- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: All class

- Article Subtitle: A life of Toynbean resolve

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

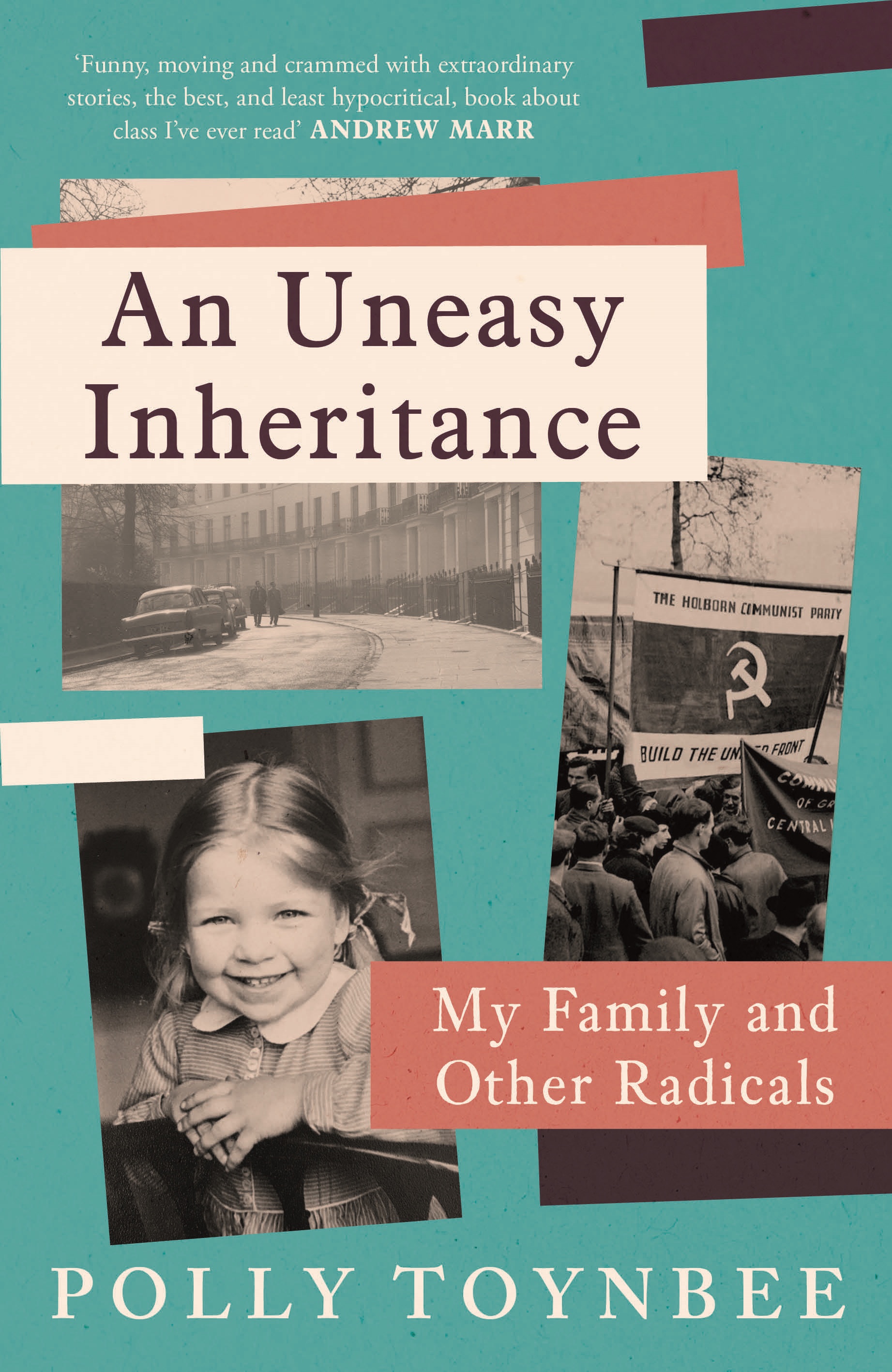

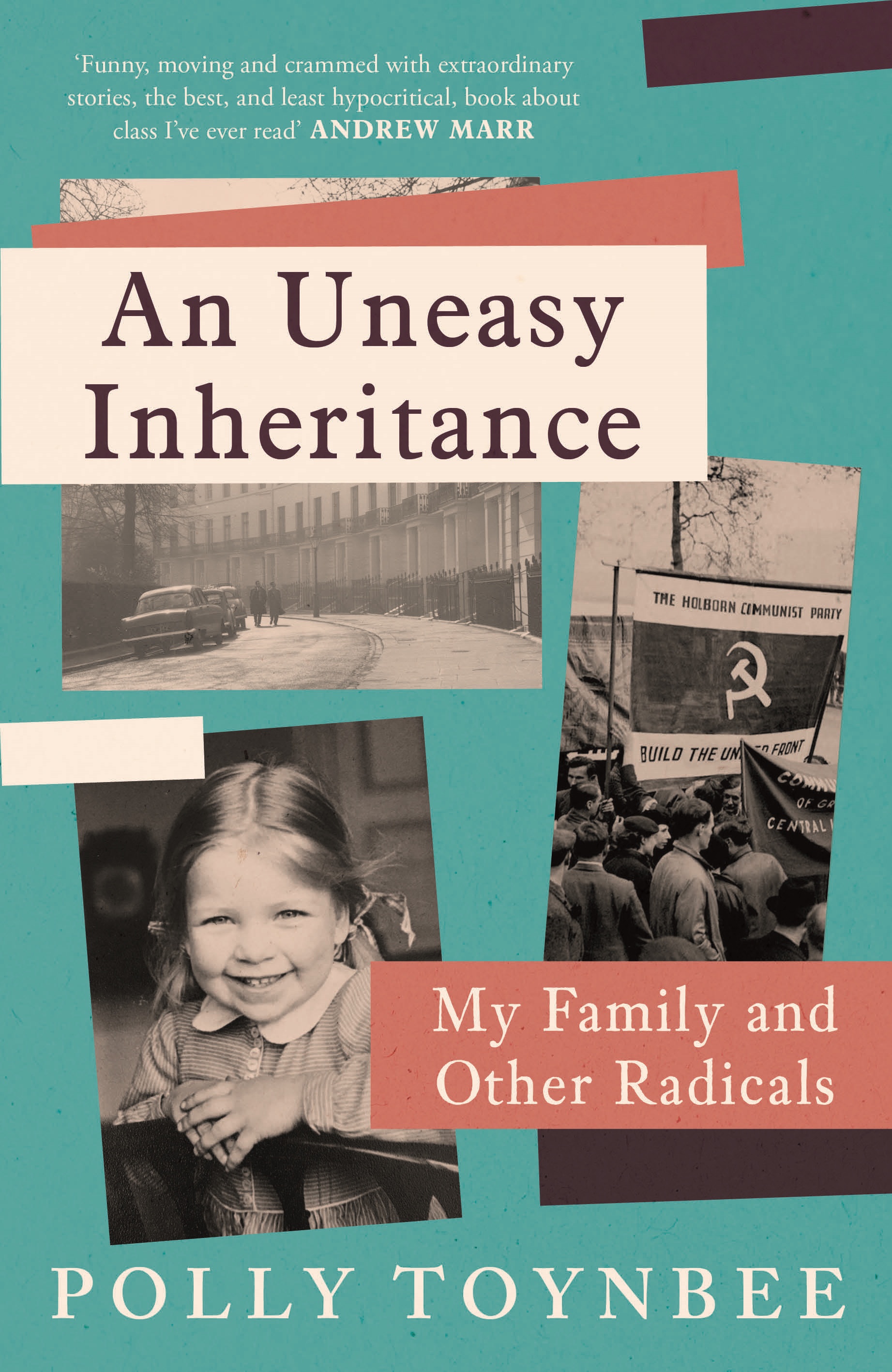

As one of Britain’s most indefatigable and widely read left-wing columnists, Polly Toynbee has weathered the ire of the right for over fifty years. In fact, controversy has never seemed to bother her. She has never felt the need to justify herself, and every chant of ‘champagne socialist’ has seemed only to deepen her resolve to champion causes of the disadvantaged.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): James Antoniou reviews 'An Uneasy Inheritance: My family and other radicals' by Polly Toynbee

- Book 1 Title: An Uneasy Inheritance

- Book 1 Subtitle: My family and other radicals

- Book 1 Biblio: Atlantic, $45 hb, 448 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Steeped in a Fabian tradition which aims to combine intellectual rigour with realism, by the piecemeal standards of her own Labour Party she certainly is radical: vociferously anti-establishment, anti-monarchy, anti-Oxbridge. She rejects the neoliberal shibboleth that success should be measured solely by GDP growth. She despairs over Britain’s yawning inequality and insists on egalitarianism as the ultimate gauge of a society’s health. Most of all, she laments that while socioeconomic status is the biggest predictor of life chances, class has all but vanished from mainstream discourse.

