- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Songlines in action

- Article Subtitle: Tracing five generations

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Reaching Through Time: Finding my family’s stories is the epitome of Indigenous family life writing. Predominantly set in New South Wales, on the east coast of Australia, Reaching Through Time is a journey through more than 200 years of Australian history, from early invasion and colonisation to the present day, through the lens of Indigenous family lived experience. This collection of life stories – skilfully located in the archives, family memory, and secondary sources – traces five generations of the authors’ family. Reaching Through Time is a rich, engaging contribution to Australian history. Bostock is writing against Australian historiography, which has excluded the voices of Indigenous families. As Shauna Bostock says: ‘This book is written for people who want to know our history from an Aboriginal perspective.’

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jacinta Walsh reviews 'Reaching Through Time: Finding my family’s stories' by Shauna Bostock

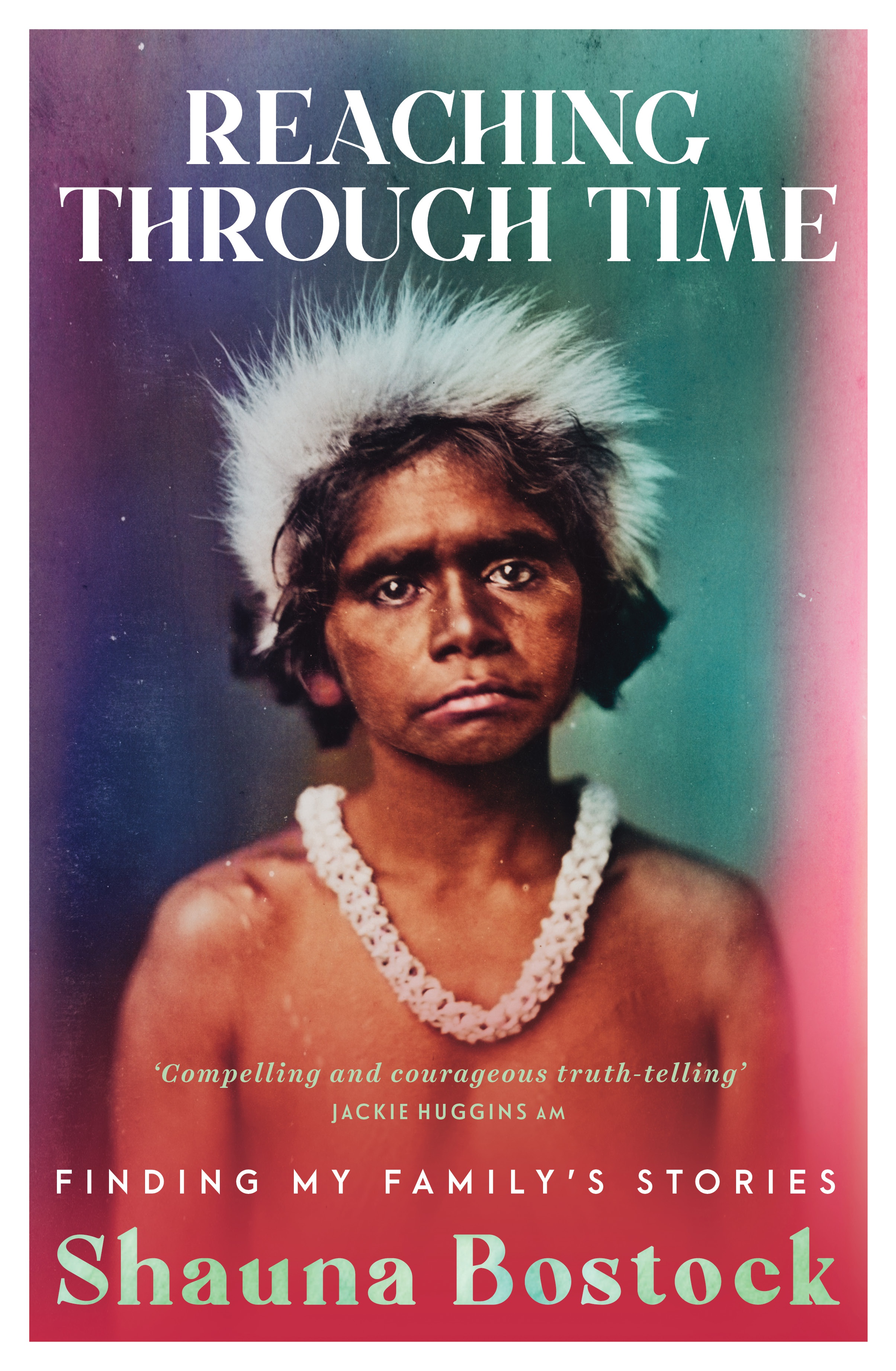

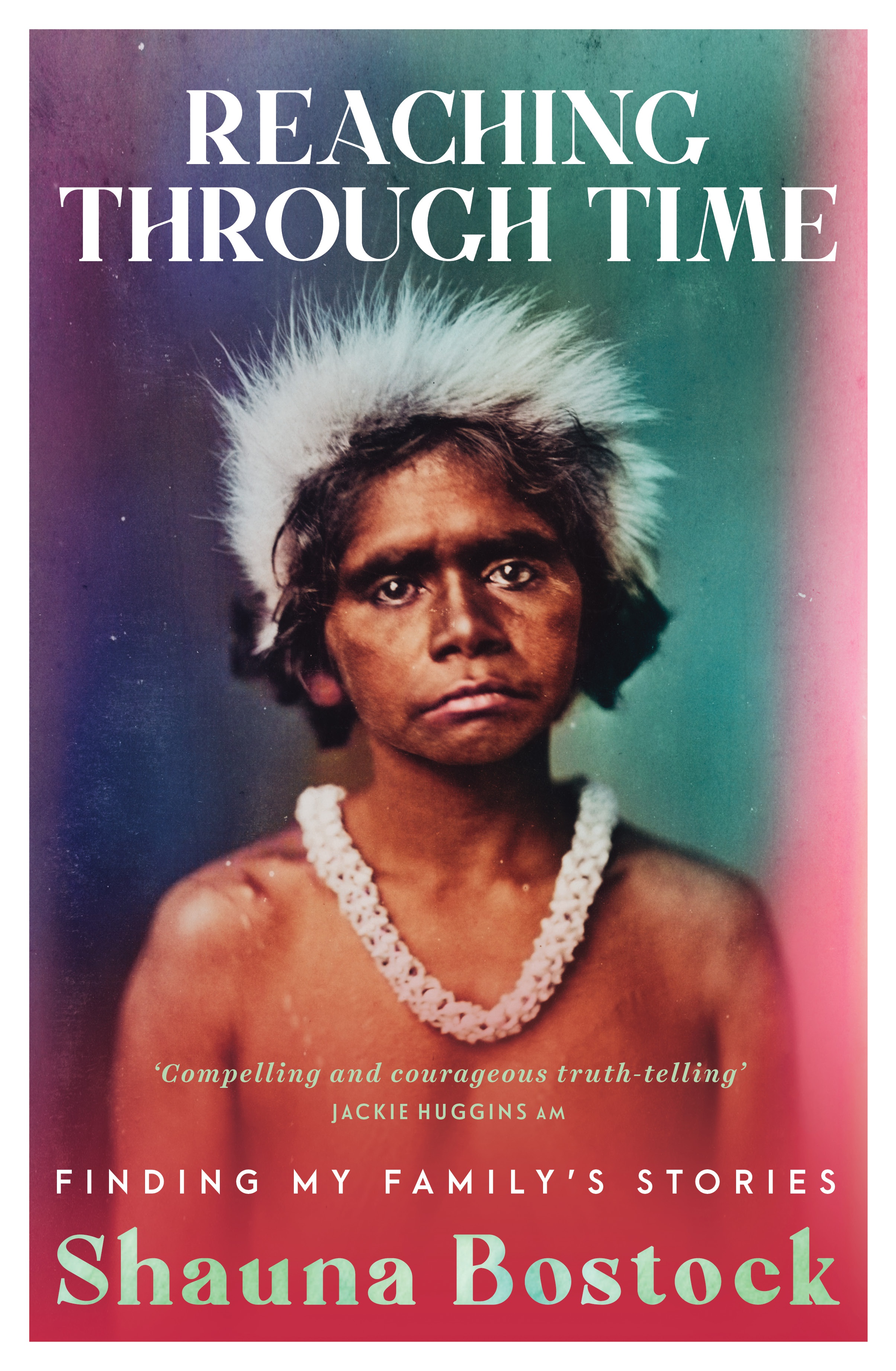

- Book 1 Title: Reaching Through Time

- Book 1 Subtitle: Finding my family's stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 347 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

This affirmation of cultural connection is an important assertion that despite the story of colonisation about to unfold, Spirit and Country for the Bostock family remains centre.

