- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: The Melbourne Dictionary People

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Melbourne Dictionary People

- Article Subtitle: Active service to the mother tongue

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There are many impressive things about the first edition of The Oxford English Dictionary (OED), but one in particular has long puzzled me. As an Australian, I have always been struck by its excellent coverage of Australian words. I am not talking about the inclusion of obvious words such as kookaburra, woomera, and fossick, but rather the hundreds of lesser-known words such as wonga-wonga (pigeon), wurley (hut), and yarran (species of acacia), and even more obscure ones such as brickfielder, defined as a ‘local name in Sydney, New South Wales, for a thick cloud of dust brought over the city by a south wind from neighbouring sandhills (called the ‘Brickfields’)’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Sarah Ogilvie on Australia in the Oxford English Dictionary

But who were all those people who responded to Murray’s call and, especially, who were the Australians?

Eight years ago, while exploring the OED archives, I made a dramatic discovery. In a hidden corner of the Oxford University Press basement where the dictionary’s archive is stored, I lifted the lid of a dusty box and found a small black book tied with cream ribbon. Opening the book, I immediately recognised Murray’s immaculate handwriting. It was his address book recording the names and addresses of, not hundreds, but thousands of people who had volunteered to contribute to the dictionary. I soon discovered two more of his address books and three further address books belonging to the previous editor, Frederick Furnivall.

Over the past few years, I have pored over these six address books, researching the people listed inside them – where they lived, what they did with their lives, whom they loved, the books they read, and the words they contributed to the dictionary. Some people have remained mysteries to me, despite my trawling through censuses, marriage registers, birth certificates, and official records, but most have come to life with such force it is as though they have been calling out for attention for years.

There were people from all around the world and all walks of life – a pornography collector in London, a murderer in California, a chaplain in the goldfields of New Zealand, an anti-slavery activist in Philadelphia, a missionary in the Congo, a journalist in Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the inventor of the tennis net adjuster in Yorkshire, an aunt and niece who happened to be lesbian lovers, and a cocaine addict found dead in the lavatory of a railway station.

And then there were the Australians!

The address books and a great deal of extra detective work led me to a small group of men living in Melbourne in the late nineteenth century. They worked first at Melbourne Grammar School and then all gradually moved to the University of Melbourne. They were an impressive group of academics: Edward Sugden, Master of Queen’s College; Edward Hippius Bromby, University Librarian; Alexander Leeper, Warden of Trinity College; Richard Elliott, Classical Lecturer at Trinity College; and Edward Ellis Morris, Professor of Modern Languages and Literatures.

I dubbed them the Melbourne Dictionary People. All of them had been born and educated in Britain, and most attended Oxford. Once they had moved to Melbourne, they formed a tight network, exercising patronage for one another, demonstrating how élite British expats tended to negotiate and maintain power in a new colony. It was a dynamic but contentious group of men. I hesitate to call them friends, because most of them fell out and ended up bitter enemies, as described by John Poynter in his wonderful book Doubts and Certainties (1997).

Sugden had been volunteering for Murray’s dictionary for many years before leaving England. Elliott had studied and lived in Oxford and was also known to Murray. The others may have learnt about the project from these two men, or they may have responded directly to one of Murray’s appeals for volunteers. What we do know is that they all ended up working together, gathering quotations and words unique to Australia and New Zealand, and sending them to Murray in Oxford.

By writing to newspapers and giving lectures around Australia, they recruited others to join them in this word collection. In a letter to The Argus newspaper in 1890, Elliott appealed to Australian patriotism:

Dr Murray asked me to point out to Australians that while he had received much enthusiastic help from many Americans, he had hitherto received very little indeed from Australians, and that, consequently, Australian words and usages must be very scantily represented, unless he receives more help from Australians in the shape of illustrative quotations, especially of the earliest instances in Australian newspapers and books.

At the centre of this group was Morris, who became an obsessive word collector and travelled around the country advocating for the OED. ‘Something has been done in Melbourne,’ he told a gathering in Tasmania in 1892, ‘but the Colonies have different words and uses of words, and this work is of a kind which might well extend beyond the bounds of a single city.’ He made a rousing appeal to his listeners: ‘Twenty or thirty men and women, each undertaking to read certain books with the new dictionary in mind, and to note in a prescribed fashion what is peculiar, could accomplish all that is needed.’ This drive for help was hugely successful and more than two hundred people volunteered from around Australia, and many also in New Zealand.

