- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fabergé egg

- Article Subtitle: A glittering portrait of a cosmetics empress

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Angus Trumble, who died suddenly last October, was a towering figure with a slight sideways tilt to his head. In his famously dandyish attire he might have stepped out of a Max Beerbohm cartoon, and appropriately so given his expertise in Victorian and Edwardian art. Trumble’s latest, and last, subject also chimes with one of Beerbohm’s earliest literary ventures, ‘A Defence of Cosmetics’, published in 1894.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ian Britain reviews 'Helena Rubinstein: The Australian Years' by Angus Trumble

- Book 1 Title: Helena Rubinstein

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Australia years

- Book 1 Biblio: La Trobe University Press, $34.99 pb, 286 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

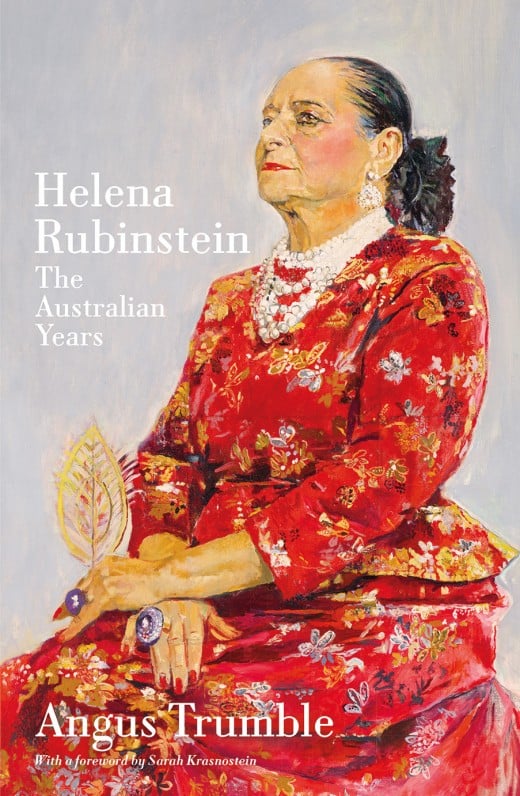

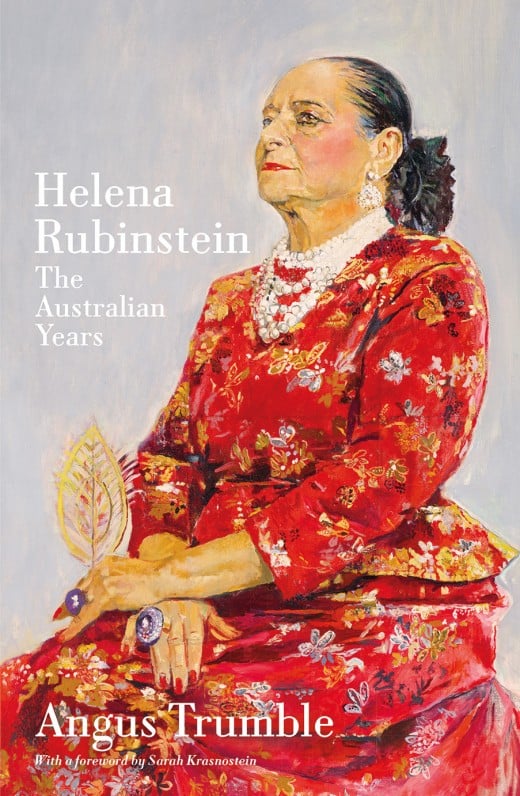

Helena’s, you might say, were the facial products that launched a thousand shops: a network of swanky beauty parlours in glamorous metropolitan capitals far from Australia and specialty counters in department stores or chemist outlets across the Western world. While tiny in physical stature, she came to tower above most of her commercial competitors, partly through her creation of a distinctive aesthetic ambience or mystique in all of her so-called salons. She also established a niche in the circles – salons of a more culturally rarefied kind – of some of the twentieth-century’s most illustrious artists. Among those who made portraits of her, in various media, were Picasso, Dalí, and Dufy in Europe, Andy Warhol in America, William Dobell in Australia, Cecil Beaton and Graham Sutherland in England.

