- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A time of transness

- Article Subtitle: A new phase in trans literature

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A lot can change in a few years. In March 2020, on the eve of the Covid-19 pandemic, I wrote a review essay for ABR about the proliferation of trans and gender diverse (TGD) life writing. Back then, the most notable examples came from overseas, and – with the exception of established names like ABC’s Eddie Ayres (now Ed Le Broq), author of the 2017 memoir Danger Music – major Australian publishers had yet to take a chance on local trans voices.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Yves Rees reviews 'A Real Piece of Work: A memoir in essays' by Erin Riley

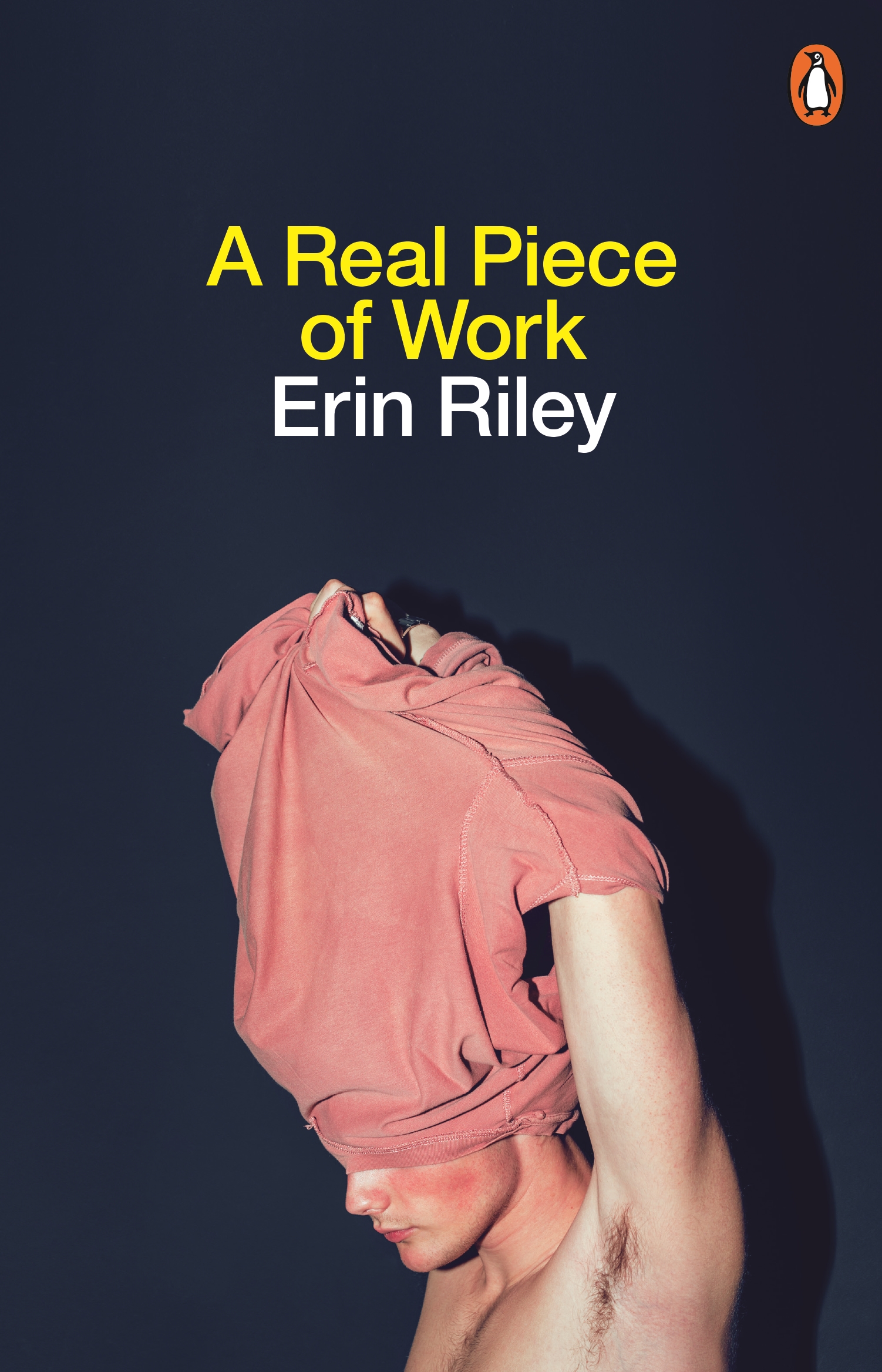

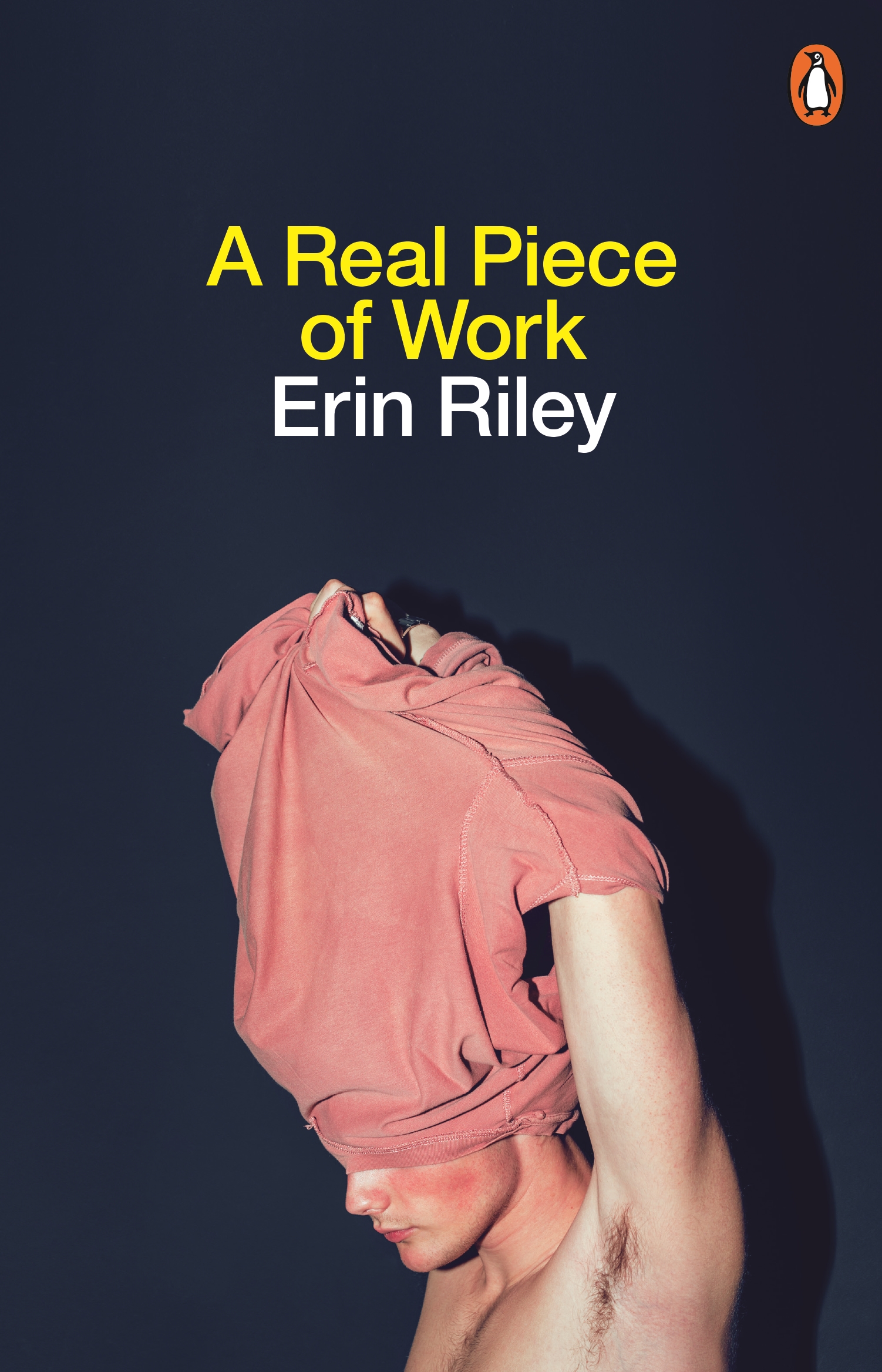

- Book 1 Title: A Real Piece of Work

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $24.99 pb, 252 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The latest addition to this fast-growing canon of Australian trans literature is Erin Riley’s A Real Piece of Work, a ‘memoir in essays’ that emerged from a 2021 Penguin Random House Australia Write It Fellowship, a fellowship scheme designed to nurture unpublished writers from under-represented communities. A Sydney-based social worker, Riley is a non-binary transmasculine millennial who has previously published standalone essays in Kill Your Darlings and Bent Street. Their début book, A Real Piece of Work, is a slim volume composed of twenty-one essays – some brief sketches only a few pages long; others deep dives into thorny topics that merge storytelling with structural analysis. The topics are wide-ranging: ocean swimming, wrestling, marriage, home