- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Custom Article Title: Two new books on the Tiwi Islands

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ripples of impact

- Article Subtitle: Two new books on the Tiwi Islands

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Just to north of Darwin is the country of the Tiwi people, spread over Bathurst and Melville Islands. These two new books give voice to Tiwi oral traditions and to the power and resonance within that tradition of orality that encompasses song, narrative, and the ways in which they sustain family and relationships to ancestors and to kin.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): John J. Bradley reviews two new books on the Tiwi Islands

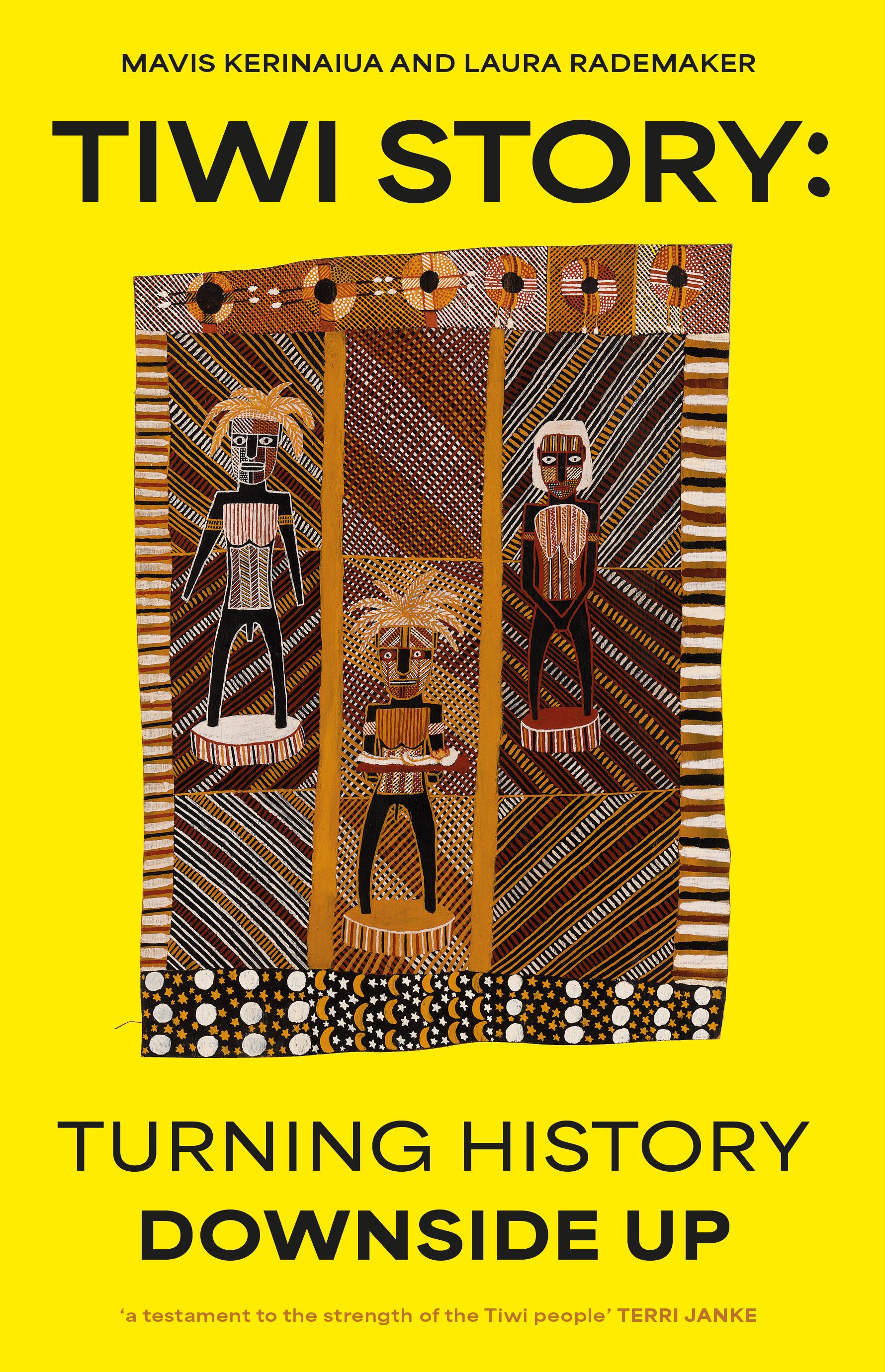

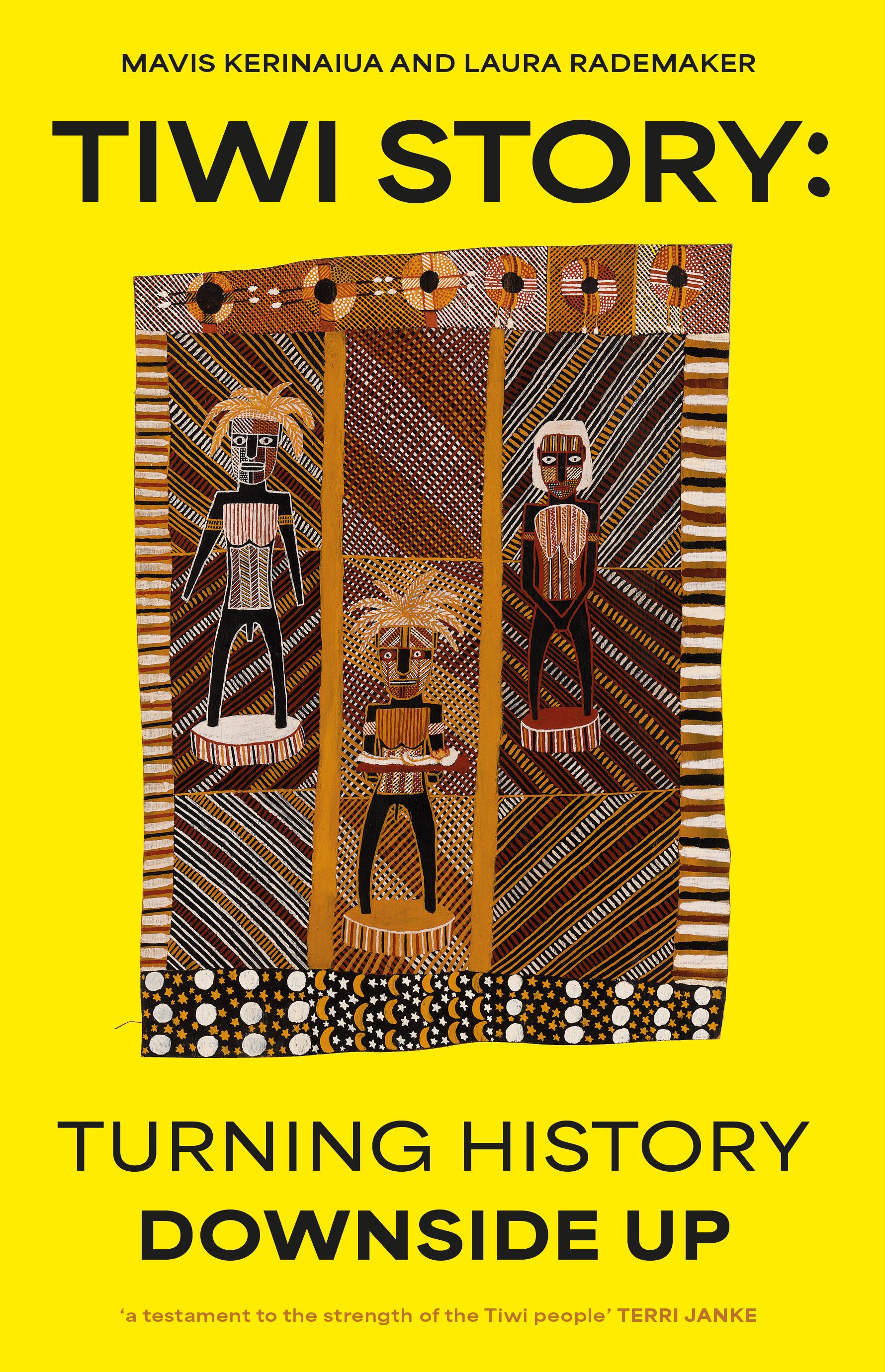

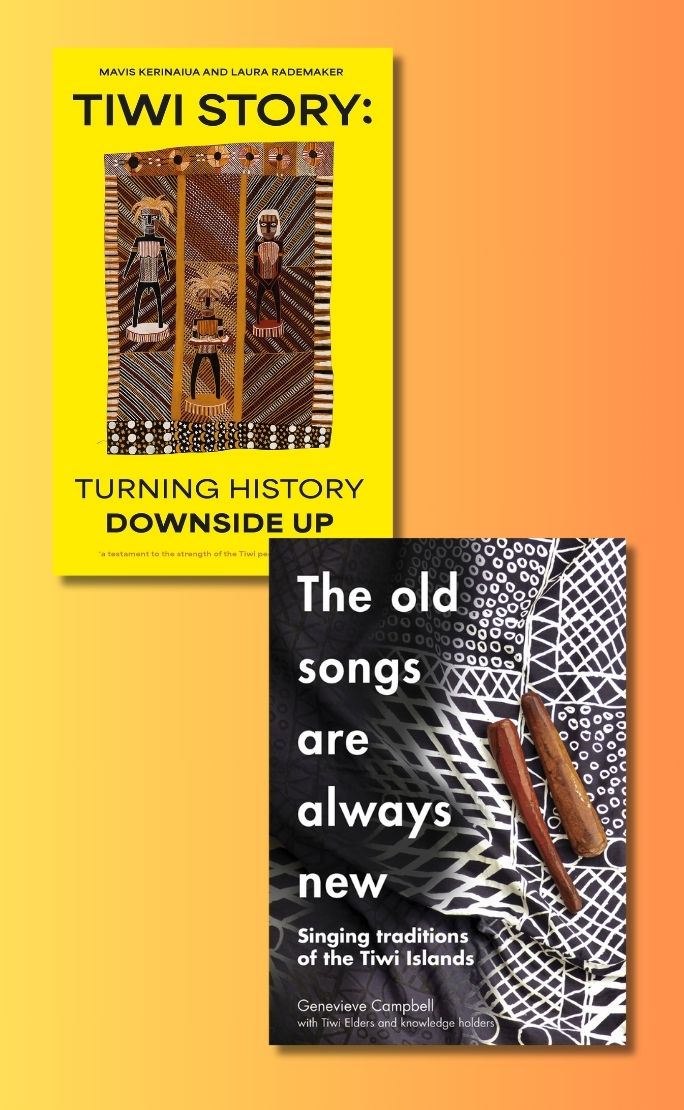

- Book 1 Title: Tiwi Story

- Book 1 Subtitle: Turning history downside up

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth, $39.99 pb, 209 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

