- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Diversity and invention

- Article Subtitle: Two new poetry collections

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

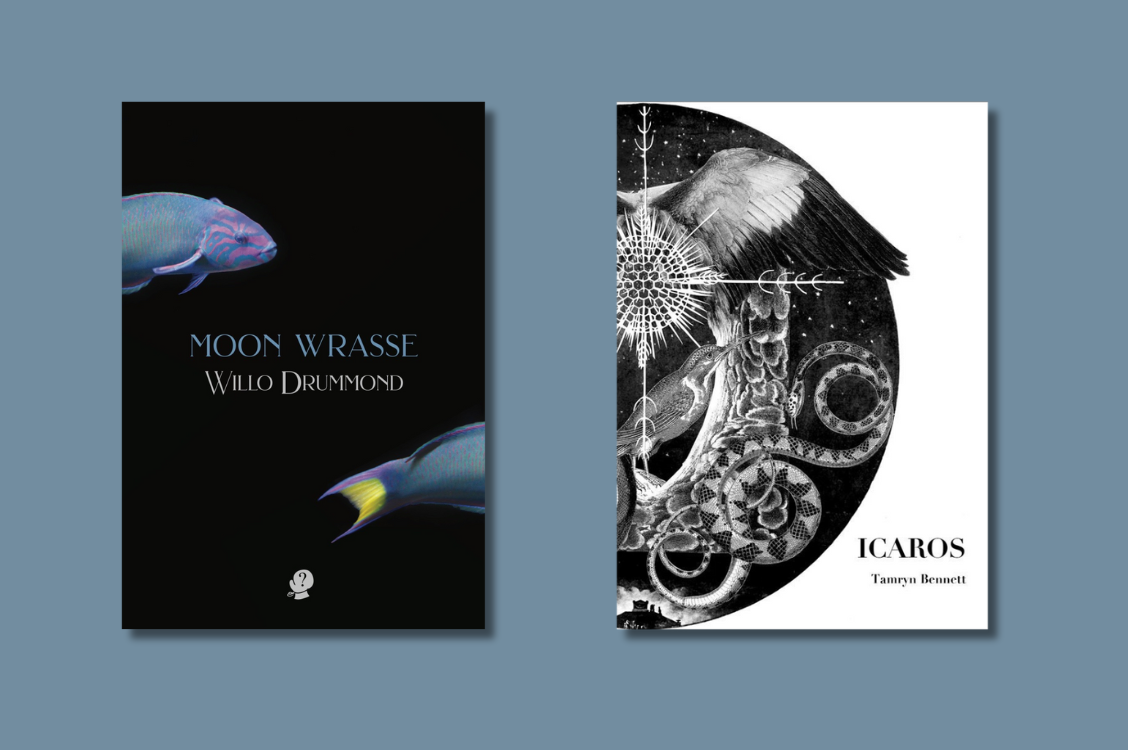

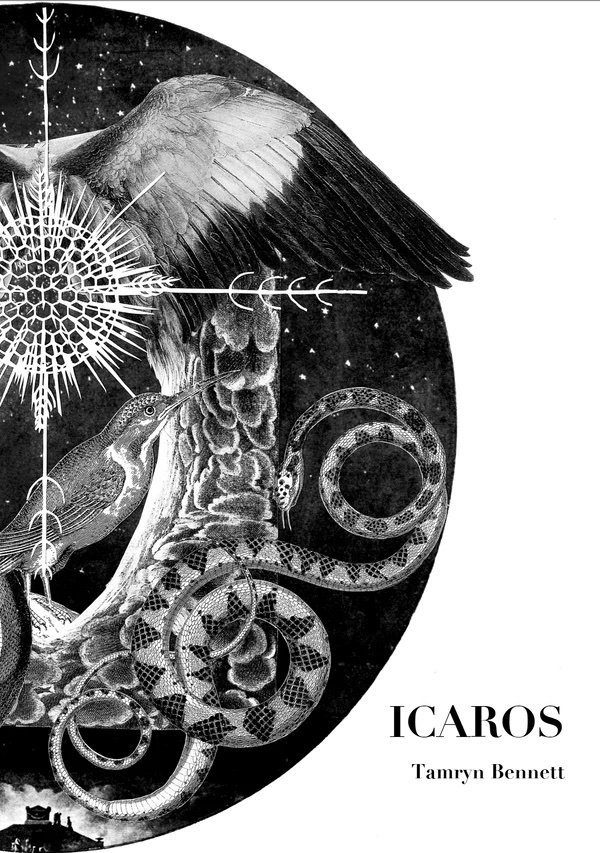

Tamryn Bennett’s Icaros and Willo Drummond’s Moon Wrasse both use the natural as their central motif. Nature has of course always been a font of inspiration for poets. These two poets draw from that font in vastly different ways. Bennett’s title refers to a form of South American song that is chanted during rituals of cleansing and healing that involve plants. Drummond’s refers to a hermaphroditic fish, the moon wrasse, which acts as a symbol of transformation.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sam Ryan reviews two new poetry collections

