- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Double daylight

- Article Subtitle: The horrors of British atomic testing

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In April 1952, during the long voyage from Portsmouth around the Cape to the Montebello Islands off the coast of Western Australia, HMS Narvik and HMS Zeebrugge anchored at the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean. After a slow, lurching trip, the palmy islands and their azure seas were a tonic. There, the crew of the British ships met for the first time with the legendary RAAF No. 2 Airfield Construction Squadron that had built the Woomera rocket range in South Australia and was then building a civil airport on the islands. Five British crew decided, against an explicit order from the Australian Commander, to take a swim. In the treacherous reef waters, they quickly got into trouble and RAAF servicemen went to rescue them. The Prologue to Operation Hurricane gives a harrowing account of how three men drowned: one of the Brits and two of the Australian rescuers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Elizabeth Tynan reviews 'Operation Hurricane: The story of Britain’s first atomic test in Australia and the legacy that remains' by Paul Grace

- Book 1 Title: Operation Hurricane

- Book 1 Subtitle: The story of Britain’s first atomic test in Australia and the legacy that remains

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $34.99 pb, 367 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

On 3 October 1952, esteemed British mathematical physicist and Manhattan Project veteran Dr William Penney gave the go-ahead for the detonation of the Hurricane bomb at that remote Australian atoll. He was aboard another ship in the flotilla, HMS Campania. This maritime test for a maritime nation played out a scenario that was exercising British minds: what would happen if an atomic bomb was detonated in a port? The device, designed by Penney, was stowed in the hull of a surplus Royal Navy vessel, HMS Plym, anchored just off Trimouille Island, part of the Montebello group.

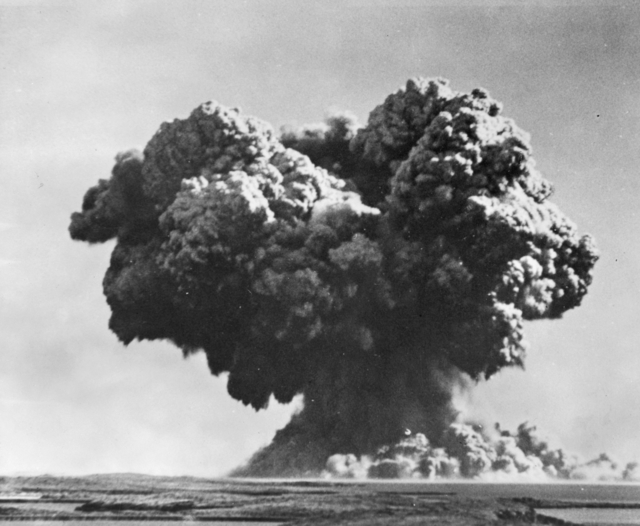

Britain’s first atomic weapon detonation, 1952 (Australian War Memorial via Wikimedia Commons)

Britain’s first atomic weapon detonation, 1952 (Australian War Memorial via Wikimedia Commons)

Montebello had been chosen after an extensive search. Britain took care to exclude its own territory from consideration on the grounds of physical and political risk. Many former colonies were assessed, Canada prominent among them, but in the end the British settled upon some flat, uninhabited islands 120 kilometres off the coast of Western Australia.

What occurred there was a momentous, but largely unknown, event in Australian history. Paul Grace has captured the story of Operation Hurricane in honour of his grandfather Ron Grace, who was a RAAF Dakota pilot flying coastal monitoring sorties. In doing so, he has told a compelling tale of British ambition and the people who suffered for it.

Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies quickly gave his assent to the top secret British plans. Grace raises the interesting (though unanswerable) point that a Labor government would probably have agreed to atomic testing too.

Grace’s strength is his ability to build dramatic tension and confront readers with the emotional heft of extraordinary events. He recreates the atmosphere of that momentous first British fission weapon blast by taking the reader through the countdown, performed with clinical precision by Ieuan Maddock, assistant director of the telemetry and communications division of High Explosives Research, a British organisation that was later known as the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment, maker of the British bombs.

Curiously, for a book rich in anecdote and fascinating detail, Grace does not mention Maddock’s evocative nickname, ‘the Count of Monte Bello’, conferred for that famous countdown. ‘Maddock’s cool, calm voice crackled out over the radio every 30 seconds … For the last 30 seconds, the intervals between Maddock’s announcements shrank, and the tension increased exponentially: “25 … 20 … 15 … ten … five … four … three ... two … one … NOW”.’

The ‘NOW’ has a gut-punch. At that moment, the twenty-five-kiloton explosion (around 10kt larger than the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945) tore the Plym apart, spewed out radioactivity, gathered up the seawater all around and burst violently upwards. What then rained down on the men, the ships, the aircraft, the islands, and the mainland was as dangerous as it was downplayed by the authorities.

Sapper Fletcher on Zeebrugge described the scene: ‘It’s eight o’clock in the morning … sunlight, broad daylight, and the whole world just lit up. Double daylight, as you might say.’ Where Plym had been moored, the crater on the seabed was over 300 metres wide and six metres deep. The grotesque spectacle of dead sea creatures rising to the surface traumatised many present.

Grace is not without sympathy for the British scientists. ‘The British boffins were not stupid – they were quite brilliant in many ways – and they got a lot right. But they did not get everything right. They made lots of mistakes here and there, and being rather arrogant and obsessed with security, they responded by covering them up.’ This is a good summing up of all British atomic tests in Australia, which continued into the 1960s, mostly at Maralinga in South Australia.

Grace has a light, easy (sometimes laconic and vernacular-laden) storytelling style that gives sound and movement to the tale. His book is fast-paced and peppered with new and interesting information, with few missteps. He misnames the British committee called HUREX (Hurricane Executive) as Hurrex, and there is only passing mention of the shadowy figure who drove much of then Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s thinking at this time: Frederick Lindemann (Lord Cherwell).

But the politics is not really the point. This book is filled instead with the stories of the people who were present, whether as service personnel, scientists or journalists (always referred to as ‘press men’). Indeed, the book has a surprisingly exciting account of the work of the West Australian newspaper.

Also fascinating are stories of the long, squabble-ridden trip to Montebello aboard Campania. Hurricane technical director Leonard Tyte loathed the Task Force Commander, Admiral Arthur Torlesse, and their disputes deepened the divide between scientists and service personnel, with unfortunate consequences. Torlesse’s paranoia about any Australian, no matter how senior or security-cleared, is alarming as well as illuminating.

Grace declares at the start: ‘it became clear that if I wanted to read a full history of the operation from an Australian perspective, I would have to write it myself’. He has done just that, and thereby done his grandfather’s memory proud.

Comments powered by CComment