It was one of Sutherland’s paintings of her, Helena Rubinstein in A Red Brocade Balenciaga Gown (1957), that Trumble managed to acquire for the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra when he was director there between 2014 and 2018, and that inspired him to set off on his biographical quest. It’s her formative Australian connections, inaccurately represented in her own accounts of her life and by previous biographers, that provide the chief focus of Trumble’s impressive investigations, but his study of her personality and career is much more wide-ranging than that. One wonders, indeed, should he have lived to see the book through to publication, whether he would have been content with the subtitle it’s ended up with: The Australian Years. As well as giving a limited sense of the book’s geographical, chronological, and thematic reach, it’s rather bland, and hardly worthy of the wit and elegance and brio of so much of the writing.

There are, it has to be said, some rather labyrinthine passages in Trumble’s text where he seems to get carried away with his intricate detective work at the expense of narrative fluency. But then – and most notably in recounting his subject’s pre- or post-Australian years – there are some grand and dazzling set pieces. His vignettes of the ‘exotic ports’ of call on her first voyage out from Europe are among the most exquisite specimens of travel writing I know. Could there be a richer evocation of Aden than his conjuring of this ‘hot dry mythic world of Arabia’, with ‘the scent of coffee and black pepper in the old spice market, the upward lurch and roaring of the camels, the angular profile of Yemeni fishermen’s transom-sterned elbows’?

A more fitting title for Trumble’s study – signalling its true scope as well as matching the playfulness of an earlier title of his, The Finger: A handbook (2010) – might have been ‘Helena Rubinstein: Her Make-Up’. There’s a good cue for this in the paean he quotes of Graeme Sutherland’s: ‘her make-up is sensational’. That’s referring, of course, to her personal self-adornment when the portrait painter first encountered her in the flesh, but the term ‘make up’ (with or without the hyphen) could be stretched to several other aspects of her that Trumble covers in his pages: the nature of all her commercial products, the constituents of her psychology – her ruthlessly shrewd business instincts and seeming obliviousness of risk – and the degree of sheer fabrication in her self-representations and the promotion of her wares. Her trail-blazing ‘skin food’, Valaze, did not, as she asserted, come from her connections in Europe with its putative formulator, Dr Lykuski, and his recipe of rare herbs from the Carpathian mountains; she just brazenly invented all of that, hiding its true origins as a lanolin-based substance derived from Aussie sheep, laced with bleach. It was a concoction in more than one sense, its purported natural qualities entirely made up along with its faintly Gothic back story. (The legendary Dr Lykuski sounds like a character Boris Karloff might have played.)

Trumble’s book is let down by its publisher in other ways. It is most commendable that it’s been enabled to come out at all when its author is no longer around to promote it, but, apart from a striking front cover (a reproduction of the Sutherland portrait), the production values are lacklustre when they should have been lavish. Helena Rubinstein, in all her outrageous flamboyance, and Trumble in his, deserve better than the format of an academic monograph with washed-out black and white photographs on matte-finish paper, small-scale colour reproductions clustered in the centre instead of appropriately disposed throughout the text, and endnotes without running heads of the page numbers to which they correspond. Maybe this is asking too much of the publishing industry in straitened times, but I can’t help feeling that Trumble’s work could catch the eye and tempt the purse of many more prospective book-buyers if given the glossy look and generous dimensions of a regular art book. As Trumble conveys, Helena Rubinstein was in her way something of an artist herself, as well as an artistic inspiration and a superlative con artist.

It would be overstating this book’s flaws and deficiencies to call it a curate’s egg. The text, at least, in its bejewelled multi-facetedness, is more the verbal equivalent of a Fabergé egg. It just cries out for a design to match.

Comments powered by CComment