- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Refusing silence

- Article Subtitle: Reiterations of violence in Tony Birch’s new novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

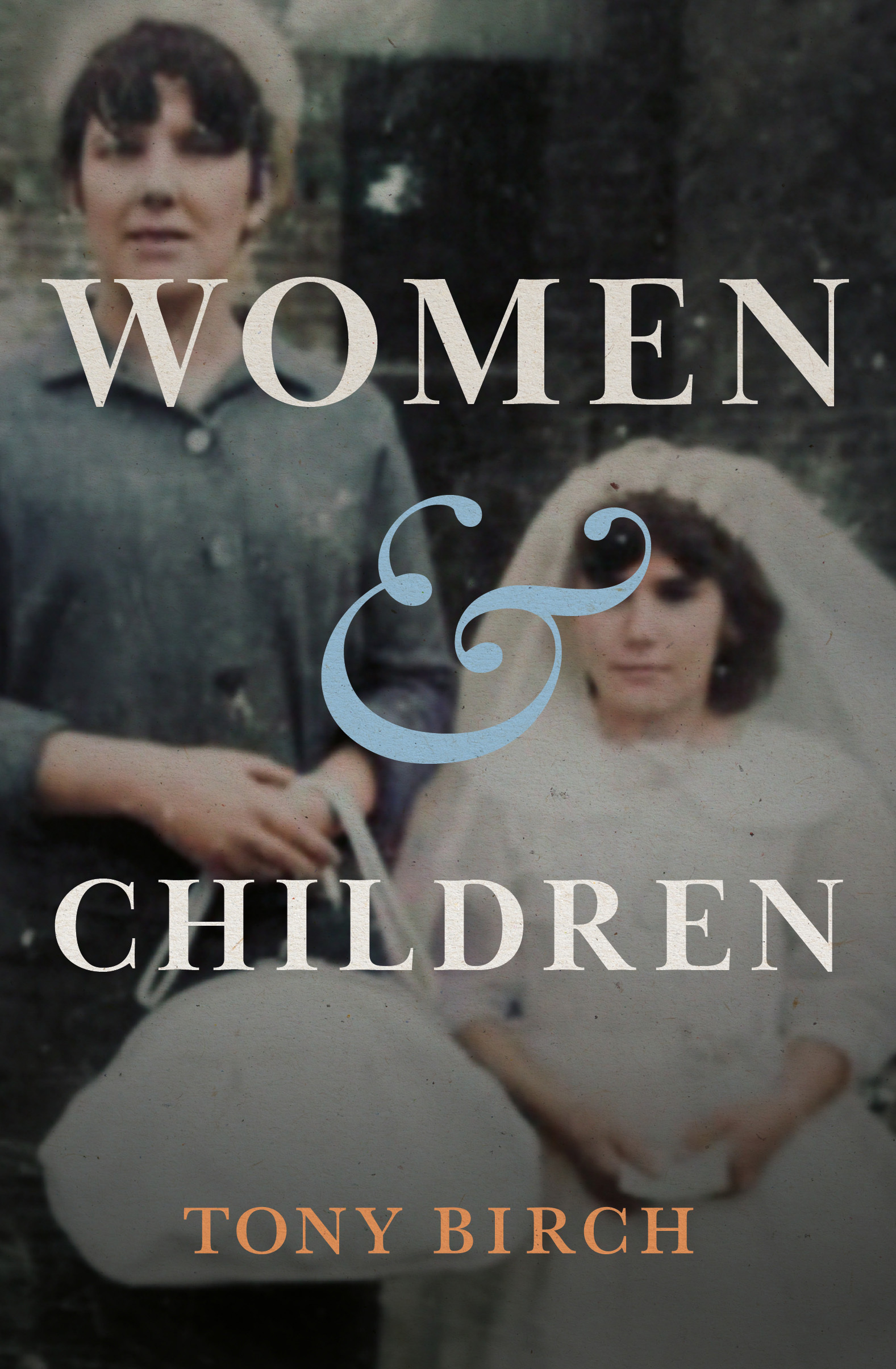

In conversation with the Guardian’s Paul Daley in the final days of 2021, Tony Birch addressed the recurring presence of both strong women and violent men in his work. Citing the Sydney writer Ross Gibson, Birch said he likes to think of the common themes that a writer revisits across his or her body of work as ‘reiterations’. In Birch’s oeuvre, perhaps chief among these reiterations is the impact of male violence on family and community life – from ‘The Butcher’s Wife’ in Shadowboxing (2006) to the Kane men in The White Girl (2019). His latest book, Women and Children, brings this theme into sharp relief.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Naama Grey-Smith reviews 'Women and Children' by Tony Birch