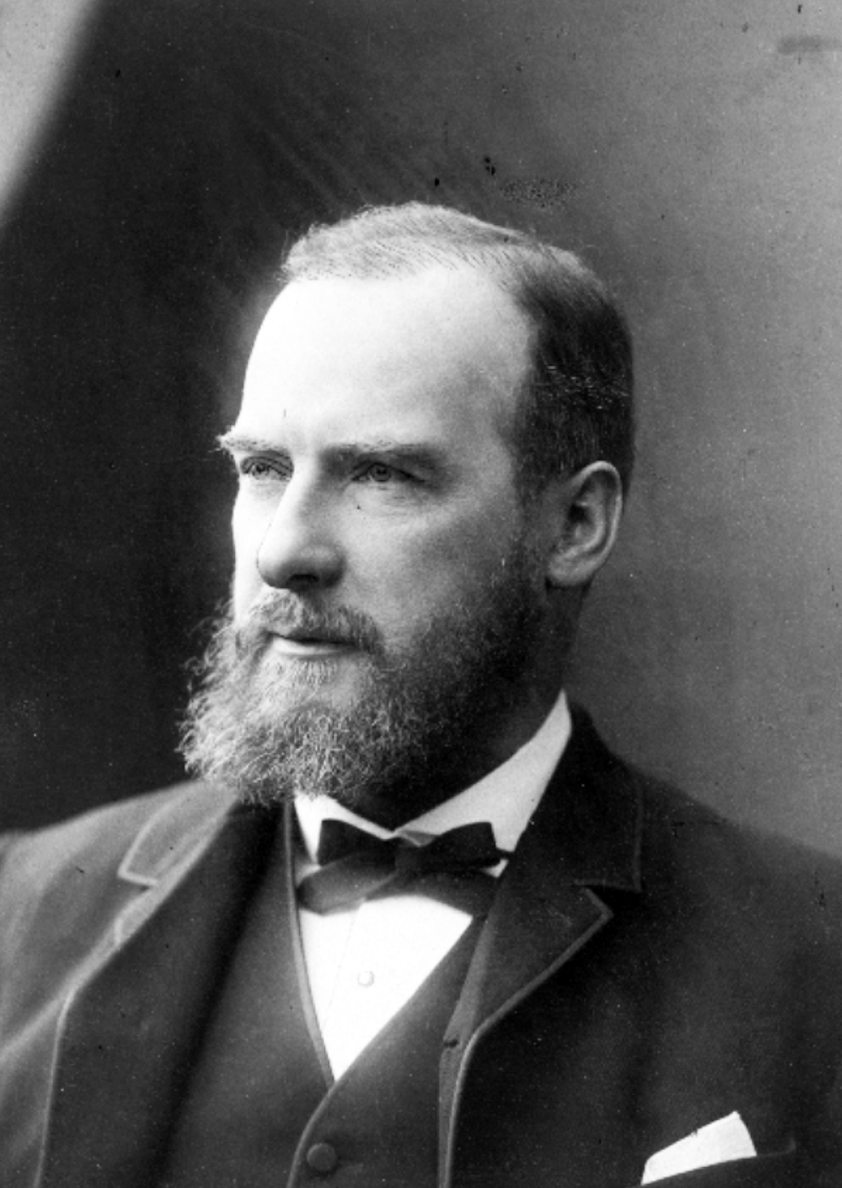

Edward Ellis Morris (image supplied by the author, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria)

Edward Ellis Morris (image supplied by the author, courtesy of the State Library of Victoria)

After a few years, Morris decided it was time to create his own dictionary. He harnessed assistance from a loyal group of specialists whom he knew from the University of Melbourne, where they had either studied or worked: experts on Australian botany, Baron von Mueller and Johann G. Luehmann; museum director Sir Frederick McCoy; the anthropologist and natural scientist Alfred W. Howitt; anthropologist Baldwin Spencer; bird specialist Alfred J. North in Sydney; biologist Thomas Sergeant Hall; naturalist Joseph J. Fletcher; and Aboriginal languages expert, the Reverend John Mathew of Coburg.

Morris became the Australian Murray. He copied Murray’s lexicographic policies and practices and built up a faithful network of volunteers and advisers. In 1898, he published Austral English: A dictionary of Australasian words, phrases and usages. It was an Australian version of the OED, each entry with dated citations showing the word’s usage across time. Morris had created Australia’s first historical dictionary, a superb record of Australian and New Zealand English in the nineteenth century. He deserved more praise than he received, and the dictionary deserves to be better known than it is, although he was awarded a Doctor of Letters from Melbourne University.

The Melbourne Dictionary People were not typical of the OED volunteers: they were all male, and they were specialists, academics, and experts. Most of the other volunteers were, by contrast, amateurs, often autodidacts, and included far more women than we might expect. Their contribution to a scholarly enterprise at a time when access to higher education was limited to the élite meant that they had a tie to a prestigious scholarly project. For the Melbourne Dictionary People, who were part of the academic world, the appeal for them may have been the nostalgic link it gave them to their homeland, as well as the chance to prove their loyalty, through scholarship, to their adopted country.

The Melbourne Dictionary People formed just one small group of the three thousand volunteers who made the OED. They joined with hundreds of Americans; a disproportionate number of ‘lunatics’ (as they were described in the censuses) contributing detailed and rigorous work from psychiatric hospitals; families reading together by the gas light to send in quotations; and numerous others, from vegetarian vicars to suffragists.

The contribution of the Australians to the OED is more than just the story of Empire in active service to the mother tongue. It is the story of faithful and loyal volunteers who took up the invitation to read their local books and help describe their local words so that the bounds of the English language would not only be expanded but also recorded for future generations.

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment