- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fischer's life

- Article Subtitle: From Boree Creek to Bhutan

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

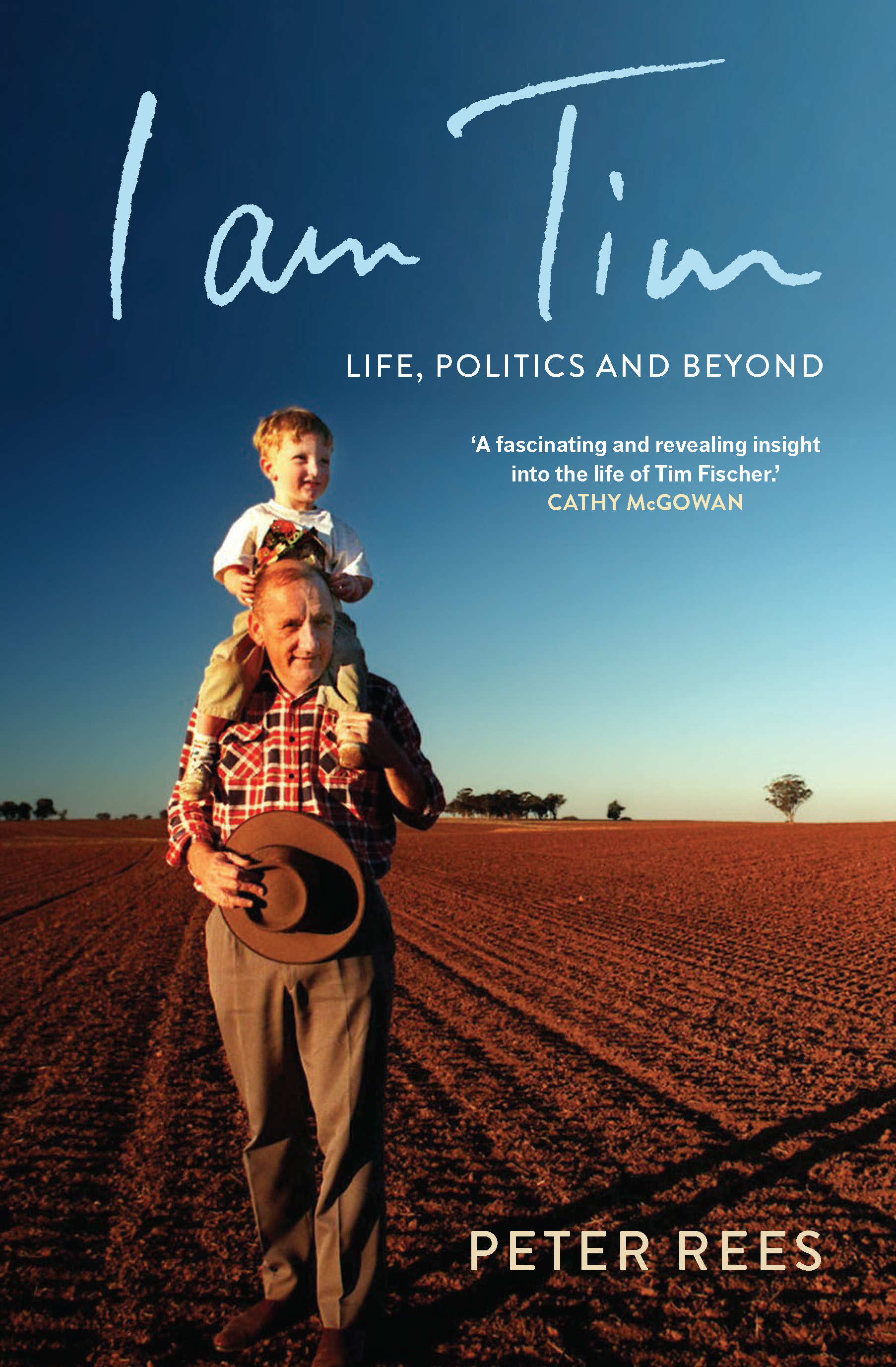

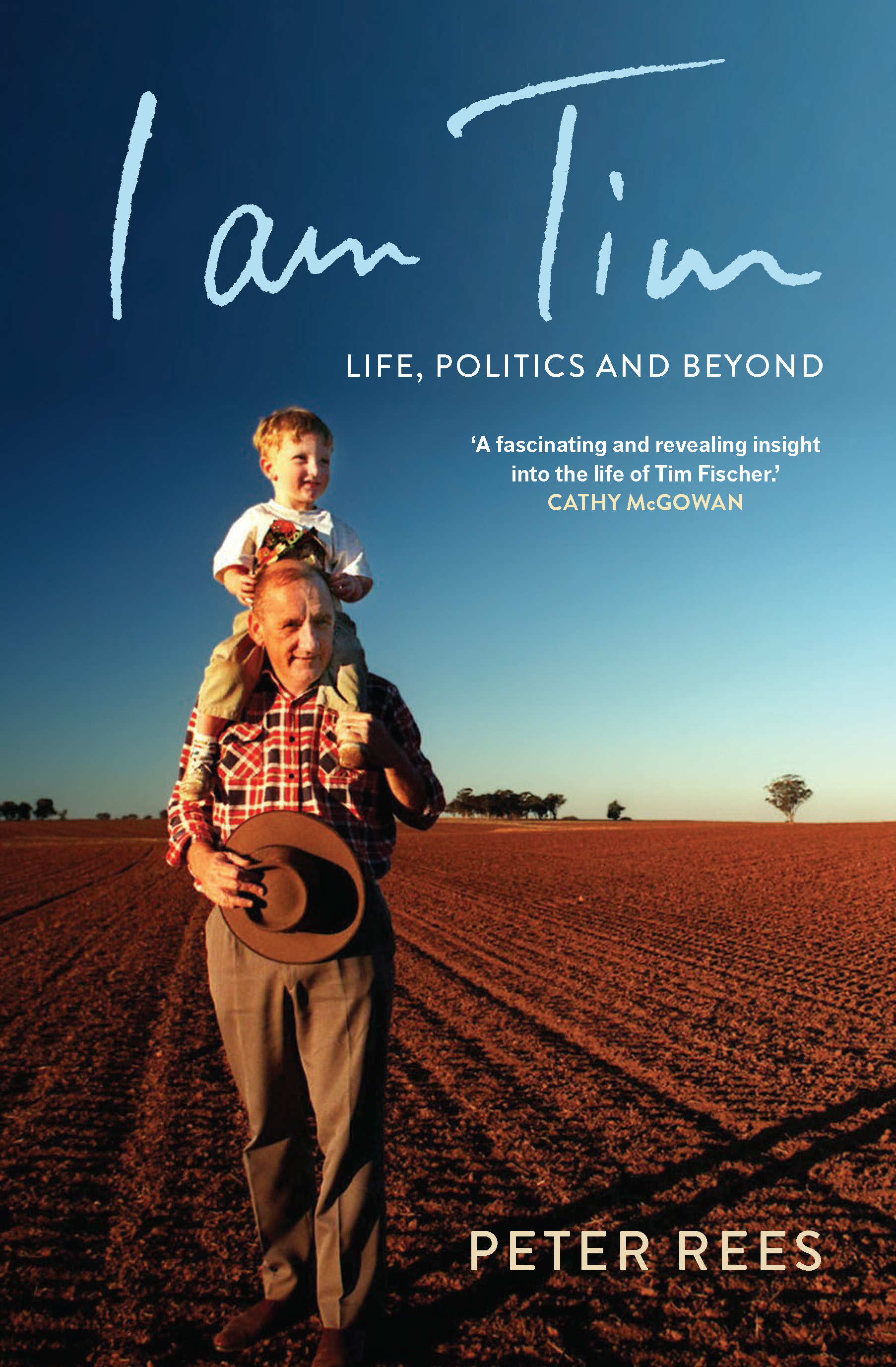

Journalist Peter Rees’s biography of Tim Fischer was originally published by Allen & Unwin in 2001 with the title The Boy from Boree Creek. Reviewing the volume in this magazine, fellow journalist Shaun Carney had many kind words for Fischer, but said that the book was ‘either a lesson in the wonders of our democracy or a cautionary tale demonstrating the mediocrity of our public figures’ (ABR, June 2001). The subject was a ‘decent, determined, and hardworking person’, Carney wrote, but one who left the National Party in ‘a seemingly permanent existential crisis’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Joshua Black reviews 'I Am Tim: Life, politics and beyond' by Peter Rees

- Book 1 Title: I Am Tim

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life, politics and beyond

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $40 pb, 415 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

To young Australians, Fischer might only be recognisable as the target of Paul Keating’s ridicule in YouTube compilations of the former prime minister’s one-liners. I Am Tim offers a more nuanced view. Born to a pastoral family in Boree Creek in 1946, Fischer’s formative years were shaped by the ‘homesickness’ that went with Jesuit boarding school, the cultural politics of the Cold War, and especially his compulsory national service during the Vietnam War and the harm to which it exposed him. In 1971, aged just twenty-four, he won preselection for the Country Party and became the ‘first Vietnam veteran to be elected to any Australian parliament’, representing regional Sturt in the New South Wales parliament. Having made the switch to federal politics in 1984, he emerged as an eccentric, an economic rationalist, a ‘media junkie’, and eventually leader of the rebadged National Party (1990–99). Upon his resignation as leader, Fischer was lionised as ‘one of the very genuinely loved people in this place’ (as then Opposition leader Kim Beazley put it).

