- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

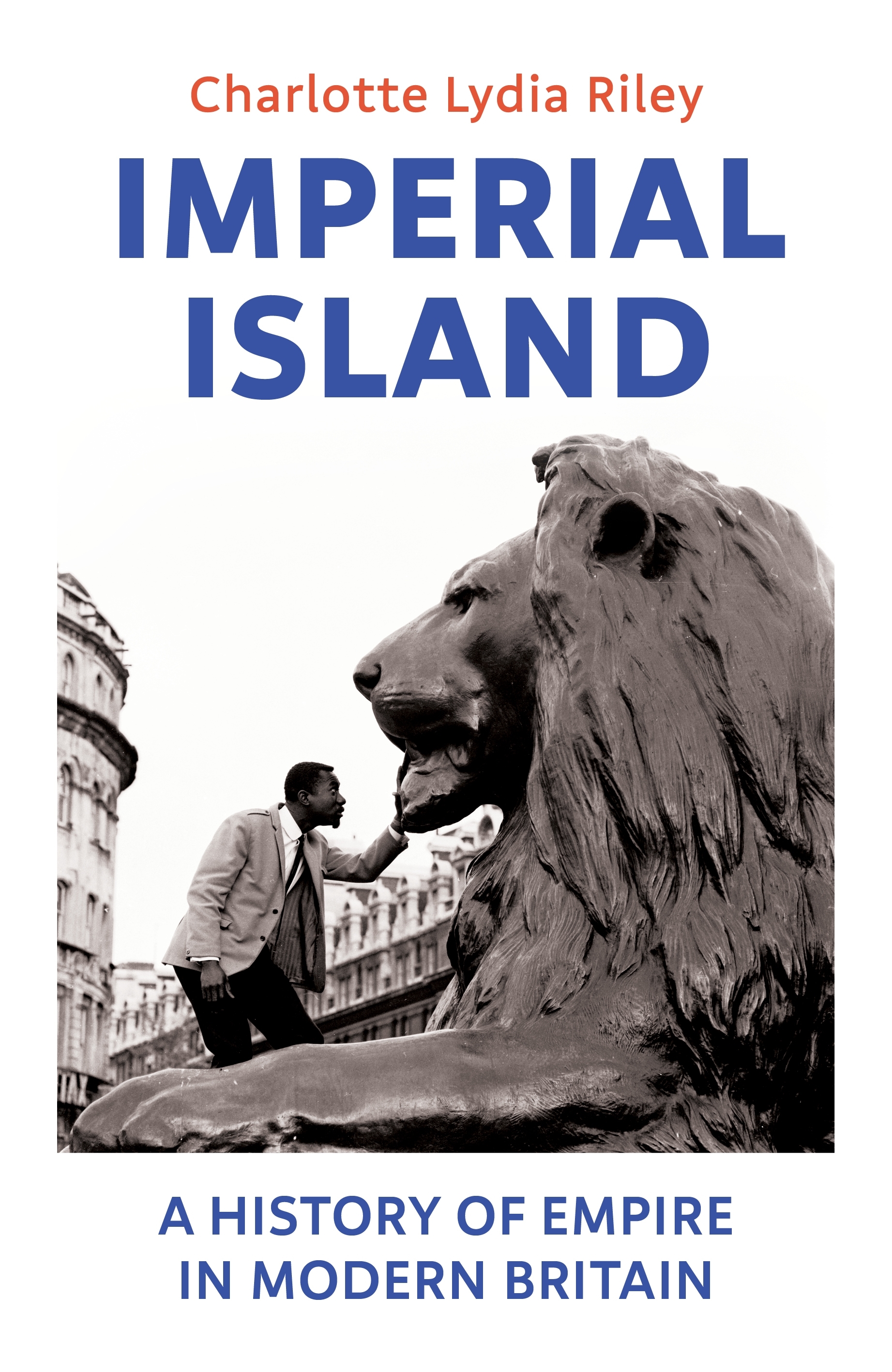

- Article Title: Antipodean echoes

- Article Subtitle: Empire’s postwar strains

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The opinions of Kandiah Kamalesvaran AM, better known by his stage name Kamahl, on the proposed Indigenous Voice to Parliament received extensive media attention in September 2023. A household name for many Australians, the Malaysian-born crooner’s indecision frustrated both the Yes and No camps.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jon Piccini reviews 'Imperial Island: A history of empire in modern Britain' by Charlotte Lydia Riley

- Book 1 Title: Imperial Island

- Book 1 Subtitle: A history of empire in modern Britain

- Book 1 Biblio: Bodley Head, $35 pb, 384 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.readings.com.au/product/9781529923803/imperial-island--charlotte-lydia-riley--2024--9781529923803

Charlotte Lydia Riley’s Imperial Island does not tell Kamahl’s story, but it does present the bigger framework within which his and countless other (post)imperial lives were lived. A lecturer at the University of Southampton and an avid user of the social media platform formerly known as Twitter, Riley is a prominent combatant in Britain’s most recent history war. Imperial Island asks, among other questions, how Britain’s colonial past became such a fraught topic. Riley’s answer is that empire has always been fraught. A helpful bibliographical chapter enumerates Imperial Island’s debt to a range of authors who in the past decade have challenged views of Britain’s empire as either the lynchpin of a proud history or a distraction from the ‘real’ stuff of conflict and change within the nation state. Kojo Karam’s observation in Uncommon Wealth (2022) that the empire made Britain, not the other way around, and the careful piecing together of metropolitan anti-imperialism in Priyamvada Gopal’s Insurgent Empire (2019), are but two of the works Riley credits as foundational to her own.

