- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Three novels about artists and their subjects

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: What artists do

- Article Subtitle: Three novels about artists and their subjects

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The relationship between artists and their sitters has long been a topic of fascination and enquiry – not least for artists themselves. The study of portraiture is often informed by investigations of this relationship as well as that with a third party: the viewer.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Naama Grey-Smith reviews three novels about artists and their subjects

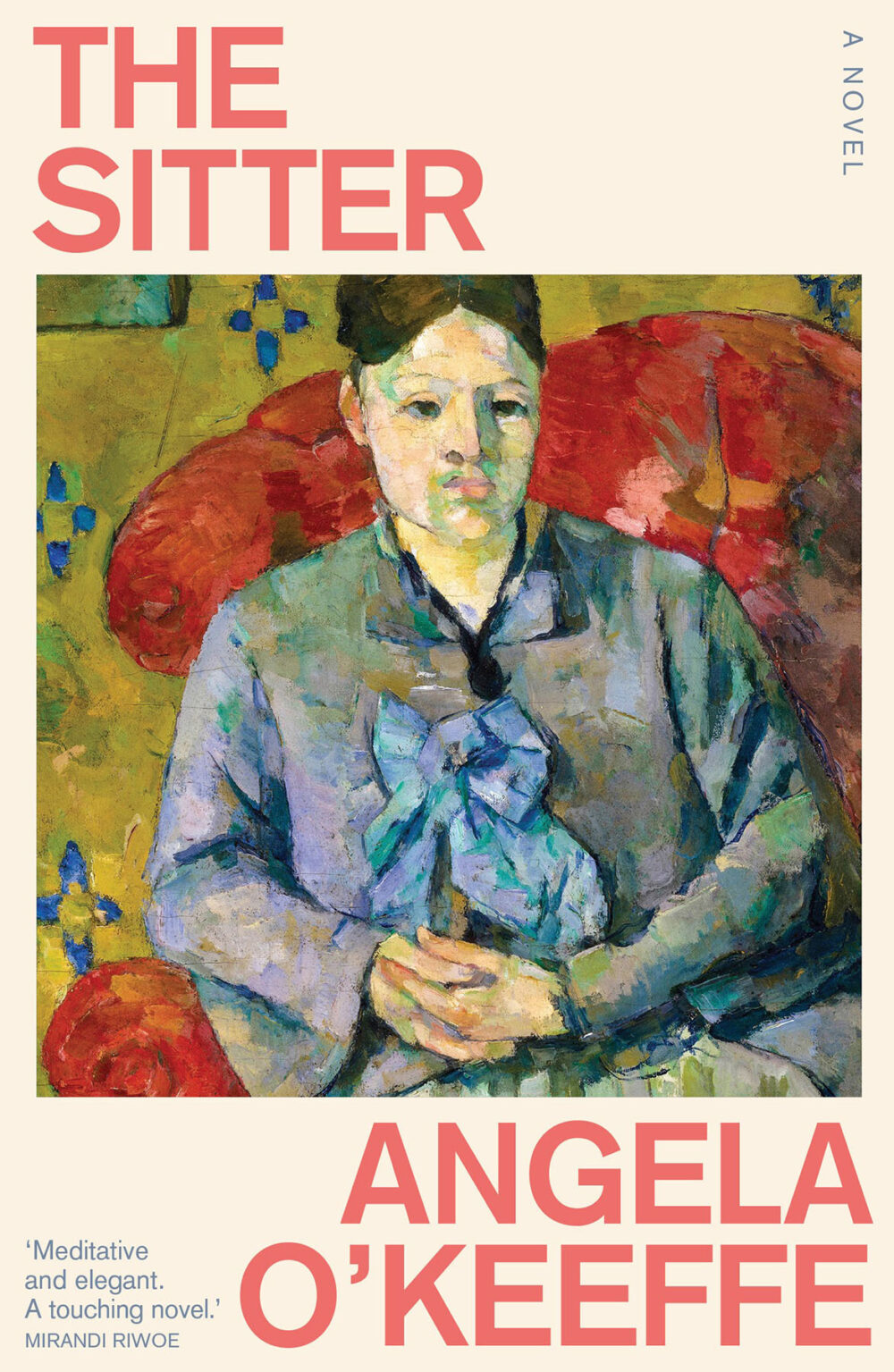

- Book 1 Title: The Sitter

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.99 pb, 180 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

