- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fade to black

- Article Subtitle: A dramatist of disillusion

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

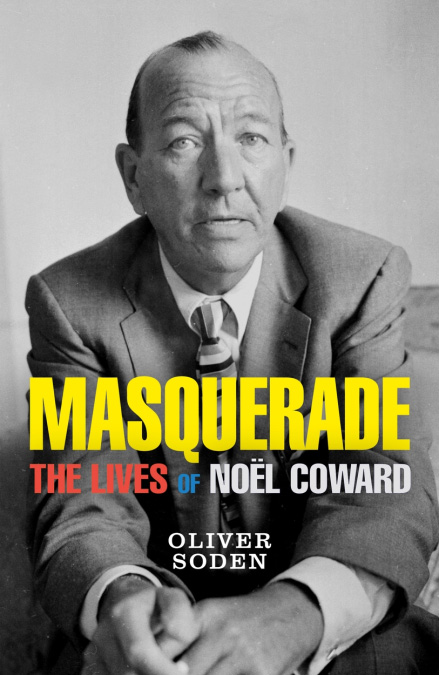

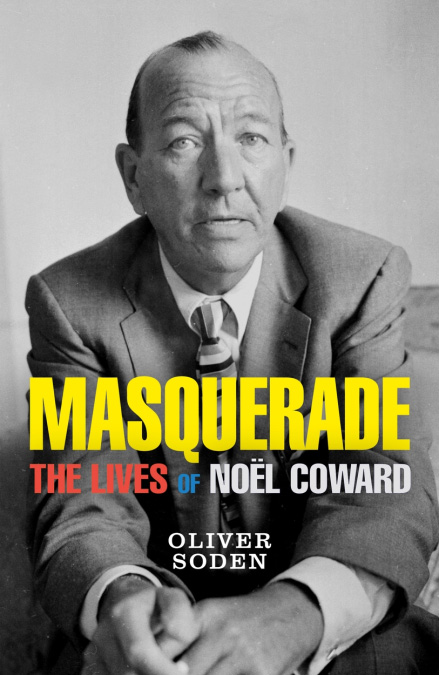

You could hardly ask for a better tour guide through the artistic travails and triumphs of the twentieth century. Born as the previous century was closing its shutters, Noël Coward dominated the London stage in the interwar years, butted heads with the Angry Young Men in the 1950s, before wrenching victory from the jaws of disfavour in his final years in a series of stunning revivals.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Paul Kildea reviews 'Masquerade: The lives of Noël Coward' by Oliver Soden

- Book 1 Title: Masquerade

- Book 1 Subtitle: The lives of Noël Coward

- Book 1 Biblio: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $34.99 pb, 656 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

In the early 1920s, he had been struck by the pace of dialogue in Broadway plays and brought the lesson home with him (‘Wait till I get back to Shaftesbury Avenue!!’). These were the years just before American talkies changed humour forever, the Marx Brothers in their wise-arsery the most obvious gauntlet throwers. It took Coward a few attempts, but in 1924 he had a knockout success with The Vortex, after which, as Oliver Soden observes, his life changed for ever. In three dense acts, Coward set out his stall: homosexuality, drug use, intergenerational love, and the mores of the Bright Young Things, which Evelyn Waugh would soon skewer with such precision. These were themes Coward never really let go, carefully navigating the fissure between public taste and the Lord Chamberlain’s strictures. Even the play’s central figure, the ageing beauty Florence Lancaster, who takes up with a much younger lover, was a mirror to a generation of women who had lost their husbands and much more besides in World War I. Robert Graves would rip off this bandage five years later in his excoriating Good-Bye to All That, yet, as with Waugh, Coward got there first.

It is impossible to overstate Coward’s hold on the English stage and imagination after The Vortex. Only two year later, newspapers would write of the Noël Coward Era, comparing the playwright (appropriately) to Wilde and (improbably) to Shakespeare. One critic of The Vortex landed on a more apposite comparison: ‘It makes Mr Somerset Maugham’s smart set look hopelessly old-fashioned.’ Coward and his producers mined the works and stories he had been churning out since his teen years (the equivalent of Benjamin Britten’s drawer of ‘early horrors’), and his work was soon everywhere, Broadway included. His musical revue On with the Dance (1925), which he wrote while acting in The Vortex, was birthed only after a twenty-six-hour dress rehearsal, such was his sway and the scale of his ambition.

Part Two

Soden’s section on The Vortex illustrates the considerable strengths and strategic weaknesses of this very fine biography. He is great on the play’s gay subtext, as he is throughout the book on changing attitudes towards homosexuality as the century progressed, and indeed Coward’s role in these changes. (The Oxford English Dictionary lists this line from Bitter Sweet as the second attributable use of the word gay meaning homosexual: ‘Haughty boys, naughty boys … we are the reason for the “Nineties” being gay.’) He is similarly good on the politics of the characters and period too, as he is on Coward’s own reactionary views – all Empire and Tories and great gulps of Churchill worship. (He thought Gandhi’s assassination in 1948 ‘a bloody good thing but far too late’.) Yet Soden follows this astute literary criticism and scene-setting with pages of review excerpts, as if compiled by a publicist’s intern over lunch.

To be fair, he gives us due warning, setting out his stall in a Prologue in which he notes that each of the book’s nine sections is ‘loosely structured as one of the varied genres in which he wrote: plays, musicals, revues, screenplays, short stories.’ ‘Does it work?’ I scribbled next to this early paragraph. Well, it does, though the extent to which you are charmed by his technique will depend on how much you like the structure of this review. Of course, you can ignore the frame and focus on the picture, yet there remain downsides to Soden abandoning his unfussy, careful prose. The final chapter, for example – of both the book and Coward’s life – is strangely unmoving; here, Soden collages diary entries, quotes from letters, excerpts from other biographies, interviews, and recollections into a postmodernist ‘Late Play’, the author a stone-hearted playwright refusing us an emotional farewell.

Yet there is so much to admire, so much new material to absorb. (It is gratifying to read the sentences on the tenor Hans Unterfucker whom Coward so desperately wanted to cast in anything, if only for the billing.) In many ways, the alienation and decline Coward experienced in the 1950s is more compelling than his great successes in previous decades, and certainly more interesting than his very long war, at least in this telling. But Coward’s work ethic, his ready wit, and the changing societal values leap from every page.

Upon undertaking the project, Soden wrote to one of Coward’s previous biographers, the luminous Philip Hoare, to seek his blessing, hoping that a new biography twenty-four years after his was not too soon. ‘Dear Oliver,’ Hoare replied. ‘Twenty-four years? Of course it’s time!’ Yes, it is time, and Soden has risen masterfully to the challenge.

Comments powered by CComment