- Book 1 Title: Icaros

- Book 1 Biblio: Vagabond Press, $25 pb, 96 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Moon Wrasse

- Book 2 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 84 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Imagery is extremely important in Icaros. Cavallaro’s art weaved through the poetry guides and engages the reader, granting a visual atmosphere to the work. ‘All those made ash’ describes a ritual involving ‘herbs of hag and hell broth’ that uses ‘Onion, garlic, acacia and peach, / heliotrope, wormwood’ which is ‘wound around the antidote’. It seems to engage in that familiar folk tale of witches hunched over a cauldron, listing the ingredients that make up their malicious potion. It resists that tale, emphasising the healing properties of such communes with nature. The poem takes up four pages, consisting of two double-page spreads. The first, where most of the poem’s words appear, is framed with drawings of what looks like coral or a dense thicket. The second includes, on its first page, the couplet ‘All those made ash / for knowing too much’, and on its second, the silhouettes of three figures standing with arms outstretched holding what appears to be skulls. Empty silhouettes of fish swim across the figures. The white space of the figures’ silhouettes is filled in with the same coral from the previous double-page spread. That coral, or thicket, represents the natural; just as the witches who contain the natural were punished for their forbidden knowledge, so too it seems is the natural that fills them.

In addition to Cavallaro’s visual images, Bennett’s poetry drips with rich literary imagery. In ‘twinning snakeroot into sleep’, there are ‘bones flowering’ and ‘museums of lichen’, describing ancient knowledge of a poisonous plant. In ‘long burned’, trees are described as ‘the dead ribs of forest / that once held crane and mastodon’. Nature in these poems is an ally both dangerous and nurturing. Bennett anthropomorphises it as a warning that we destroy it at our peril.

Moon Wrasse opens with the poem ‘Seed’, which introduces the reader to Drummond’s thesis: that poetic dialogue is transformative and that transformation can be transgressive, difficult, and inevitable. The seed in this poem is filled with grief and then set out across a river. The poet ‘trains her eye / to the velvet vivipary / on very salty water’. The seed is one which may germinate too soon. This may be a reference to the poet’s own experience with fertility, as alluded to in the book’s blurb, or perhaps in a third-person sense to a journey in gender identity and transformation while still subject to pressure from parents. That salty water on which the seed must survive surely refers to the inhospitality of wider society to such transformation. Its very existence is a transgression. Drummond’s dialogue with other poets begins here with ‘what cannot be / is’, set in italics in the poem’s final two triplets. These words come from Jennifer Moxley’s essay ‘Lyric Poetry and the Inassimilable Life’ (2005), where she claims that lyric poetry can record voices which are structurally barred from political and social power.

Drummond dialogues not only with poets. In ‘Propagules for drift and dispersal’, she employs lines such as ‘the mangrove is probably the most remarkable / community of unrelated families in the world’, which is borrowed from scientific writing about mangroves. The sense of literary transformation here is palpable; Drummond takes the non-literary and makes it literary. I doubt I would have made this connection without the assistance of the book’s extensive notes.

While the notes in Moon Wrasse certainly bring its literary quality to the fore, and surely make its scholarly dissection less painful, I wonder if they are necessary. I’ve had conversations with James Joyce scholars about his provision of the Ulysses schema to Valery Larbaud, where my view could be summed up in that maxim: ‘If you have to explain a joke, it isn’t funny.’ I was being facetious there as I am here: the more I read the notes alongside the poetry, in both Drummond and Joyce, the more I understand that some complex humour requires explanation. However, Moon Wrasse’s notes may speak down to an academic reader and intimidate the general reader. That doesn’t detract from the quality of the poetry, but I think their inclusion was a mistake on behalf of the publisher. The poems are powerful and engaging without the bibliography.

In contrast, Bennett resists the literary so much that the poetry in Icaros is barely titled. Rather, each poem contains a bolded line that acts as a title and is noted as such on the contents page. This seems to distance the poetry from being read as purely literary, eschewing the categorisation that titling brings in favour of the words and images themselves. This kind of resistance to the literary works well almost everywhere in the book, except in a few places where the alignment and indentation of stanzas forgoes what we would expect in poetry, and instead empathises the visual elements, occasionally at the cost of the literary.

Regardless of their minor shortcomings, which are both likely matters of personal taste, these are brilliant books of poetry that reflect the vivid diversity and invention which is becoming characteristic of Australian poetry. Any reader of poetry will find satisfaction in these pages.

Comments powered by CComment