- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The ancestors

- Article Subtitle: An uncommonly good family history

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

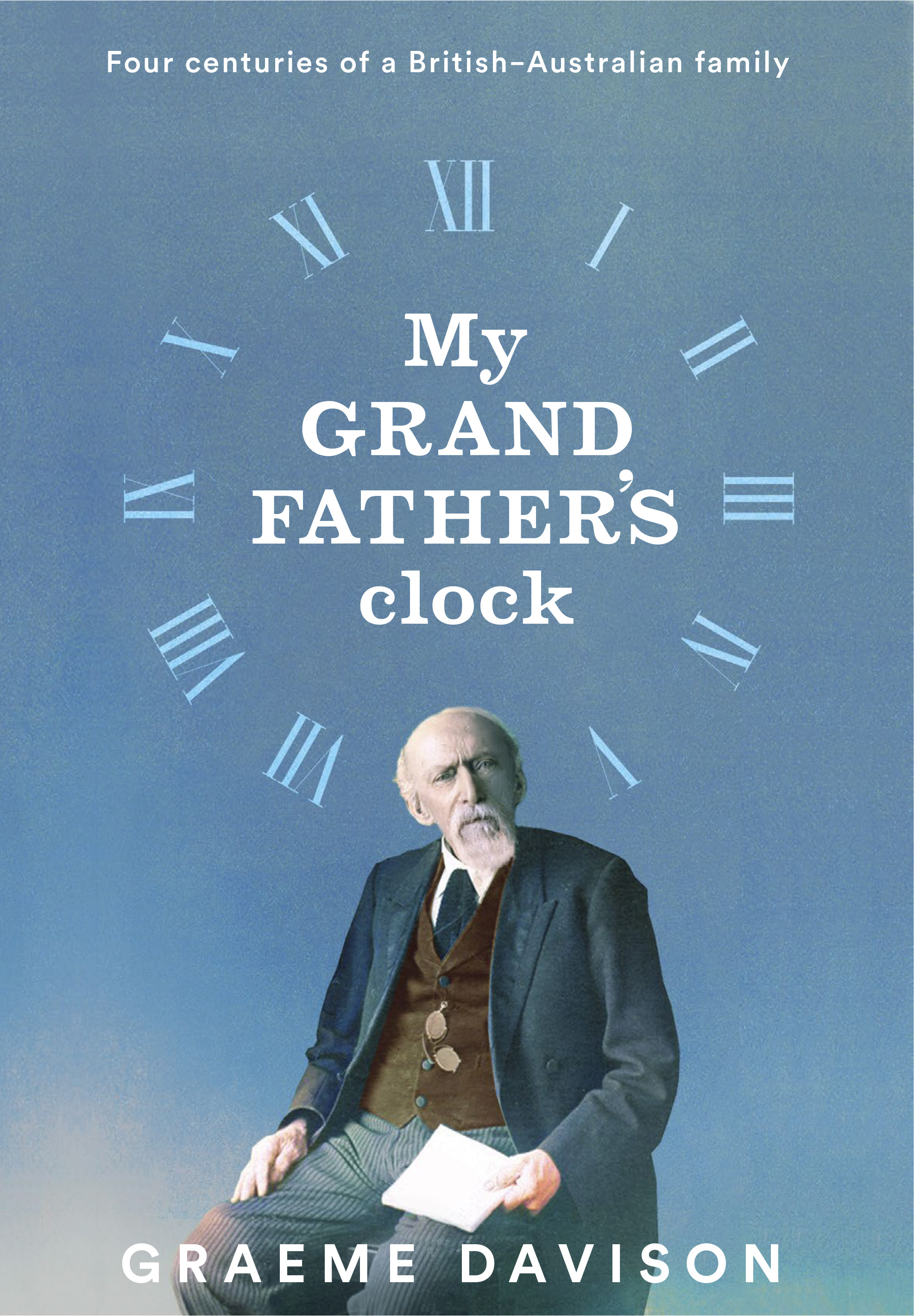

With My Grandfather’s Clock: Four centuries of a British-Australian family, historian Graeme Davison has offered his readers and bequeathed to his grandchildren a very special book, at once genealogy, travelogue, memoir, broad social history, and a meditation on the sources of personal identity. It is a book to be treasured.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Marilyn Lake reviews 'My Grandfather’s Clock: Four centuries of a British-Australian family' by Graeme Davison

- Book 1 Title: My Grandfather's Clock

- Book 1 Subtitle: Four centuries of a British-Australian family

- Book 1 Biblio: Miegunyah Press, $50 hb, 318 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The methods of genealogy and history are different in many ways. While the one proceeds backwards in time, the other moves forward. But in most kinds of history there are elements of both. In this beautifully written book, they work together to illuminate the great paradox of history as a mode of enquiry, that it is simultaneously of the past and the present, like the two-hundred-year-old grandfather clock of the title, which sets this engaging and peripatetic story in motion.