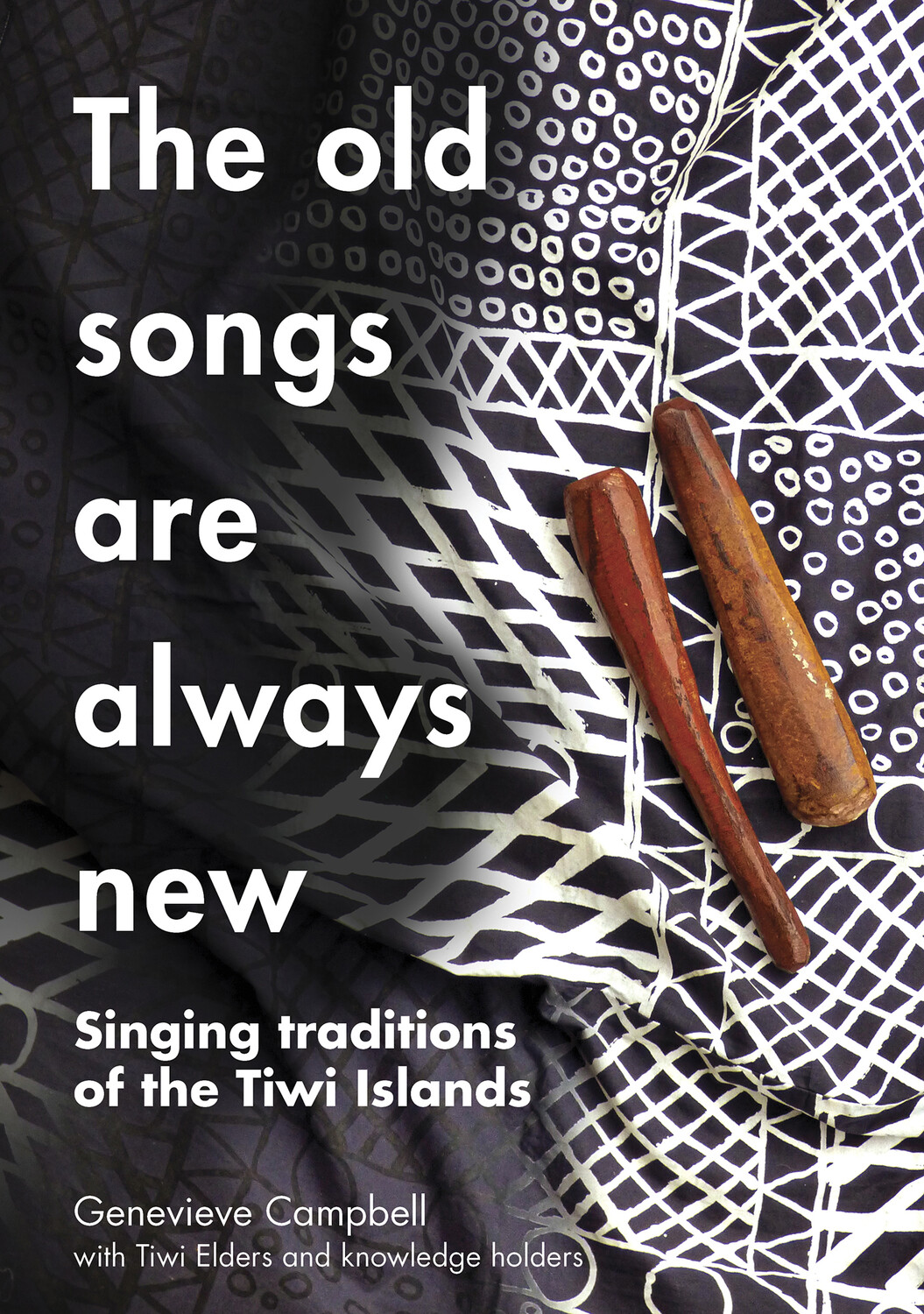

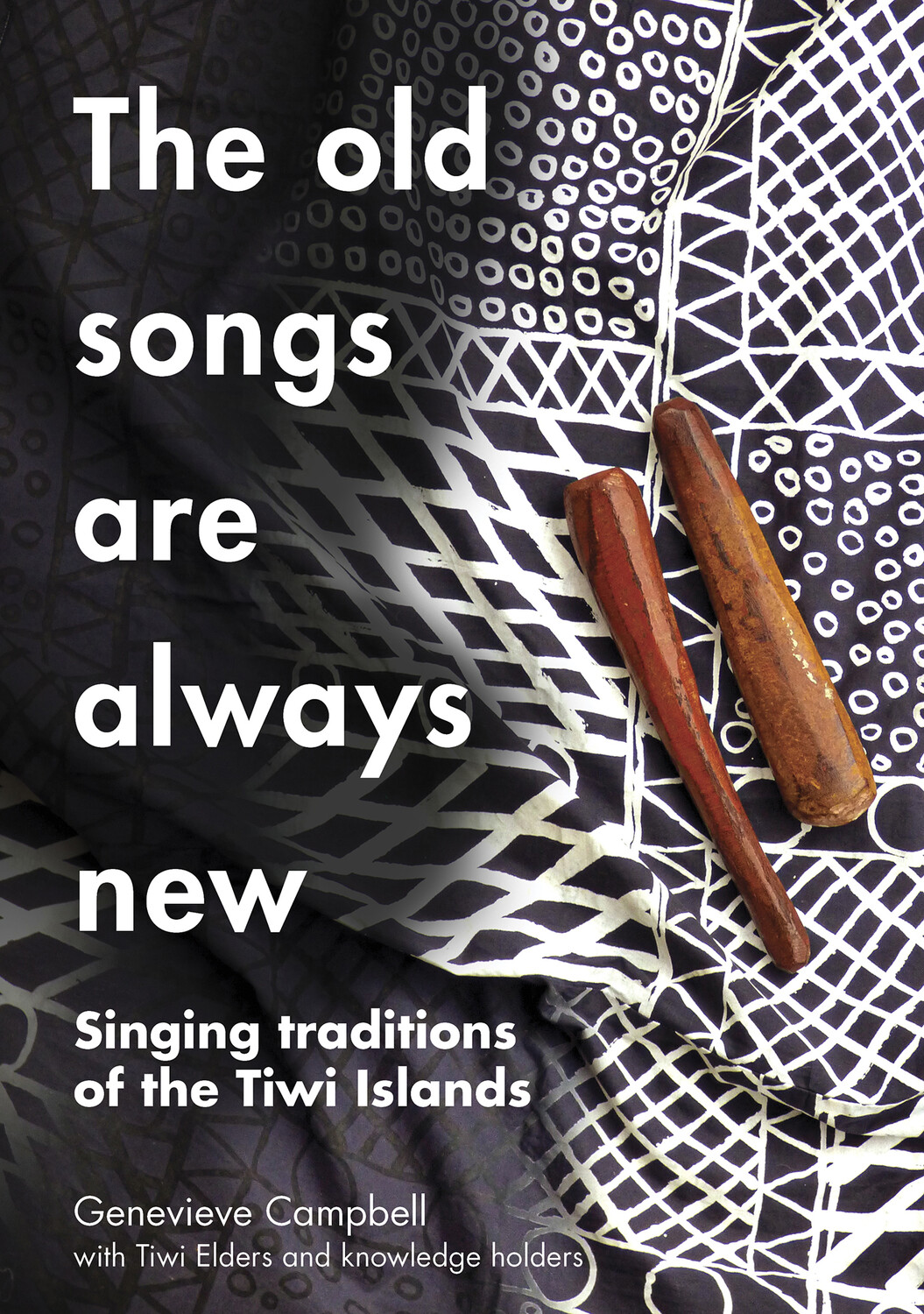

- Book 2 Title: The Old Songs Are Always New

- Book 2 Subtitle: Singing traditions of the Tiwi Islands

- Book 2 Biblio: Sydney University Press, $40 pb, 362 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Both books reveal clearly that despite the dominance of Western ways of knowing, of the power of Western historical positioning of music and narratives as the ultimate story, this has never actually been the case. For everything that has happened on the country of Indigenous people, there is always the version told or sung that is told by Indigenous people themselves – full of humour and pathos, sadness and grief – that never makes it into the ‘objective’ accounts of Western history. These books are primers that enable non-Indigenous readers to come to know how any one event can have another story, another way of it being interpreted.

These books also are also about colonisation. Read in a sensitive, nuanced, open manner, they show the reader that two things are going on. One is that the issues of colonisation dealt with in these books expose the forces of assimilation and suppression of Tiwi culture. The reader will also realise that to call Australia postcolonial is an oxymoronic term. Colonisation is not benign or static: it creates ongoing ripples of impact for Tiwi and other Indigenous cultures.

In these books, Tiwi storytellers and singers are placed at the centre of what is being committed to print. Consequently, the customary Western way of dealing with such stories as non-objective is completely bypassed. The Tiwi voices disrupt dominant Western notions of so-called intellectual rigour and legitimacy, and the reader discovers