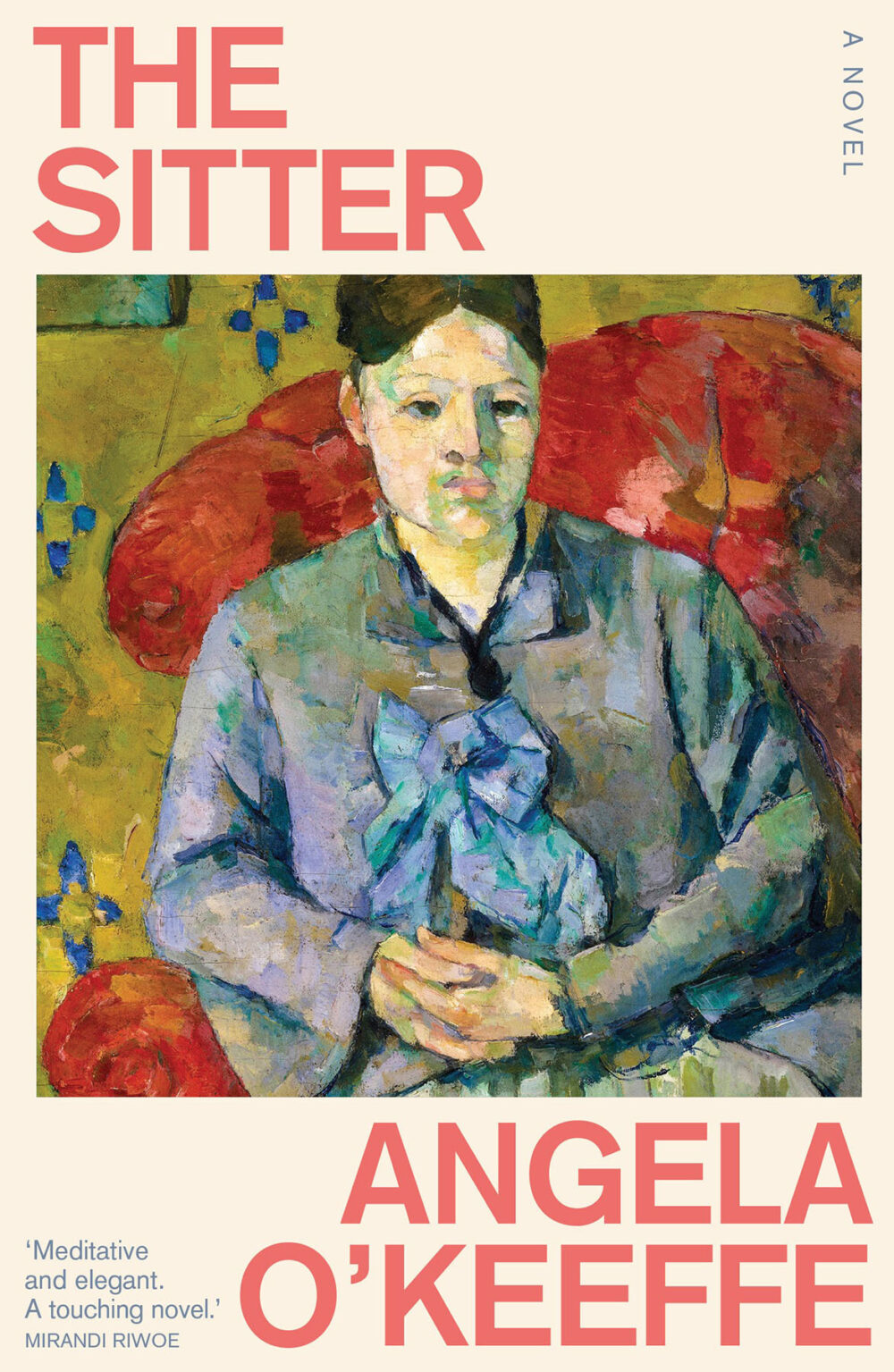

- Book 2 Title: Vincent & Sien

- Book 2 Biblio: Macmillan, $34.99 pb, 326 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Wall

- Book 3 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $29.95 pb, 220 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The second part, which centres on the writer’s past, is especially successful. Here, O’Keeffe imbues the writing with dreamlike qualities: condensation of characters, uncountable brothers who multiply and contract, the mother as a character willing to live on the page. Recurring motifs abound: ‘the story is a circle,’ says the writer.

Stylistically, the writing never becomes quite as strange as this concept promises; I wished at times that the author would trust the reader’s ability to make meaning. For example, the poignant image of dingoes howling, each ‘a lone voice calling through the darkness’, is robbed of its power when, on the next page, the narrator spells out: ‘We are like the dingoes, calling to one another while standing close’. The prose tends towards figurative language, especially personification (‘the air holds a breath of warmth’), combined with an almost aphoristic lilt (‘Perhaps the child merely runs; perhaps running is what the child is’).