ownership, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social work, routine and exercise all come under the microscope. What unites these varied foci is a concern with questions of family and care. How do we navigate our natal families and build our chosen ones, and what form can these families take? How do we look after ourselves and others in a world that undervalues – even disdains – the labour of care?

Although the question of Riley’s transness is a recurring theme, and gender affirmation surgery forms the book’s climactic moment, gender transition is not the central story here. Rather, A Real Piece of Work is better described as a work of cultural criticism written via a trans and queer lens; transness as a way of seeing, as opposed to the preoccupying subject. This project is made explicit in the essay ‘Maggie and Olivia or’, in which Riley draws upon queer theorist Eve Sedgwick’s concept of reparative and paranoid readings to explore how transness might allow us to view the world anew. For Riley, ‘reparative reading is a trans reading, one less concerned with binaries and definitions than it is with playing a role in the expansion of queer understandings and possibilities’.

As a work of trans criticism, A Real Piece of Work is best understood within the tradition of queer essayists such as Maggie Nelson, Olivia Laing, Alexander Chee, and Fiona Wright, all of whom use their life as raw material to interrogate contemporary culture. Despite what the marketing materials may suggest, a straight memoir this is not. This departure from conventional life writing is in part an act of self-effacement – in the Afterword, Riley acknowledges their reluctance to write about themselves – but it can also be seen as evidence of a welcome new phase in local trans literature. No longer is