- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Caught in the fork

- Article Subtitle: The work, the life, his times

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Near the end of this biography of Frank Moorhouse, author Catharine Lumby tells a story that will strike retrospective fear into the heart of any male reader who has ever climbed a tree. Watching an outdoor ceremony in which a cohort of Cub Scouts was being initiated into the Boy Scout troop to which he belonged himself, and having climbed a tree to get a better view, the young Moorhouse ‘slipped, and he slid a couple of metres down the trunk of the tree with his legs wrapped around it. He came to rest on a jagged branch, his crotch caught in the fork.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kerryn Goldsworthy reviews 'Frank Moorhouse: A life' by Catharine Lumby

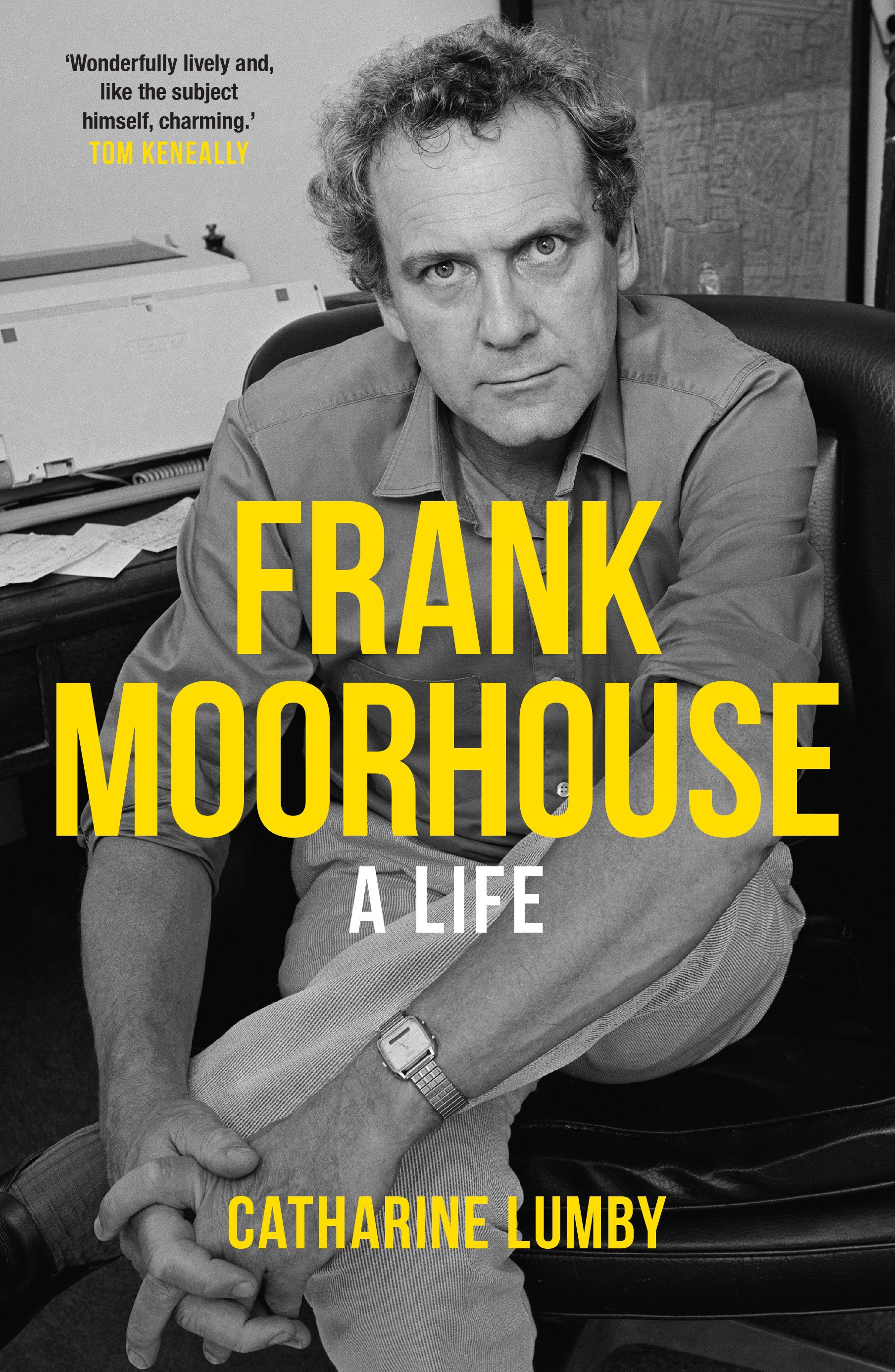

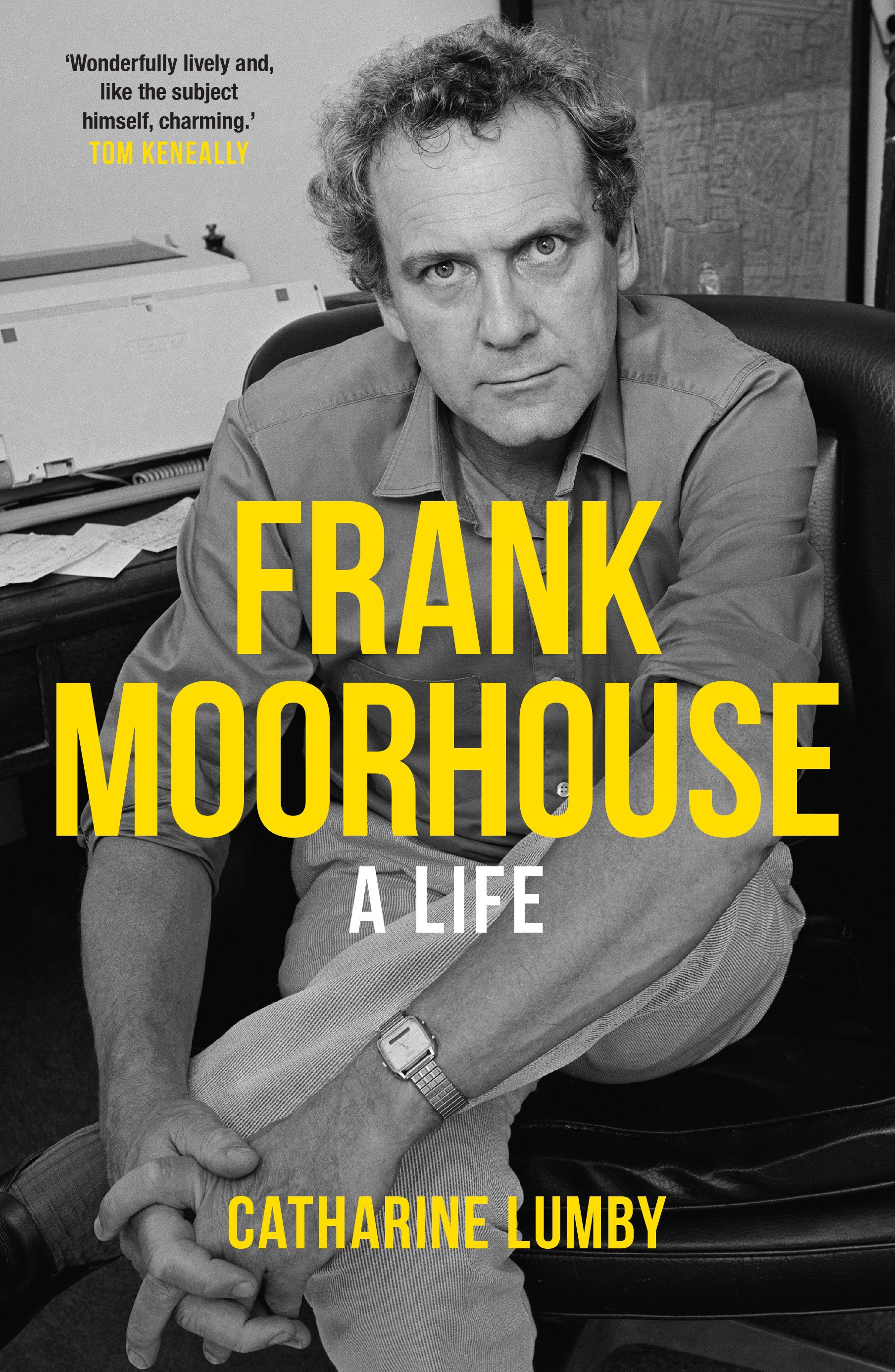

- Book 1 Title: Frank Moorhouse

- Book 1 Subtitle: A life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 303 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Back in the opening chapter, Lumby records that he was ‘profoundly influenced by reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland while bed-ridden for months at the age of twelve, [which furthered] his fascination with becoming a writer’. It seems unlikely that there would have been two different periods so close together of being confined to bed for over a month, and if this discovery of Wonderland happened when Moorhouse was bedridden while recovering from an injury he saw as nothing less than a symbolic castration, then three of the major themes of his life – his ambivalence in matters of sex and gender, his lifelong wrestle and fascination with the bush, and his vocation as writer – are all bound up with that one pubescent slip of the foot.