- Book 1 Title: Women & Children

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $34.99 hb, 328 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

While Joe’s point of view is often centred, the third-person narration encompasses all family members, as well as grandfather Charlie’s friend, the ‘scrap metal king’ Ranji Khan. Charlie and Ranji are, like Jack Haines in The White Girl or Brixey and Rory in Ghost River (2015), examples of another kind of man we meet in Birch’s fiction. These decent, humble men, who, while flawed, do their best to care for others, are affectionately drawn characters that win the reader’s heart. Conversely, we spend no time at all inside the violent mind of Ray Lomax, Oona’s boyfriend. This is not a sacrifice of complexity; Birch’s characters, whether endearing or repugnant, are consistently convincing. Rather, it seems to reflect a choice to honour that which nourishes. Birch writes in his author’s note: ‘I want to remind my brothers that we were once children and not damaged men.’

The shifts in point of view, while not always smooth, enable a story that is larger than one character. As the narrative progresses, Marion’s and Oona’s perspectives, and their deep sisterly bonds of love and loyalty, take up increasing space. This goes hand in hand with the women’s growing agency in response to the silence and complicity with which their pleas for help are met. Ruby, too, develops a fierceness that Joe admires.

While the book’s cover features a photo of Birch’s sister and godmother, taken by his mother, Birch clarifies in his author’s note that this fictional story ‘is not the story of my own family, but a story motivated by our family’s refusal to accept silence as an option in our lives’.

Silence is a constant thread in the novel, and a reiteration across Birch’s body of work. In Ghost River, ‘silence was a valued lesson … keep the mouth shut and lay doggo’. Women and Children similarly offers a parable, told by Charlie, about a dog that ‘kept his mouth shut’ – an innocent Jack Russell that was put down for the crimes of another dog, but told nothing to the police and so ‘died a hero’. Joe soon learns that in ‘a neighbourhood where blindness was a skill’, when you see bruises you ‘never ask … not about bodies’. The contradiction between valorised silence and the imperative to help those you love defines this story.

Though seemingly innocuous, ‘women and children’ is a layered and even loaded phrase. For those of us with a biblical education, it evokes the Old Testament, where it often conveys indiscriminate bloodshed (as in ‘put to the sword those living there, including the women and children’, Judges 21:10). The phrase is usually juxtaposed with ‘men’, or else coupled with types of property and plunder alongside ‘herds, flocks and goods’ (Numbers 31:9). Meanwhile, in a community services context, ‘women and children’ is associated with family and domestic violence supports. The phrase also has a maritime history, with supposed Victorian ideals of masculine chivalry encapsulated in the notion of evacuating ‘women and children first’ (known as the Birkenhead drill). Reiterations, then: ownership, violence, protection.

It is in response to violence in Women and Children that caring for others becomes a defiant form of resistance. The novel delivers a poignant indictment of racism through ‘the moneybox boy’ – a metal box at Joe’s Catholic school that is shaped as a ‘black-faced child’ who swallows coins ‘in support of “the poor coloured children of the missions”’. Joe, who has a dark birthmark on one cheek, feels affinity with the much-abused ‘moneybox boy’. He paints his own face black in solidarity and is severely punished by the nuns. His connection with the metal boy endures, and is a moving storyline.

Like the characters that inhabit Women and Children, Birch is a natural storyteller who makes every element work for him: plot and pace, character and dialogue, scene and setting. Across Birch’s prolific output, including this latest offering, what stands out is how unhindered his language feels, how unaffected. Here is a writer who is not afraid of his words – one who would rather have stories where before there was only silence.

Comments powered by CComment