- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A race against time

- Article Subtitle: A memoir that bears witness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

'Not everyone wants to hear about the Holocaust. It’s easier to read Anne’s diary.’ As a survivor of the Shoah, Hannah Pick-Goslar was acutely aware of this piteous truth. She made the statement during a 1998 interview marking the release of a children’s book about her close friendship with Anne Frank and her own remarkable survival. For the countless readers familiar with Frank’s diary, Hannah (referred to as Lies, a pseudonym linked to her nickname) is a recurring presence. There are diary entries in which a distressed Anne, rightly assuming that Hannah is not in hiding, beseeches God to watch over her friend so that she may live to the end of the war. In history and this book’s wake, these passages are rendered even more bitterly tragic.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tali Lavi reviews 'My Friend Anne Frank' by Hannah Pick-Goslar with Dina Kraft

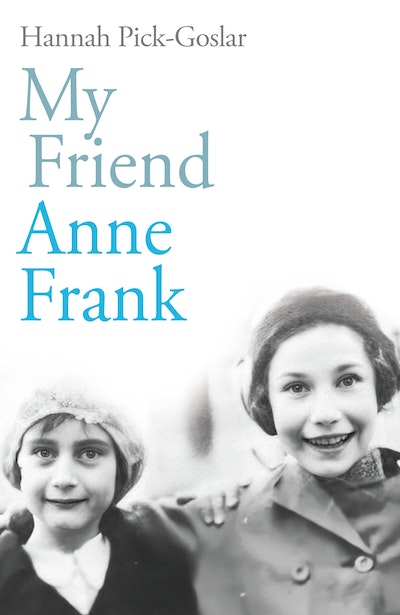

- Book 1 Title: My Friend Anne Frank

- Book 1 Biblio: Ebury Publishing, $35 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the afterword, Kraft characterises the writing process as being one of a ‘race against time’. She began interviewing Hannah, who was then ninety-three, in her Jerusalem apartment in 2022. The writer describes her as ‘still razor sharp of mind but increasingly frail of body’. Hannah died six months later. Fortunately for Kraft, there was a considerable amount of primary evidence to rely upon, including Hannah’s numerous past interviews, surviving letters, telegrams, a family album, other testimonies, and further historical texts. The sense of compression in the book’s production is evident in several places.

For the most part, the memoir has an assured tone. The prologue, however, falters. Narrated by Hannah’s older self, it attempts to set up the book’s framing device – an uneasy one – by making connections between her visiting great-granddaughter and her child self who was ‘only a little older’ when she first met Anne. The ensuing chapter ‘Berlin’ thankfully moves into a different register. From this point on, the voice is anchored in the embodied child experience, but also employs a knowing voice that deftly shifts between tenses amid a deeper, historical narrative. Significantly, it belongs to its true subject: Hannah Pick-Goslar.

Hannah’s heritage is deeply rooted in the Jewish German experience. Kraft acknowledges Amos Elon’s The Pity of It All: A portrait of the German-Jewish epoch 1743–1933, and it is clear why. Hannah is only five years old when Hitler attains power – the endpoint of Elon’s masterful work – but her family had made Germany their home for more than a thousand years: ‘Our home bridged German philosophy and literature with Jewish tradition.’ Her parents, Ruth and Hans Goslar, both singularly beloved, were dedicated to lives thrumming with ideas, culture, and principles of humanism, and instilled these values in their eldest daughter. Evidence of this is found throughout her life. Interested readers will be rewarded by further research into the backgrounds of individuals mentioned. Several are noteworthy for their cultural or pedagogical achievements (e.g. Dr Albert Lewkowitz, Clara Asscher-Pinkhov, and Hans Kreig); others (such as Otto and Hennie Birnbaum) for their astonishing deeds.

Hannah’s father, Hans, a talented communicator and head of the press office, was ‘one of the highest ranking Jewish officials’ in the Weimar Republic. Hans was also an influential community leader who, despite having grown up in an assimilated family, became religiously observant. His religious fidelity had a lasting impact upon Hannah. This distinctive perspective – of being intimate with both the dominant culture and part of the religious community – forms a vital, compelling impression of life across both worlds during wartime.

The book is distinguished by a robust morality. This is manifest in Hannah’s assiduousness regarding historic detail and a commitment to the ideal of generosity. When it comes to the latter, she is equally influenced by both parents. But it is her father’s good deeds in Berlin, later in Amsterdam – where he sets up a refugee relief agency in their small apartment – and also in the camps, which affect her in critical ways.

At the age of thirteen, Hannah becomes a maternal figure to her two-year-old sister Gabi after Ruth’s tragic death. Later, at Westerbork, she is a compassionate carer of young children in the orphanage run by the Birnbaums and we are devastated beside her as she bears witness to their deportation to Auschwitz. Her unfaltering love and commitment to her younger sister animates her, despite the increasingly harrowing conditions of Bergen-Belsen: ‘For me, there was no time to contemplate not surviving. As always, I had to keep Gabi alive.’ There are countless instances of other people’s radical acts of humanity, especially among the women in her barracks in Bergen-Belsen. Hannah’s propensity to name many of them signifies her determination to ensure something of their memory endures. Their actions are revolutionary counterpoints to the acts of mindless and conscious cruelty perpetrated by the Nazis and their accomplices. Hannah’s decision to train as a children’s nurse after the war and her work among vulnerable communities are shaped by these same humane principles.

Apathy is this book’s haunting. In Bergen-Belsen, Hannah witnesses it as a terrible consequence of the systematic dehumanisation, starvation, and torture of her people. Once women, men, and children succumb to apathy, they are unable to continue living. She witnesses it, too, in the peering faces of people from her neighbourhood as she and her family are deported from their homes. Apathy is also present in the refusal of governments to grant refuge to desperate families and communities. Hannah was similarly committed to Elie Wiesel’s scorching pursuit, ‘For the dead and the living, we must bear witness.’ It was a pursuit bound up with carrying forth the memory of her family, of Anne, of the overwhelming countless others who perished, of history. It is up to us then, the living, what we do with Hannah’s story. Let’s begin by calling it by its rightful name.

Comments powered by CComment