- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

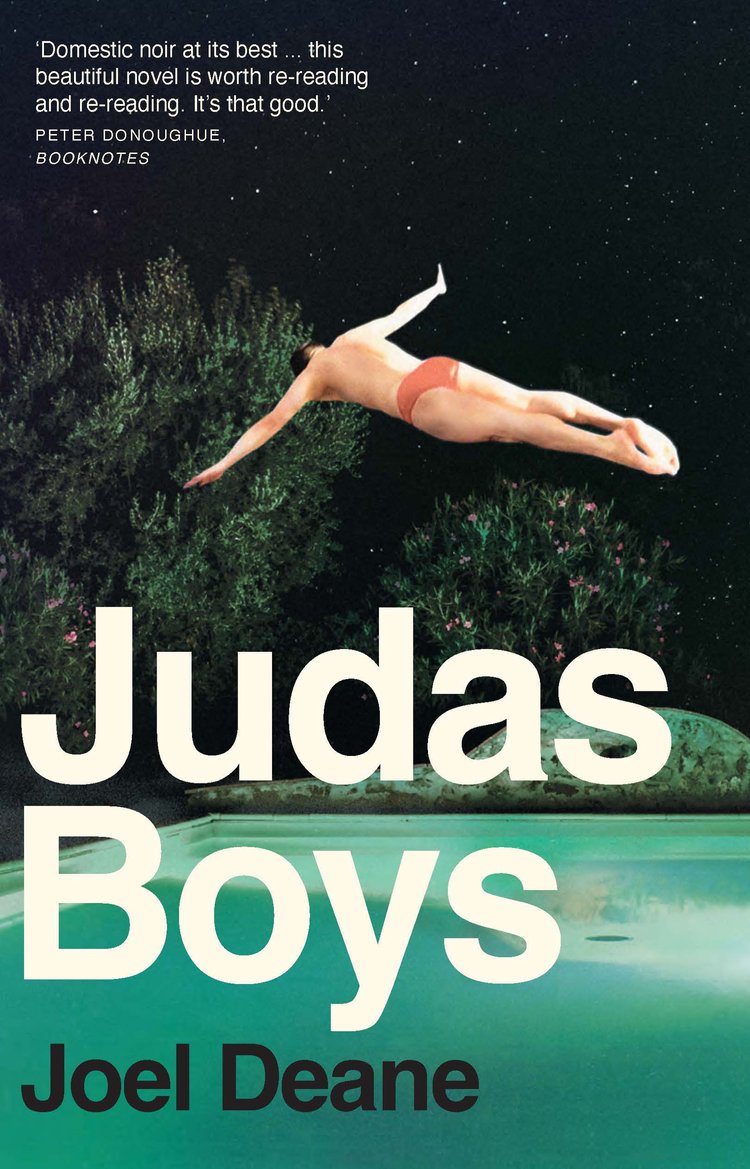

- Article Title: Falling into a dream

- Article Subtitle: Joel Deane’s visceral novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Early in Joel Deane’s third novel, the point of view shifts from the first to the third person as the narrator, Patrick ‘Pin’ Pinnock, reflects on a moment in boyhood, standing atop a diving board at night.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Anders Villani reviews 'Judas Boys' by Joel Deane

- Book 1 Title: Judas Boys

- Book 1 Biblio: Hunter, $27.95 pb, 229 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Pin’s life is in free fall. In Canberra, sexual misconduct allegations – hinted at, and likely true – have seen him removed from his role as the press secretary for Benedict Cox, the ‘Assistant Minister for Regional Tourism’ and a fellow ‘Judas Boy’, a former student of St Jude’s Christian Brothers school. Depression has him showering fully clothed, lying down. ‘A bearded vagabond’, he returns to Melbourne, taken in by Jill and Anna, his ex-wife and trans daughter whom five years earlier he abandoned without explanation. The novel alternates between Pin’s abject experiences in Melbourne and examining the source of his torment: his sense of culpability for the tragic fate of his friend David ‘OB’ O’Brien, another Judas boy.