Bostock’s search for the truth begins with a phone call in 2008, revealing family ancestry links to the African slave trade in England from as early as the 1600s. She learns that her ancestor Robert Bostock, who arrived in Sydney in 1815, had been convicted of slave trading in Africa, and that his grandson Augustus John married Bostock’s great-great grandmother, a Bundjalung woman named ‘One My’. This is an ironically humorous start to an Indigenous family’s history.

Next, we are taken into the frontier violence and colonisation of Wollumbin/Mount Warning on Bundjalung Country in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We see the Land Act 1842 come into effect and white settlers like Bostock’s great-great-grandfather Augustus John Bostock applying for ‘Free selection’ land under conditional purchase. We see the arrival of gold prospectors and pastoralists in the early 1850s, the fencing of land, and the beginnings of the segregation of Aboriginal peoples. In the 1900s, we see the emergence of government policies designed to exclude Aboriginal people or to target and control them. We see the establishment of the ‘Board for the Protection of Aborigines’ in 1883, the introduction of the Apprentices Act 1901, the Neglected Children and Juvenile Offenders Act 1905, the Aborigines Protection Act 1909, and the Protection Amendment Act 1915, which collectively legislated the unpaid labour of Aboriginal people, the segregation of Aboriginal families, and the removal of Aboriginal children from their mothers.

Bostock shares family memories from the Kyogle Aboriginal station, the Box Ridge Reserve, the Dunoon Aborigines Reserve, the Nymboida Aborigines Reserve, and the Ukerebagh Island Aborigines Reserve. We see how families moved from one reserve to another to escape the reach of the Aborigines Protection Board’s control. Bostock honours family members who, over generations, served in the Australian military forces, and who were excluded from mainstream war entitlements.

After the 1967 referendum, Bostock notes the movement of thousands of Aboriginal families to the inner city of Sydney in the 1960s and 1970s, and with it the rise of Aboriginal family activism. There is the formation of the Aboriginal Australian Fellowship, the Foundation of Aboriginal Affairs (FAA) and the Redfern Aboriginal Legal Service, the first free legal aid service in Australia. We are given a window into the creation of the Tent Embassy in 1972. We witness the rise of ‘Blak’ Theatre movements in Melbourne and Sydney and subsequent Indigenous community artistry, cultural expression, and political activism.

Through all of this storytelling, the names of many Indigenous and non-Indigenous family members and research collaborators are honoured. Bostock knows that there is agency in a name. In the textual records created in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the names of Aboriginal people are often incorrectly noted, changed through time, or omitted altogether. Grand Australian narratives have historically failed to name, honour, and celebrate Aboriginal people individually. Bostock’s storytelling provides a correction to this erasure. She says:

Family history research is in fact a way to counteract my Aboriginal ancestors’ erasure; its enabled me to pull them out of the collective noun ‘the Aborigines’ used by white Australian’s and restore their individual humanity. Its deep, heartfelt, spiritual resurrection.

Reading how Bostock has located and pieced together this complex web of family stories is as interesting as the stories themselves. The complexity in Bostock’s narrative correlates with her access to and forensic analysis of family oral histories, historical textual records, and the scholarship of others. Bostock shares her insights into the challenges she and many other Indigenous families face in gaining access, in particular, to the textual records created and held by state organisations. Bostock calls out the systems that deny Aboriginal families their access to all the records that are about them or relate to them. I commend Bostock for utilising her voice to bring public attention to this important issue; archival access and cultural safety for Aboriginal families.

What a joy and a privilege it was to read and review this book. Bostock’s storytelling is engaging and compassionate. She has invited us into her family’s conversations and into the kitchens and loungerooms of her family’s homes. This is Songlines in action, Songlines through storytelling. Bostock brings history alive, for generations to cherish.

Shauna Bostock is one of many Indigenous scholars who, for decades now, have emerged as a formidable force in Australian history making. Writers such as John Maynard, Jackie Huggins, Stephen Kinnane, Natalie Harkin, Faye Blanch, Tony Birch, Lynette Russell, Cindy Solonec, Betty Lockyer, Debra Dank, Elfie Shiosaki, Aileen Marwung Walsh and Judi Wickes have blazed their way in Australian historiography. They are smashing apart old and outdated homogenous and nameless misrepresentations of Aboriginal people and their families, creating new truths, and enabling processes of reconciliation and healing.

Bostock jokes that her family is like the ‘Forrest Gumps’ of blackfellas. They certainly are for the Bundjalung mob, at least. For any Indigenous community members who are fortunate to read this book, I hope it serves to encourage them, too, to be the ‘Forrest Gump’ storytellers for their mobs; to ensure that individually and collectively we represent the diversity that exists within the lived experiences of Australia’s First Nations peoples.

Comments powered by CComment