Fischer’s was also an impressive life of post-ministerial service, probably too much so for his family. The family’s challenges in managing son Harrison’s Autism Spectrum Disorder are on the public record. Duty was clearly a powerful motivation for Fischer, but given the time he spent travelling to his favourite destination, Bhutan, supervising elections in East Timor (about which there was more to say), and serving as full-time ambassador to the Holy See in Rome, it is hard to escape the conclusion that the hardest sacrifices were borne by his wife Judy and their sons. (Judy is recognised as an important advocate in her own right in this book.)

Fischer’s life makes for an especially interesting vehicle for telling the history of the National Party. Fischer’s active years in the movement saw the decline of its old ‘Protection All Round’ approach to political economy and the rise of neoliberal, free-market thinking in its place. The ascent of Pauline Hanson posed a particular challenge for the party, and much of Rees’s account concerns Fischer’s attempts to assert the relevance of the old party in the face of the new challenger. As deputy prime minister, Fischer was closely involved in the Howard government’s national firearms agreement, a reform that brought ‘intense pressure’ to bear on the party in rural Australia. The ‘existential crisis’ that Carney described was eventually resolved by leaders who turned the party into the parliamentary wing of the ‘fossil fuel lobby’. But it has to be said that, long before Barnaby Joyce, the party was already so bereft of ideas that it equated the Akubra atop the leader’s head with ‘a carefully planned strategy’ for communicating with rural Australia.

Rees and Fischer knew each other well from their overlapping years in Canberra. They had written and published together. They were friends. Rees’s affinity with Fischer is borne out in the exaggerations or compliments paid to him in this book. Fischer and Howard were hardly ‘one of the great double acts of leadership’, as is claimed. Fischer is on record saying that it was his games of snooker with Mexico’s trade minister that led to ‘a renewal of trade links’ between the two nations, a somewhat fanciful claim Rees does little to qualify. But in fairness, he is clear-eyed about the less savoury aspects of Fischer’s legacy. For example, there was the shameless pork barrelling of the conservative parties in their campaign for re-election in 1998 (Fischer himself called it this in diaries). There was also his uncompromising stance on sexuality, gay rights, and the censorship of sex-education materials in schools.

Steeped in the pioneer legend of rural Australian politics, Fischer and his party were especially antagonistic towards native title reforms in the 1990s. There is no gainsaying it: Fischer’s oratory was racist. He was dismissive of pre-contact Aboriginal societies, contemptuous of the High Court of Australia, and committed to ‘bucketloads of extinguishment’ of native title. Reckoning with this, Rees recognises the distinct nature of Aboriginal custodianship of Country, and the structural erasure of Aboriginal culture from the history books on which Fischer’s generation was raised. Rees draws wisdom from Henry Reynolds, leading historian and advocate for the recognition of native title, who is quoted as having ‘some sympathy for Fischer’: ‘It’s hard to imagine how the leader of the National Party could have reacted in any other way.’

Like Reynolds for Fischer, I have sympathy for Rees’s attempt to do justice in this account, but the circle between Fischer’s self-professed abhorrence of racism and his pronouncements against native title cannot be squared. There were others in the rural sector, like National Farmers’ Federation executive Rick Farley, who modelled the kind of political imagination that was available to Fischer. Rees says that Fischer’s life was ‘circumscribed by institutions with rigidly defined world views’, but, by that same logic, Fischer may well have been a protectionist.

I Am Tim is a sound political biography. In places, it is too deliberately lyrical, too repetitive, and too dependent on the clichés that abound in modern political language. But these qualities are outweighed by the earnestness, respect, and warmth of the author’s voice. Rees’s friendship with and admiration for Fischer have not hindered a complicated and multifaceted portrait. But the updated volume still fits Shaun Carney’s assessment of the original: it is either a moving eulogy for a decent man in a not-so-decent profession, or a respectable account of an admittedly uninspiring figure. Rees does not drive the reader into one camp or the other.

Comments powered by CComment