Deane is no stranger to creating violent, misogynistic, dishonest, disloyal male characters. The Norseman’s Song (2010), his second novel, is narrated by two men: a taxi-driving ex-prisoner who, in one scene, places a prostitute in a headlock; and a Norwegian whaleman who murders people as ‘God’s blood angel’. Within these men, including Pin, lies the belief that they are irredeemable. Their shocking actions reveal a desire to vindicate this belief. Judas, whom Deane also invokes in The Norseman’s Song, becomes a key symbol: betraying others, unable to voice their suffering, Deane’s male characters betray and debase themselves. Such self-hatred must originate somewhere – in some trauma. Pin’s mother, we learn, was a religious fanatic: ‘My earliest memories revolve around my mother’s fear of sin.’ Every night, ‘Mother Mary’ would sneak into his room and pray over his bed. Pin comes to believe that she prayed ‘not … to protect me from the devil [but] to protect her from me’. What chance does a boy raised to fear his own innate evil have of becoming a well-adjusted man?

The book is at its best in its lacerating depiction of masculine rites of passage and their consequences. At St Jude’s in the mid-1980s, an act of violence to rescue OB from a bully earns Pin respect, makes him ‘the talk of the school’, its ‘undisputed hard man’. OB, sensitive, artistic, receives merciless treatment due to rumours that he is the ‘bumboy’ of the Brothers, or Rasputins. OB’s chief tormentor is Cox. Yet while Pin does not like Cox, he recognises Cox’s power to shape the schoolyard narrative – a power that Cox will later wield in federal politics. After Pin spends the weekend at OB’s house, homophobic taunts fly. This fear of reputational damage overrides Pin’s fidelity to his friend. Deane’s raw, kinetic prose evokes the physical and emotional frenzy of what follows.

Less convincing are the scenes from Pin’s adulthood, and Deane’s portrayal of female characters. Aspects of the plot strain believability: that Jill would show Pin such charity after his abandoning her and Anna, letting him stay under the same roof as a child to whom he has not spoken in years; a bizarre beating Pin receives; Cox’s emergence as a figure in Jill’s life; a change in narration to a voice that resembles Richard Flanagan’s Death of a River Guide. Jill’s maternal ministrations, though she makes wisecracks about Pin’s misogyny, feel too forgiving, too self-effacing. We know little about her life. On the other hand, Pin’s Oedipal relationship with Aya O’Brien, OB’s mother, thirty-five when Pin is seventeen, presents the older woman as a bored and mistreated housewife whose seduction games begin when Pin walks in the door. Deane might have interrogated Aya’s blitheness towards unethical, if not criminal, behaviour. Still, Pin and Aya’s relationship is the strangest, most fascinating aspect of Judas Boys. It also features some of the strongest writing, demonstrating the gift for lyricism that has seen Deane publish three award-winning poetry collections. What Pin does with Aya’s wedding ring lingers in the memory. Another night, Pin and Aya are standing by OB’s pool. Aya, drunk, finishes her wine: ‘Then she threw her glass into the night sky. The wineglass caught the reflection of the kitchen light as it rose and fell in a perfect parabola.’

In Judas Boys, Pin has hurt so many people, and absorbed and enacted the traumatic narrative of himself as no good, as a Judas, so totally, that the road to redemption feels long. Yet condemnation of the man and sympathy for the boy can coexist. For Pin, telling OB’s story may represent the sort of testimony that could foster healing, or open a space for it. At OB’s funeral, Aya asks Pin what diving is like, but also ‘what it feels like to be good at something’. Pin answers: ‘It feels like falling out of or into a dream.’ In an early poem, ‘Freckle’, Deane depicts a boy standing on a tree branch above the Goulburn River:

He feels himself dissolve

as he dives deep into a dream,

arms pinned to sides,

where he finds himself double-kicking

beside a tram.

And in the window sits a man.

We wonder what kind of man the boy sees.

Comments powered by CComment