that Tiwi truth in these stories rests on an empowerment of their own understandings of worth, their own power in controlling situations that have never been acknowledged by Western historians. What is truth in these stories is a pre-colonial reality that Tiwi truth, if not all Indigenous truth, rests on the empowerment of Indigenous family, land, and sovereignty that needs no validation from colonial states or ideas of modernity.

Particularly telling in these books is the notion that any knowledge production is personal; that storytelling and singing is also agential and participatory. It becomes evident that the Tiwi singers and storytellers have never been silent in the face of colonial violence that attempted to subvert and neutralise forms of resistance. Far from being idle, the Tiwi have worked through their own understanding and participatory ways of sharing knowledge to sustain Indigenous ways of being and living. In this way, history is indeed is turned downside up; old songs are always new because the role of storyteller and singer is central to the exercise of agency and renewal; through the spoken and written word, they shape a particular view of the past for their communities. The stories, then, are not only about agency and the individual tellers: they are also communal sharings that bind communities together relationally, to family and Country.

The stories become a kind of medium for the Tiwi people to both analogise colonial violence and resist it in substantial ways. There is a kind of embodied reciprocity between the people and their stories and songs, so contrary to liberal notions of stories as some depoliticised acts of sharing. Both books demand that we recognise them as acts of creative rebellion; there is a decolonial agency going on in these texts that speaks to how the very acts of storytelling and singing imply breaking free from Western notions that stories are a kind of multicultural ‘show and tell’.

As with all cultures, the narrative and musical arts are sites of innovation, for taking a tradition and giving ‘it a twist’. This is an important factor considered: the place of song, history, and stories in a contemporary setting; the use of song and narrative, inspired by the past, can give voice to matters of the present. These discussions remove any lingering doubt that these books are just about ‘traditional’ forms. What is demonstrated is the way things from the past are made new, how other new things can then be created. There is a thread of commonality running through both these books, but this is also a source of tension. How does the past speak to the present, speak to future generations? What is the place of old ways of knowing the Tiwi language and a new way of knowing the language? Can one ever really create an archive of narratives that speaks to these understandings.

These are compelling questions that both books raise, they are important ones as Indigenous cultures and languages that still rely on the power of oral traditions come into contact with ideas and beliefs that somehow all things can and should be recorded, that somehow in this act of recording all things will be known and saved for the future.

These books speak so powerfully to the idea of words and music as living and creative acts. They are in part an archive of pain, suffering, and resistance, but in their telling they are also healing. Hearing them, reading them, allows us to reimagine the world.

Comments powered by CComment