- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Children's and Young Adult Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Three new Young Adult novels

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Gender and power

- Article Subtitle: Three new Young Adult novels

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Three new novels from Allen & Unwin explore gender power relations – with mixed results. In Ellie Marney’s Some Shall Break ($24.99 pb, 382 pp), a young woman helps law enforcement hunt a serial killer who is kidnapping and raping young women. Garth Nix’s latest offers interesting parallels, though The Sinister Booksellers of Bath ($24.99 pb 330 pp) includes plenty of fantasy elements to vary the formula. Meanwhile, Kate J. Armstrong’s Nightbirds ($24.99 pb, 462 pp) follows three different women who are navigating magical, political, and romantic intrigues.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ben Chandler reviews three new young adult novels

- Book 1 Title: Some Shall Break

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.99 pb, 382 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: The Sinister Booksellers of Bath

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.99 pb, 330 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

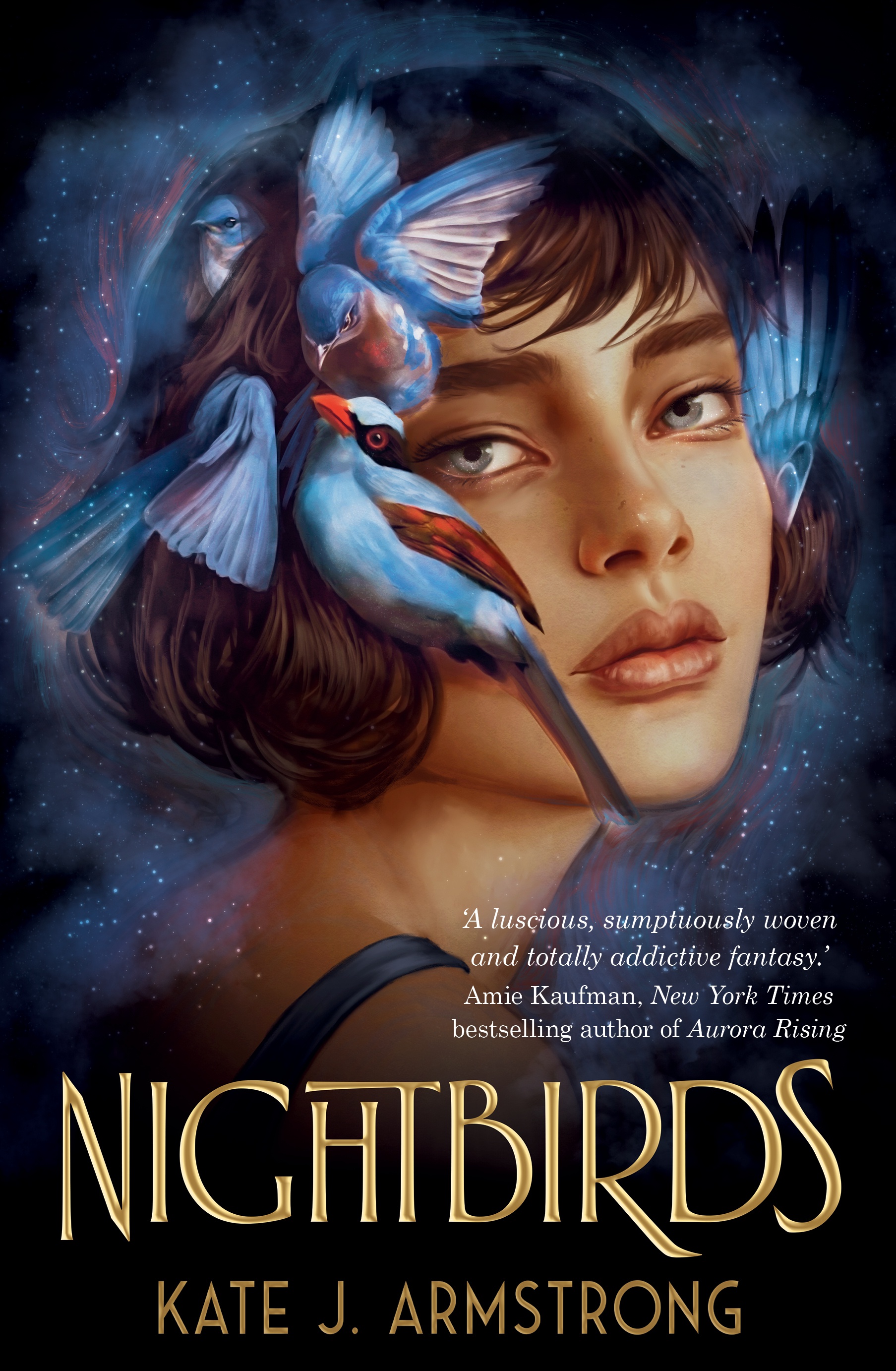

- Book 3 Title: Nightbirds

- Book 3 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.99 pb, 462 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The rest of Marney’s characters are equally flat. Emma is a traumatised survivor, and that’s about it: tough exterior, short-cropped hair, brooding silences, no nuance. The romance between her and Travis, a similarly uninspired cliché of a strait-laced field agent, is sparkless, though sweet in places. They both think, talk, and act as though they are considerably older than they are, which doesn’t help. The only character with any real dimension is Kristin, Simon’s twin, who injects some much-needed personality as she struggles to reconcile her attachment to her brother with the things he has done, which includes murdering a young man she was sweet on. She pops whenever she appears on the page. Marney’s prose is as clinical and concise as a police report, which distances the reader at first but clicks into gear about halfway through, when a new girl is kidnapped and some much-needed urgency is injected into the hunt. In the final eighty pages, the tension fires up and Marney’s clipped prose becomes a boon. The action pivots masterfully between two equally engrossing settings, impossible to discuss without giving the game away, that leave the reader wondering why they had to wait so long for anything to happen. Provided readers can get through the tedious initial investigation and are willing to ignore a few too many contrivances, and one final act of authorial intervention necessary to line up all the pieces, the climax delivers on the promised thrills.

The Sinister Booksellers of Bath – another sequel set in the early 1980s – features a young woman with a buzzcut called in by law enforcement to help hunt a serial killer because of her past, but Nix’s offering does much more with the formula. The law enforcement in Nix’s slightly fantastical version of Bath are the booksellers, England’s official, if secretive, government agency charged with protecting the world from magical entities. They also sell books. Booksellers come in right-handed, even-handed, and the titular sinister (i.e. left-handed) varieties, which determines the abilities they possess. Young adult protagonist Susan is no bookseller, but she has inherited magic that provides an angle into the investigation that the booksellers lack, making her feel much more essential to the plot than Emma. The serial killers on offer here, including the one Susan goes to for crucial advice midway through her investigation, are