transness such a novelty that it must form the central subject of any writer who inhabits that identity. We can now accommodate authors who happen to be trans, who use that transness to interpret the world, but who are also three-dimensional humans with capacity to think and write on many things.

The most compelling essays are those in which Riley grapples with social work, a caring profession embedded in histories of colonial and class violence that nonetheless aspires towards justice in the present. By presenting composite case histories from their work, Riley forces us to look at the human fallout of systemic inequities, while asking to what extent social workers can pick up the pieces. Also notable are Riley’s pieces on everyday routine and ritual, gentle ruminations in which the quotidian rituals of drinking coffee or walking the dog are afforded a nobility often missing in the rush towards the more Instagrammable moments of travel and achievement.

Whereas essayists often come to the page armoured by theoretical references and ironic distance, Riley writes with an unwavering earnestness so heartfelt that it promises to wear down even the most cynical reader. Everything has been left on the page, including the author’s still-beating heart. At moments, especially when the author’s familial estrangements are under discussion, it hurts to look. This here is the wound, most definitely not the scar. While it can feel almost voyeuristic to witness such vulnerability, Riley’s distinctive voice offers a refreshing alternative to the unspoken rule that critical intelligence must take the form of prose drained of emotion and sharpened to a fine point. In these pages, Riley is modelling a new way to be smart: soft and tender and sweet.

Comments powered by CComment