- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: A maddening country

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A maddening country

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Why did Australia vote against the Voice referendum?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joel Deane on the long political shadow of John Howard

But it’s too easy to blame everything on the fourth estate.

Don’t get me wrong. Yes, I was appalled by the media’s coverage of the referendum campaign, as well as by its response to the referendum result. Yes, some takes were hysterical. Yes, many commentators produced more smoke than light. Yes, most analysis lacked perspective. And yes, the media’s systemic failure to inform is one of the major reasons why Australia struggles to properly debate everything from climate change to the pandemic to tax reform to nuclear submarines to Reconciliation.

But that cannot be the only reason why, collectively, we chose to vote No and to remain captive to our colonial history. There were other factors in play – namely, racism, the lack of bipartisan support for the Voice, the splitting of the Yes campaign into two camps, and the interventions of Senators Lidia Thorpe, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, and Pauline Hanson.

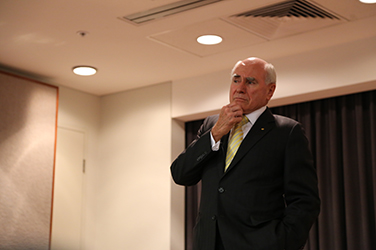

Fundamentally, though, I believe that John Howard is the main reason why more than sixty per cent of voters said No. Let me explain why Howard deserves the credit for this national disgrace. The leaders of dead governments are like Hamlet’s Ghost. They tend to linger in the wings of the national stage, alert to any opportunity to free themselves from post-political purgatory. That’s why Scott Morrison recently donned a Kevlar vest to tour Hamas attack sites in Israel. That’s why Malcolm Turnbull keeps campaigning against Rupert Murdoch. That’s why Tony Abbott – newly appointed to the board of Fox Corporation by Lachlan Murdoch – keeps nattering about climate change. And that’s why Kevin Rudd reinvented himself as Australia’s chief diplomat in the United States. The fact that Julia Gillard escaped this karmic afterlife suggests she’s made of sterner stuff than her alpha-male contemporaries. As for Howard and Paul Keating, the patriarchs of the Liberal and Labor clans: they reside on different planes.

John Howard, 2011 (Gary Doak/Alamy)

John Howard, 2011 (Gary Doak/Alamy)

Keating – as demonstrated by his recent eulogy for former Labor leader Bill Hayden and his intemperate attacks on Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and Foreign Affairs Minister Penny Wong – remains an agitator for reformist, nationalist government. Howard, by comparison, seems content to spend his political afterlife watching Test cricket because, although he lost government in 2007 and saw his Rosebud (WorkChoices) consigned to the flames, he knows Australia remains in his political shadow. After all, the Australia we now live in – a maddening country of haves and have nots, winners and losers, us and them – is the product of Howard’s decades-long efforts to turn Australia into a Neighbours-style remake of Margaret Thatcher’s United Kingdom.

You need to go back to 2001 to understand how Howard remade Australia. At the beginning of that year, Howard seemed headed for defeat at the federal election. The economy had gone backwards with the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax, One Nation’s Pauline Hanson was gearing up for a return to Canberra, voter satisfaction with Howard had sunk to forty per cent, and, among Labor brethren, Kim Beazley was spoken of, sotto voce, as a PM-in-waiting.

What happened next changed Australian politics. Howard used the 2001 budget to buy his way back into contention. Then – before and after the 9/11 terrorist attacks – he hit the jackpot with his opportunistic decision to treat the arrival of refugees on boats as a security threat rather than as a humanitarian crisis, miraculously delivering a 3.4 per cent swing to the Coalition at the November election.

Needless to say, Federal Labor was destroyed. In fact, the aftershocks of 2001 still rattle in some Labor circles. One reason why Howard still reverberates is that the Rudd–Gillard–Rudd governments (2007–13) lacked the unity to stay in power long enough to reset the lingua franca of campaigning and governing and to expunge Howard. The 2013 election of Abbott – a man who once described himself as the political love child of Howard and Bronwyn Bishop – extended the afterlife of the former Member for Bennelong. Then we had Bill Shorten, who tried (and failed) to end the Howard era with a crash-or-crash-through policy platform.

Next came Albanese, who took a different tack. In opposition, Albanese ran a small-target campaign. In government, he has focused on administrative competence, repairing fences with China and Australia’s Pacific neighbours, and rubber-stamping Morrison-era policies – the stage three tax cuts and AUKUS deal – that will define Australia domestically and internationally for at least the next decade.

Albanese is playing for time – planning to outlast Howard’s ghost by emulating Bob Hawke and governing for at least three election cycles. In the meantime, he has been planning to differentiate Labor by adopting first-term reforms – such as the National Anti-Corruption Commission and the Voice – that are high on symbolism and, in terms of recurrent expenditure, low on cost. The disastrous referendum result – backed by fewer than four-in-ten voters and zero states – puts those short-term plans in jeopardy and brings Dutton back into electoral contention.