What we believe about ourselves is central to the formation and fashioning of the self, and telling the story of that self-fashioning is one of a biographer’s chief responsibilities and tasks. It’s to Lumby’s great credit that she gives priority, space, and respect to Moorhouse’s own beliefs about himself in this book about his life, so it is left to writer and scholar Fiona Giles, a close friend of Lumby’s, to perform a little gentle pushback about Freud. Giles was Moorhouse’s lover on and off for thirteen years, ‘one of the longest and most intimate relationships in the author’s life … she was, perhaps, his amour fou’. In an elegiac essay for The Monthly in the wake of his death, Giles wrote ‘Frank identified as Freudian, and often accused me of expressing displaced anger for my father instead of a problem, for example, with the washing up …’

But this book is an exploration of the three-way relationship between Moorhouse’s work, his life, and his times, rather than a detailed exploration of his romantic, sexual, and gendered lives – which, in any case, were so complex and varied that such a thing, if done thoroughly, would require not only several volumes but also a biographer without any of Lumby’s respect for other people’s privacy.

Her training and experience in journalism stand her in good stead as a biographer; the writing is fact-rich, lucid, and straightforward, without any sacrifice of complexity or nuance. She says in her Introduction that the book is thematic rather than chronological, but this is not entirely true; the first two chapters are the standard biographer’s account of boyhood, youth, and early manhood. After that, different themes and subjects take over as an ordering principle. She describes the book as ‘an attempt to connect the life and the work of an important Australian writer’, giving most of her attention in this respect to Moorhouse’s vast and ambitious ‘Edith trilogy’, three hefty novels about a young Australian woman called Edith Campbell Berry who goes to Geneva to work for the League of Nations and comes home, after its disintegration, to live and work in the newly established Australian capital.

Moorhouse’s massive archive is one of Lumby’s four main sources: the others are his prodigious output in the fields of fiction and nonfiction; the interviews that Lumby did with forty-five people who were significant in his professional or personal life; and her many conversations with Moorhouse himself. She makes no claim to be writing either an objective or a definitive account of his life: she describes this biography as both ‘selective’ and ‘subjective’. Moorhouse’s development as a writer and thinker, his place in Australian cultural life, and his efforts to improve the lives of authors and the quality of public discourse in Australia form the backbone of this book. Generations of Australian writers are and will continue to be indebted to him for his active and sometimes activist efforts, over decades, on matters of censorship and of copyright, and for his generosity in supporting and mentoring younger Australian writers.

‘Generosity’ is a word that comes up often; Moorhouse’s friend Rohan Hallam says ‘He’s one of the warmest, most generous, loving and affectionate human beings I’ve ever met.’ Fiona Giles remembers some beautiful gifts, as well as acts of kindness that indicated his vast generosity of spirit. But there are also some stories, notably the one from David Williamson, that reveal his capacity for snark. Moorhouse lived his life along a broader spectrum than most of us, and sometimes moved between its opposite ends at speed, blurring the middle point; Lumby observes, for example, that ‘It was never entirely clear when he was being serious and when he was being playful.’

His love of oysters and martinis, of fine dining and clubbable carousing, seems at odds with the physical discipline and fitness necessary for his regular bushwalking forays, usually undertaken alone. His legendary sociability was punctuated by an intermittent need for solitude. And perhaps the most obvious of these opposing forces in his life is the place where his elaborate sense of ‘rules for living’ – established in an orderly childhood that featured two strong, community-minded parents, as well as his love of Scouting and its ethos of preparedness – comes smack up against his love of freedom, both in personal relationships and in the relationship between the individual and the state.

A whole chapter of this book is entitled ‘Border Crossings’, and in it Lumby explores, with reference to Moorhouse’s work, some of these oppositions: such matters as the blurring of lines between erotica and pornography; the various boundaries being negotiated in cross-dressing and/or bisexuality; ideas about nationality, identity, and the crossing of national borders. Moorhouse’s work, as with his life, is one long set of negotiations between seeming opposites, and Lumby’s book about him is the portrait of an artist for whom the liminal zone was his natural home.

Comments powered by CComment