This is not to say that Imperial Island is derivative. Far from it. Particularly distinctive about Riley’s work is her attention to the ordinariness of empire, the way that it shaped the lives of British citizens and subjects in unexpected ways. Drawing on the dutiful reports of the Mass Observation project alongside Gallup polls, newsreel footage, private letters, agitational leaflets, guidebooks for new migrants, and a welter of pop cultural productions, from children’s books to punk rock, she offers readers a distinctive, bottom-up view of how Britons old and ‘new’ accommodated to the end (or perhaps transformation) of empire.

Modern Britain for Riley begins with World War II, when ‘the empire was arguably more mobilised, more centralised and more British than ever before’. That Britain’s capacity to ‘stand alone’ against Hitler relied on countless millions of colonial subjects is far from unknown. Riley’s first chapter tells a different story: how this global imperial effort coloured popular perspectives on empire. One respondent to a Mass Observation survey in 1942 remarked that while the empire ‘has been a great achievement … somehow I think its day is over’.

These voices of anonymous Britons pepper Riley’s account, but hers is no myopic view from the imperial centre. The wartime service of Indian, Māori, Caribbean, and African subjects is detailed, as is the struggle of people of colour who had long resided in the metropole. The League of Coloured Peoples 1944 Charter articulated clearly the need to end ‘racist discrimination and the colour bar at home [and] colonial exploitation overseas’ and tried to support children born of African-American GIs and white women.

At war’s end, the Colonial Office had ‘little sense’ that decolonisation was imminent. A Pathé production informed Britons that Indian independence in 1947 was not a loss: the mother country had ‘fulfilled her mission’, and the new nation would become an equal member of the Commonwealth. The so-called Windrush Generation were greeted officially as Commonwealth citizens with equal rights whose contribution to the motherland’s economic recovery was highly valued, even as resentment festered and exploded in race riots in the late 1950s, while millions of white Britons went the other way, to the settler Dominions and Africa in particular.

These white settlers sometimes found themselves on the front line of violent conflicts labelled ‘emergencies’, in Malaya and Kenya. These were not distant conflicts for those in the metropole: many heard from family members on colonial deployment, or via voluminous news commentary. One man wrote to his local MP that news of torture and the use of concentration camps made ‘a considerable number of Englishmen … feel actually ashamed of their nationality’. Empire’s crimes, far from the recent discovery of woke activists, have long been a source of deep moral concern.

Riley shows how the end of empire ‘came home’ to Britain in the 1960s. Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, warning that coloured migration was undermining Britain’s social fabric, is well known. Less so is the work of migrant communities, from Claudia Jones’s West Indian Gazette to the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination, which exposed racist landlords and publicans and challenged the ‘Whites first’ policy of trade unions and employers making use, and eventually expanding the reach, of nascent anti-discrimination laws. Riley shows that this – today castigated as ‘cancel culture’ – has long been the bread and butter of anti-racist activism.

By the 1980s, memories of empire had drifted into nostalgia. Tub-thumping over the Falklands War of 1982 showed how ‘imperial culture continued to suffuse British society long after many people had stopped thinking consciously about empires at all’, while the celebrity activism of Live Aid, and its later incarnation as Artists Against Apartheid, not only replicated forms of imperial humanitarianism, but also worked to whitewash Britain’s role in fostering global inequality. In a final chapter, Riley brings her narrative up to the present day, locating the ongoing ramifications of empire both at the level of policy – from the ‘Hostile Environment’ to revelations about colonial records that were ‘migrated’ to Britain at independence – and the everyday experiences of marginalised communities during the ‘War on Terror’.

Kamahl last made news in 2021, when he went public about the racist treatment he was subjected to on the television variety program Hey Hey It’s Saturday. In one instance, the performer had white powder thrown in his face, to which host Darryl Somers’s off-camera sidekick John Blackman responded: ‘You’re a real white man now Kamahl, you know that?’ For the formerly colonised, empire’s injuries are far from over.

Australia occupies a small part in Riley’s narrative, yet her powerful perspective on Britain’s end of empire offers much to inform our own. Imperial Island’s stretching of the narrative of decolonisation to the present will be no surprise to Indigenous peoples, whose experience of dispossession is, to paraphrase a hashtag popularised by First Nations scholar Chelsea Watego, just another day in the colony. To critics who accuse her of ‘rewriting history’ – a preposterous accusation, given that is precisely the historian’s craft – Riley responds: ‘For as long as Britain is committed to a version of history that doesn’t tell the whole truth, it will be a nation trapped in its past.’ A statement which, to put it lightly, has quite the antipodean echo.

Comments powered by CComment