Albanese grossly underestimated the opponents of the Voice, much as former British PM David Cameron underestimated the proponents of Brexit. In hindsight, Albanese’s promise to hold the Voice referendum during his first term was a Rudd-like mistake – more about the idea than the implementation. A more strategic approach would have been, in the immediate aftermath of the 2022 election, to prepare the ground for a decade-long path to Reconciliation and Treaty by legislating a Voice to parliament – knowing a future Coalition government would find it difficult to kill off a legislated Voice with a Teal- and Green-dominated Senate. With the referendum defeated, however, a legislated Voice is now impossible and, according to Indigenous academic Marcia Langton, Reconciliation is dead.

I hope Langton is wrong. I hope the Reconciliation and Treaty efforts of Victoria and South Australia create new precedents for federal political action. But the political realist in me worries that the failure of the Voice referendum is a major setback for Indigenous self-determination.

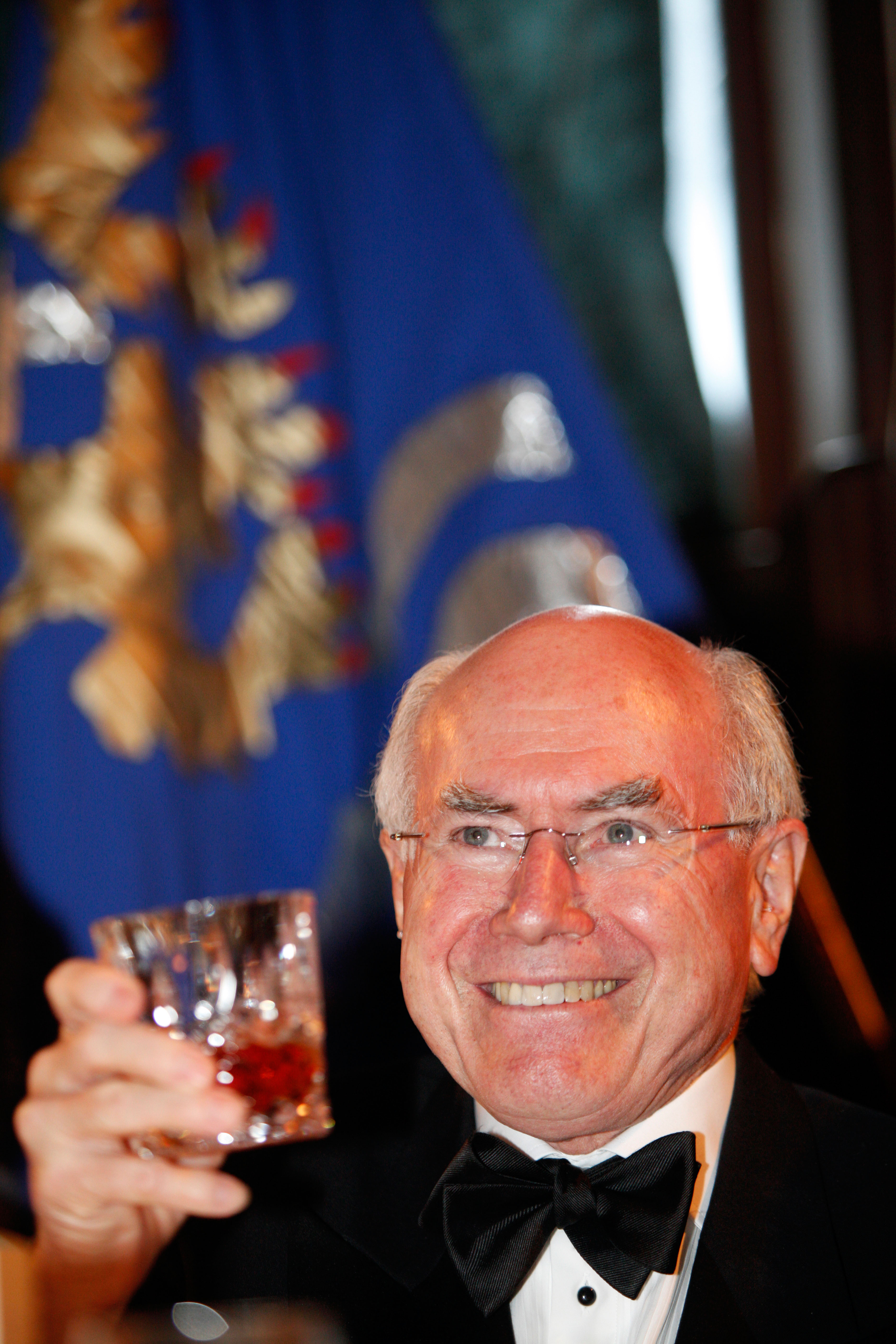

Lidia Thorpe, 2022 (Leo Bild/Alamy Live News)

Lidia Thorpe, 2022 (Leo Bild/Alamy Live News)

Not only that. Albanese has needlessly surrendered the political momentum. Over summer and throughout 2024, Dutton will attempt to take control of the national agenda and define the narrative of the next federal election campaign – attacking Albanese’s broken promise to relieve cost-of-living pressures and using the conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza to stoke national security fears. Of course, Albanese has the power of government at his disposal and should be able to wrest back momentum and reset the political agenda. But – as John Howard showed in 2001 – none of this will matter if Australia finds itself on the wrong side of a wild-card event such as the re-election of Trump or the escalation of wars in Ukraine or Gaza.

Anything is possible now.

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment