards literature and eventually rejected its narrow instrumentalising aesthetics. He was anxious that Invisible Man not be interpreted merely as a novel of political protest. His intention, he said, was to illuminate ‘human universals’.

Invisible Man is Ellison’s audacious (and successful) attempt to write himself into the literary pantheon. It is a stylistic tour de force, openly indebted to the likes of Herman Melville and James Joyce. It is also a meditation on the doctrine of self-reliance set out by the American philosopher after whom Ellison was named: Ralph Waldo Emerson. The paradox of the Invisible Man is not simply that his inherited racial identity complicates his individualism, but that his very existence disturbs the promise of democratic humanism, demands a confrontation with his nation’s history and its founding ideological hypocrisies. His condition is at once invidious and inescapable. When a member of the Brotherhood asks in exasperation why ‘you fellows always talk in terms of race’, the Invisible Man fires back: ‘What other terms do you know?’

The literary imperative to grant characters their full measure of human complexity was, for Ellison, a democratic imperative. Stereotypical representations were not only artistic failures, but a form of representational disenfranchisement. The persistence of the ‘Negro stereotype’ in American literature, Ellison argued in an early essay, represented a refusal to accept the fundamental responsibility of a true democracy, which is to embrace in the fullest sense the idea of a collective of individuals. Such stereotypical depictions, he suggested, were a means of resolving the cognitive dissonance created by the evident conflict between the nation’s promise of equality and its historical betrayals of that promise. The black man is the physical manifestation of that bad conscience. The culture cannot acknowledge his full humanity because it would be an intolerable admission of guilt. When Mark Twain made the runaway slave Jim his representative of humanity in Huckleberry Finn (1884), observed Ellison, he laid bare the moral hypocrisy of an entire society.

The most brilliant aspect of Invisible Man is the way it negotiates the unresolvable tension between its protagonist’s symbolic and psychological implications. In recognising this as the underlying form of his ‘tragic irrational situation’, the novel exchanges the stereotypical for the archetypal. It presents the Invisible Man as a psychological conundrum: a literary descendant of the furiously contradictory narrator of Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864), whose essential characteristic Ellison saw as ‘ironic self-consciousness’.

Ellison was riled by the suggestion that Invisible Man was inspired by his old mentor Richard Wright, and specifically by Wright’s earlier and much slighter novella The Man Who Lived Underground (published posthumously in 2021, but known to Ellison in the 1940s), which also adopted the Dostoevskian metaphor of the ‘underground’ to signify its protagonist’s conflicted psychological state. As late as 1985, Ellison was pointing out, somewhat testily, the greater complexity of his creation. He insisted that he was drawing directly from Notes from Underground, adding (perhaps a little mischievously) that he had no need to seek inspiration in Wright’s fiction when he could draw on his personal knowledge of the man himself.

Ellison does not simply draw from Dostoevsky, he reconceptualises him. Notes from Underground satirises the ideological commitment of certain nineteenth-century Russian radicals to the contradictory notion of ‘rational egoism’. In doing so, the novel explodes the concept of individualism from within. The Invisible Man’s individuality is denied from without. The destabilising recursions of his ironic self-consciousness are a function of his social situation and its very real structural injustices. His ability to operate in what Ellison called ‘the vacuum created by white America in its failure to see Negroes as human’ makes him a fundamentally elusive character. He exists in this indeterminate space, suspended between his symbolic meaning and his psychological reality, a figure as inscrutable in his own way as Melville’s white whale. Once he understands the pernicious nature of his position, the Invisible Man uses this knowledge to navigate various tricky scenarios and evade determination, adapting to circumstances and assuming a variety of identities, with the result that we, as readers, can’t quite see him either. In a perverse way, he embodies the nation’s ideology of self-invention, his personality becoming legible only as a reflection of its hypocrisies.

There are numerous references to betrayal in the novel, most of them assuming that the Invisible Man owes his loyalty to his race. ‘Instead of uplifting the race,’ the college president admonishes him, ‘you’ve torn it down.’ A separatist rabble-rouser named Ras accuses him of ‘betraying the black people’. His subversive grandfather states, somewhat ambiguously: ‘Our life is a war and I have been a traitor all my born days, a spy in the enemy’s country.’ But it is never entirely clear to the Invisible Man, who is betrayed before he learns to betray, where loyalty is owed. How and why should one remain loyal to an unstable identity that is a product of an unwelcome history and manifests as an infinite regression? The Invisible Man describes himself in the novel’s opening lines as a ‘spook’ – a multivalent word with racist connotations, reclaimed by Ellison to suggest both the unreality and haunting inevitability of such categorisations.

Martin Luther King Jr famously said that the arc of history bends toward justice. The Invisible Man proposes, rather more darkly, that the world moves ‘not like an arrow, but a boomerang’. He becomes suspicious of the Brotherhood’s attempts to press him into service and the smug certainties of its official ‘scientific’ theories of historical progress, which are contradicted by the advice of one member who tells him to ‘act first, theorise later’. In choosing the solitary path of evasiveness, the Invisible Man ultimately gravitates towards contemplation rather than action. At the end of the novel, he retreats to the ‘underground’, where he can ‘try to think things out in peace, or, if not in peace, in quiet’.

This murkily ambivalent quality perhaps goes some way to explaining why Ellison’s reputation has been eclipsed to a significant degree by James Baldwin and Toni Morrison, whose work has proved more amenable to the assertive cultural politics of the post-civil rights era. A singular and gruff figure, Ellison remained committed to a universalising version of literary humanism that has come to seem dated. At one point, in a passage reflecting on the meaning of that elusive word ‘human’, the Invisible Man recalls his old English professor riffing on some well-known lines from Joyce:

Our task is that of making ourselves as individuals. The conscience of a race is the gift of individuals who see, evaluate, record … We create the race by creating ourselves and then to our great astonishment we will have created something far more important: We will have created a culture. Why waste time creating a conscience for something that doesn’t exist? For, you see, blood and skin do not think!

The reasoning and vocabulary are paradoxical, inescapably so, and Invisible Man develops a complicated understanding of those paradoxes. Yet the novel retains an allegiance to literature’s generative possibilities, intellectual imperatives, and resistance to political co-option. It does not propose that, as one character impossibly suggests, one might step ‘outside history’, but it does gesture beyond history’s pernicious categorisations. ‘For the first time,’ the Invisible Man reflects, ‘I could glimpse the possibility of being more than a member of a race. It was no dream, the possibility existed.’

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment