- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

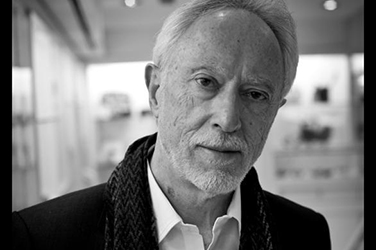

- Custom Article Title: An obscure prodigy

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An obscure prodigy

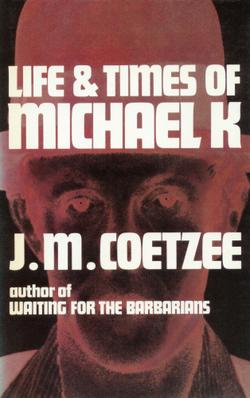

- Article Subtitle: J.M. Coetzee’s 'Life and Times of Michael K' at forty

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Why should I be expected to rise above my times? Is it my doing that my times have been so shameful? Why should it be left to me, old and sick and full of pain, to lift myself out of this pit of disgrace?

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): J.M. Coetzee’s Life and Times of Michael K at forty

Coetzee’s recent Jesus trilogy (2013–19) makes overt a latent feature of this existential angst – namely, that it is culturally if not actually Christian. The moral lexicon of his fiction – the recurring concepts of shame and disgrace, in particular – is at the very least religiously inflected, in that it speaks of an internalisation of a fallen state. It assumes a burden of guilt more onerous than mere personal culpability. The ironic twist Coetzee gives to his characters’ tortuous questioning is that their search for answers is part of their dilemma: it is not possible to think or will your way to a counterposing state of ‘grace’, which is by definition something that can only be mysteriously bestowed.

The movement of Coetzee’s fiction is thus, somewhat paradoxically for such a cerebral writer, towards a renunciation of bootless intellectualising. In the Jesus trilogy, the notional divinity of the precocious child, David, manifests itself in his preternatural idealism, his refusal to be schooled in the constraining laws of earthbound rationality. But Coetzee, for much of his career, has been more inclined to lower his gaze. His work gestures towards a materiality that is prior to language and ideas, glimpsing in this the possibility of an obverse state of grace, often represented by animals, which are apt to appear as embodiments of equanimity. Their positive counterexample is their groundedness, their ability to live within themselves, their refusal to torment themselves with abstractions. As Mrs Curren muses, animals do not compound the indignity of their suffering by trying to find meaning in it.

Coetzee’s fourth book, Life and Times of Michael K (1983), takes on its particular significance in light of this defining conflict. In the context of his long career, it is landmark work. Arriving in the wake of Waiting for the Barbarians – perhaps the greatest of his early novels – it consolidated his international reputation, winning him the Booker Prize for the first time. But it also received some trenchant criticism from no less an eminence than Nadine Gordimer, who suggested that Life and Times of Michael K – a novel steeped in the violence and degradation of the apartheid regime – was avoiding the political realities of the situation by shifting its harrowing narrative into the realm of allegory.

The criticism seems a little odd in hindsight, given how deeply Coetzee’s South African novels are marked by the horrors of apartheid and how explicitly they grapple with the legacies of colonialism. Gordimer’s allegiance to Georg Lukács’s notion that realism is the appropriate genre for the politically engaged novelist now seems dated, even a little quaint. But her criticism hit a nerve, largely because Coetzee does indeed cast Michael K as a strange mythical figure, whose implications are not ‘political’ in any immediate sense. ‘I am not sure he is wholly of our world,’ observes the medical officer who narrates the second section of the novel. Michael is sanctified as an ‘original soul … a human soul above and beneath classification, a soul blessedly untouched by doctrine, untouched by history’. He is the ‘obscurest of the obscure, so obscure as to be a prodigy’.

One way to make sense of these extravagant claims might be to read Life and Times of Michael K as a Rousseauean thought experiment. Michael is an innocent, a kind of holy fool, his nature uncorrupted by society, a condition the novel bestows on him via a combination of ignorance and estrangement. In this, he inverts the familiar Coetzeean perspective. As he navigates his way through a war-ravaged land, he is subjected to a series of trials. The illness and death of his mother at the beginning of the novel severs his only familial bond and exposes him to the symptoms of a broken society: unemployment, civil unrest, an obstructive and opaque bureaucracy, an overwhelmed and dysfunctional hospital system, forced labour, a corrupt military, poverty and vagrancy, an internment camp. These trials sometimes spark his moral conscience (‘Do I believe in helping people, he wondered’) and there are moments when Michael thinks of his ordeal as a ‘lesson’ and an ‘education’. But he gains no real insight into the historical and political forces that have generated his misery, nor does he display any interest in understanding them. For Michael, they are simply how the world is.

This is the conceptual paradox that seems to give teeth to Gordimer’s objection. Michael is enigmatic because he is a concrete depiction of an impossibility. The novel means to test his uncanny innocence against the scourge of reality, yet that innocence is predicated on his status as a simpleton who is alienated from his times, making his political inconsequence something of a fait accompli. The oddness of his character exists in an uneasy relation with the stylised world of the novel, which is at once specific (it is explicitly set in South Africa) and indistinct (the historical context is left vague). The medical officer apostrophises to Michael that there is something significant in ‘the originality of the resistance you offered. You were not a hero and you did not appear to be.’ But the unpalatable form of that unheroic ‘resistance’ is to remain helpless in the face of misery and oppression. Even when Michael tries to establish his independence, attempting to grow pumpkins on an abandoned farm, the Crusoean fantasy of enterprising self-sufficiency ends in failure. His fate is to be caught up again in the war he does not comprehend, dragged back into history against his will. The final section of the novel completes his descent into abjection when he finally succumbs to the corrupting influence of society and takes to drink. With remorseless novelistic logic, Michael’s life is undone by his times. No one can remain untouched by history and doctrine. The idea is absurd.

In this sense, Life and Times of Michael K is rigorous enough to dismantle its own premises, undermine the conceit that Michael is some kind of supra-historical, quasi-religious figure. His passive ‘resistance’, his ‘presentiment of a single meaning’, and the portentous biblical authority of his declaration ‘I am what I am’ are ultimately harbingers of nothing, or at least nothing of any consequence. The obscure nature of his purported specialness also brings in train a number of retrograde implications – sanctification of pointless suffering, idealisation of simple-mindedness, conflation of virtue and victimhood – which the novel seeks to address via a structural ingenuity. The medical officer’s confession serves a metafictional purpose: it is also the novel’s confession, the point at which its implications and intentions are laid bare. He lavishes his inscrutable patient with significance, describing their brief encounter in revelatory terms in a way that spills over into self-consciousness. Michael’s attributed meaning becomes so exaggerated, so overdetermined, that it reveals itself to be a projection.

Therein resides the crucial ambiguity. The novel ironises the attribution of profundity, but it does not want to disavow that profundity. If a work of fiction can be said to express a desire, it would certainly appear to be the case that, on some level, Life and Times of Michael K wants a trace of revelatory possibility to cling to its emaciated protagonist. It wants us to recognise the pathos and the battered dignity of Michael’s late realisation that there is ‘nothing to be ashamed of in being simple’. It wants to be able to examine a life like Michael’s – a life marred by undeserved misfortunes and cruelties, one stripped back to the most basic imperatives of survival – and find something other than meaningless suffering.

In this, Life and Times of Michael K asks a timeless question that has motivated much of Coetzee’s work: what is the ontological status of moral ideas when the world around us seems to deny them? In what sense, if any, might they be said to inhere in reality? Christian mythology gives us, in the life and death of Jesus, an allegory about the unhappy fate of goodness in a corrupt world. The malformed figure of Michael K is an attempt to bring that myth and the impossible transhistorical hope it represents into contact with history; his story is an attempt to find a literary form that might allow such an idea to be adequately expressed. Part of the unsettling power of Life and Times of Michael K is that this conceptual difficulty is not resolved. It would be another thirty years before Coetzee would undertake to address the same mythical inheritance, creating in the character of David a figure who might yet bear the impossible weight of signification. But it is no small matter that the extraordinary Jesus trilogy is not set in any recognisable reality, but in an imaginatively liberated realm of absolute fiction.

This article is one of a series of ABR commentaries on cultural and political subjects being funded by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.

Comments powered by CComment