This is a transnational history. The Davisons had moved from the Scottish Borders to England. Davison’s father, George, migrates to Australia in 1912, aged just one year old. The clock doesn’t journey to Australia until later, when Aunt Cissie makes the journey in the midst of the Depression. Towards the end of the book, Davison returns to England as a Rhodes Scholar, and it becomes clear to him (although he would, on a later journey, be seized by ‘an attack of nostalgia for a homeland he had yet to see’) that he actually felt little connection to England. He was Australian and his future lay in the country in which he was born, writing the history of his city.

As a historian, Davison has long been interested in clocks and watches and the history and significance of telling time. He cites English historian David Landes’ observation that a common measured time was the foundation of the modern world. Davison’s book The Unforgiving Minute (1993) documented the history of time-telling in Australia. He has also been interested in museums and material culture. The tall clock now in Davison’s Melbourne home features in this history as many things: mechanical wonder, family heirloom, object of desire, talisman, repository of wisdom, and alibi for a search for personal identity. It ‘demanded to be read’, he notes, ‘both as history and heritage, for its meanings in history and for me’. There was a family legend, told by Uncle Frank, that when he visited grandfather Thomas in Birmingham in 1929, the clock had struck. ‘Listen,’ the old man had exclaimed, ‘our ancestors.’

When the Davison family moved from Annan to the garrison city of Carlisle early in the nineteenth century, they completed a journey that began in East Teviotdale a century before. They were becoming attuned to the values that were beginning to shape everyday life in an industrial city. ‘We know this,’ writes Davison, the historian of timekeeping, not because of anything they said or wrote, ‘but because of something that [the] family owned.’ It was at this time that they probably acquired the grandfather clock from their neighbour, the clockmaker Robert Hodgson. ‘It was a significant purchase for it showed that my ancestors not only wanted to tell the time, they also wanted to be up with the times.’ The Davisons were agents of modernity. In the future, when the clock is inherited by Davison’s son, this heirloom will have passed through seven generations.

When the Davisons moved from rural life to an industrial metropolis, they left behind the old agricultural cycles of sowing, growing, reaping, and droving, and found themselves in a place where factory bells and whistles announced the beginning of the working day, although as ‘handworkers’, whose workplaces often adjoined their living quarters, the Davisons more likely listened for the metallic ding of Robert Hodgson’s long-case clock.

One of the many achievements of this uncommonly good family history is the broader social history it offers – describing the effects of the industrial revolution, technological change at the workplace, the sudden redundancy of many skilled workers (such as weavers and block-printers), and urban growth. In the hands of a skilled historian, family history can open windows onto wider worlds. In My Grandfather’s Clock, the historian of Marvellous Melbourne pores over maps and other sources to explore the expansion of Carlisle and Birmingham and their industrial suburbs. He joins an old debate about whether industrialisation benefited workers and suggests that William Davidson, born in 1782, growing potatoes and earning twenty-five shillings a week as a block-printer at Cummersdale, was probably better off than his son and grandchildren, living in poverty, overcrowding, and disease at Caldewgate, an industrial suburb of Carlisle.

Thomas Davison, William’s grandson, was fortunate as a choir boy to be educated at the Cathedral Grammar School. He later moved and found work and new status as a tin-plater in Birmingham, the ‘workshop of the world’, which made everything from billycans to bicycles, from guns to electrical generators. He was elected president of the Birmingham Operative Tin-Plate Workers’ Society and supported the movement for parliamentary reform. He became manager of the firm, JH Hopkins and Sons, but then his fortunes plunged.

In noting the precariousness of life for so many, Davison suggests that both education and emigration might offer escapes from poverty. In 1912, Thomas’s son John decided to take an assisted passage with his wife, Ada, and young family, voyaging third class on the SS Orestes to Melbourne. The family had also moved from Church to Chapel, forsaking the Church of England for Methodism. ‘In becoming a Methodist,’ Davison writes, ‘John was embracing a distinctive culture, with its own sense of time and history. Some of that culture would be transmitted to me, along with the ancestral clock.’

As Zerubavel has also observed, genealogical narratives don’t simply trace a family tree; they also serve to transform these grandfathers and great grandfathers into one’s ancestors. Davison, looking back at them, finds continuities and affinities. Biology is not destiny, but cultural values, he suggests, are passed on. They can also be rejected. ‘I didn’t remain a teetotaller for long,’ he writes, ‘but I’m glad Richard [Thomas’s father] took his stand: we might all be back in Caldewgate if he hadn’t.’ Listen to the ancestors.

Comments powered by CComment