Such arguments may prove compelling in a debate, but are hardly going to set a memoir on fire, especially not when delivered in the stolid prose style of Toynbee’s columns. She is a skilled rhetorician in the press and on television, but however insightful her points, her mind never strays too far beyond the doctrinaire. It’s the kind of mind you need as a lifelong, tribal political creature; the kind that can make literature deadeningly dull.

Refreshingly, this memoir isn’t stultifying at all. Toynbee’s storied left-wing family is fascinating and contradictory. In the book’s best chapters, there are vivid and often affecting accounts of a family stretching their ‘moral means’ to extreme and sometimes tragicomic limits.

Take her father, Philip, a novelist and communist. In a chapter that sounds like a cross between Tartuffe and Uncle Vanya, Toynbee describes how he converted to Christianity late in life and then converted his house into a Christian commune, in part to stave off his depression. The results were predictably disastrous, wrecking his youngest daughter Clara’s adolescence and alienating much of the family. A charismatic young priest called John eventually infiltrated the commune and attempted to start a cult. (John was later jailed for the manslaughter of a young woman he was ‘exorcising’.)

The chapter on her sister Josephine’s travails, as she lurched from husband to husband and country to country in pursuit of utopian ideals, is no less cautionary. ‘I felt pallid beside her,’ Toynbee writes. ‘She simply refused to follow the map, as she struggled, sometimes comically, to free herself from the guilt of our English privilege.’

You wonder at times if the story is as reducible to class dynamics as Toynbee believes. Yet she is a sensitive narrator, and beneath her opinions you sense the novelist she could have been and once wanted to be. Lacking the egotism to prevail as an artist, she gave up her literary dreams early in favour of unglamorous, self-denying activism and journalism. What is clear is that, unlike Josephine, Polly is not utopian and has applied steadfast ideals to better effect.

In 1966, she worked in war-torn southern Rhodesia for Amnesty International, against the white Rhodesians. She remembers them as ‘boorish, bigoted and arrogant, [without] that old colonialist pretence of a little noblesse oblige towards Africans’. She was quickly deported from the country. She enrolled at Oxford but felt ‘a fundamental distaste’ for the place, for ‘all its ways, its conceits and arrogances, its denizens’ obnoxious certainty of their superior merit’. She then dropped out and breezed into column writing. Discontented with that ivory tower, she tried out reportage. In one intrepid episode, she accepted a range of menial jobs, including a role on the production line at Tate & Lyle, and published a book about the experience, A Working Life (1971). Later, she wrote Hard Work (2003), a similar book about her time living on the minimum wage in a Clapham council estate:

Once you cross the threshold from middle class work to manual drudge, you pass through a green baize door [into a] world of unimportant, uninteresting non-personhood. Do you smile and say hello to your street sweeper? I do now. He may think I’m patronizing Lady Bountiful but it makes me feel better not to walk past without acknowledging his work.

This passage is illustrative of the memoir. Toynbee has the insight to realise how she may come across and is nearly paralysed by that insight, but she has never quite transcended her patrician, toffee-nosed tone. She is someone who does not like being middle class but is so, incorrigibly – a ‘posh left-winger’, as she puts it, who has embarked on ‘an easeful life of well-paid London journalism, instead of doing good’.

If she never learns to talk to working-class people as equals, that is without being hyper-conscious of class difference (or as she might put it, their ‘non-personhood’), what rescues Toynbee is that she is as tough on herself as her worst enemies, and wrestles constantly with the irreconcilability of her background and ethics.

Detractors have accused her of moral vanity, but a more profound sociological and moral curiosity about other people’s lives is at work. Her ultimate argument that the fine gradations of class are still with us, and that we are slowly, lamentably losing the language for them, is after all a salient one. Toynbee’s politics will not save the world, but if Britain’s ruling classes were as sober and principled as her, that country would surely be in far better shape.

Comments powered by CComment