eternal entities known as Ancient Sovereigns. Their inhumanity and immortality make it easy to buy their lack of empathy for their mortal victims, but this does mean Nix can’t use them to offer fresh insights into the human psyche, as Marney tries to. At least each Ancient Sovereign is visually distinct and interesting, including one formed from a collection of ravens. There is enough action to keep the plot moving along, though Nix’s attention to detail, particularly when it comes to clothing, accoutrements, book editions, firearms, and the like, may try the patience of some readers.

Those who buy into the premise of a gaggle of pedantic booklovers solving crimes through research should luxuriate in how Nix turns an admittedly elongated phrase. This is a book as much about celebrating books as it is about murderous fantastical beings. Thankfully, Nix does not rely on magical McGuffins to resolve his plot points. The booksellers’ magical abilities seem incidental to their true superpower: reading.

Armstrong’s Nightbirds also explores how relationships between men and women are mediated by power, literal, political, and magical. Certain women inherit magic powers that the church has deemed heretical. Such women are hunted down, their fate ambiguous but terrible. What elevates Armstrong’s work beyond this tired fantasy trope is the political landscape she layers on this foundation. Wealthy and powerful families protect the titular Nightbirds and their magic, taking it from them as payment via consensual kisses and using it to bolster their own fortunes. These women charge for their services, in cash and secrets, gaining further protection but raising questions about how close to prostitution this arrangement is. Characters discuss this connection, but Armstrong shies away from examining it, focusing instead on how these girls navigate high society and their quest for suitable husbands before their magic fades, as it will over time. It is Austen on steroids as the three focal characters – Mathilde, Sayer, and Æsa – weave between political factions, social strata, romantic entanglements, assassination plots, magical battles, and revelations that threaten to upend this precarious system in different and interesting ways. The sense of danger is omnipresent and multifaceted. Armstrong does belabour her central metaphor of birds in gilded cages and tends to unnecessarily restate her characters’ motivations, especially for Æsa, who grew up outside the Nightbirds system and struggles with her magical heritage as a devotee of the church who has internalised their messages about dangerous women, but this rarely stalls the pacing. The romances are scintillating, genuine, and deep, including an obvious but well-crafted triangle, the resolution of which has high political, social, and personal stakes. It is engaging and fun, though the climax is spoilt by Armstrong’s unfortunate deployment of a ‘To Be Continued’ to forestall the resolution of too many of her plotlines, leaving this instalment feeling unfinished, with a sequel eagerly anticipated.

Each of these novels explores how power dynamics intersect with gender. It’s a testament to all three authors that none of them does so with a heavy hand, focusing instead, with varying success, on crafting engaging protagonists and plots. Marney’s Emma fights endlessly against men who want to possess, control, use, or destroy women. Nix’s Susan craves the power she has inherited, resents the price she pays for it, is determined to use it for a greater good, and strives to remain unchanged by it. The three women in Armstrong’s novel are born with social and magical power but are powerless in the face of the political and social structures that oppress them, until they aren’t. Each character already possesses power, but it’s not until they find their agency that they can overcome the barriers they face.

Comments powered by CComment