Ultimately, the book’s energy is with the writer’s tale. The significance of Hortense’s biographical offerings is not always established, especially in the final part. However, as O’Keeffe sensitively and persuasively conveys, the writer’s well-realised story would not be possible were it not for her pursuit of Hortense’s, for ‘there was a kind of porousness between us, when I looked at her, and she looked at me’.

Another famous sitter, Sien Hoornik, is given a voice in Silvia Kwon’s Vincent & Sien (Macmillan, $34.99 pb, 326 pp). Hoornik was one of Vincent van Gogh’s early sitters, and the only lover he lived with. Van Gogh had met a pregnant and sick Hoornik in 1882 on the streets of The Hague, where she worked as a ‘prostitute’, and took her into his studio. The fate of their relationship – or, given that the artist’s suicide is well known, the reasons for that fate – drives the narrative in this eminently readable historical novel.

Besides a short section narrated by Vincent’s brother Theo, the novel is told from Hoornik’s point of view, richly imagining van Gogh’s familiar story through the intimate and often critical gaze of a woman outside his social class. With a blurb that invokes the full panoply of van Gogh conventions – ‘a struggling artist’, his ‘muse’, the ‘road to artistic genius’ – the novel does not so much subvert the common perception of van Gogh as enliven it. This it does assuredly and convincingly.

Especially well rendered is Sien and Vincent’s bond as misfits. ‘Oh what a delightful painting of the Scheveningen baths. We holiday there every summer’, Vincent imitates the wealthy patrons who overlook his work. For Sien, ‘That he should see them with the eyes of her own tribe reassures her that he does not quite belong to them.’ Vincent similarly mocks his art dealer uncle, whose ‘idea of a beautiful painting is Phryne Before the Areopagus by Gérôme’ – a ‘prostitute from classical Greece’ with ‘not one single strand [of hair] on her entire body. Her skin is purer than marble. You get the idea.’

Sien’s doubt-versus-hope pendulum as the pair battle domestic strife, societal norms, and filial expectations grows tedious, but Kwon’s skilful characterisation and witty observations keep the reader engaged. When Vincent finds a crate for Sien to sit on at a clinic, she is startled: ‘Is this what artists do? Make a fuss?’ Facetious, but she has a point. Artists see. And, as Vincent tells Sien about the downtrodden figures he draws, ‘it’s more than just seeing; I have to express what they do to me.’

Though similarly concerned with expression, Wall by Jen Craig (Puncher & Wattmann, $29.95 pb, 220 pp) is a story of quite a different kind. Here, subjects are never as important as objects (though the two are inextricably entangled). The narrator is a London-based artist who, on returning to her Australian childhood home following her father’s death, plans to transform the house’s contents into an installation in the tradition of Chinese artist Song Dong.

From its first sentence – 114 words long and Proustian – Wall exudes an unrelenting obsessiveness. It is written in the second person as a stream of cyclical ruminations addressed to ‘Teun’, presumably the narrator’s partner. ‘And so’ and ‘which is to say’ are recurring phrases. There are no section breaks or chapter breaks; a part break 118 pages into the novel is the only breath it takes. The typesetting in A format – lines unconventionally long, tight, and small – has a similar effect that, while oppressive, suits the wall of text. In its demands on the reader, this is a book out of step with the attention-economy era, but one whose complexity pays off.

Craig commits to the Sisyphean task of bridging the gap between experience and representation, between life and art. The narrator, like her father, insists almost aggressively on being understood on her terms.

Thwarted communication is at the heart of the work. Amid near-epiphanies, the narrator feels ‘always on the verge of explaining in full’ but is ultimately unable ‘to think or listen or speak’:

… soon it starts to become not the thing I thought I was telling you. Not at all the thing (I thought) I was telling you. Yes, as I would quickly realise, even then as I was speaking – in the very process, the middle, the act of speaking – and even or especially when the thing that was important (to me) to describe – that I had to tell you – when this thing could not be received by you.

This novel of remembrance takes place almost entirely within the narrator’s mind. It is not plot-driven or character-driven, but language-driven. Yet, mysteriously, narrative tension builds. As an editor, I wondered how one would go about editing such a work. I pulled off the shelf Gerald Murnane, Marcel Proust, and John Barth, but found it was not their style I was reminded of but the idiosyncrasy of their rhythm, the consistency of their cadence. Wall is a beast of a novel, a demanding but rewarding work, and a memorable exploration of the tangles of life and art.

Comments powered by CComment