- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Alloys to happiness

- Article Subtitle: The last Frank Bascombe novel

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When pushed to vote on the bleakest poem among Philip Larkin’s death-obsessed body of work, most would likely stump for his late masterpiece ‘Aubade’, that arid interrogation of human finitude. Yet his ‘The Building’, from 1972, is in many ways a more savage appraisal of individual extinction and the structures we build in an attempt to deny it: ‘Higher than the handsomest hotel / The lucent comb shows up for miles …’ Larkin was referring here to the Hull Royal Infirmary, a modernist pile which loomed over the poet’s hometown after it opened in 1967. Yet the poem could just as easily be translocated to Rochester, Minnesota, where the substantial modern tower of the Mayo Clinic stands: a building around which, too, surrounding streets stand like ‘a great sigh out of the last century’.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

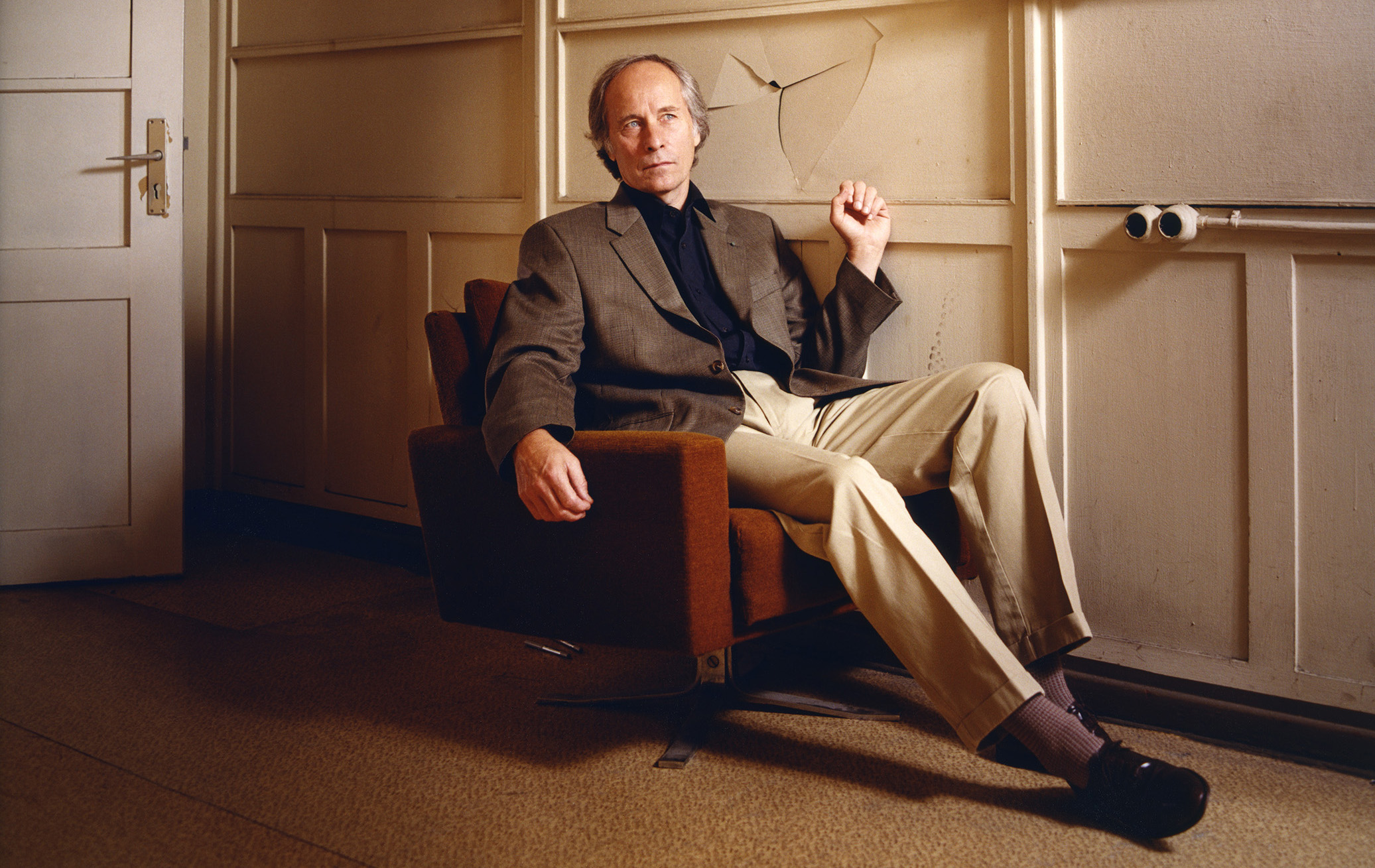

- Article Hero Image Caption: Richard Ford, 2002 (Oliver Mark via Wikimedia Commons)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Geordie Williamson reviews 'Be Mine' by Richard Ford

- Book 1 Title: Be Mine

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $32.99 pb, 352 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

We meet the pair during the concluding days of their stay in the city of Rochester. The trials which Paul has undertaken are not designed to save his life, or even to extend it. The forty-seven year old, whose existence has never taken the shape he might have wished, wants his death to provide some modest future hope for others.

Mostly, though, we see Paul – eccentric in manner, often wheelchair-bound, tending to corpulence – through the imperfectly loving and sometimes troubled eyes of his father. Frank has lost none of the humour and loquacity that made earlier Bascombe novels such a pleasure to linger in. He still sees changing America through lenses at once poetic and sociological, finding delight in strip malls and highway Hiltons, the low mimetic of American modernity built over the most sublimely vast and changeable of landscapes.

Minnesota in full winter is no exception. Frank and Paul have rented a sprawling bungalow in Rochester, where the older man, a New Jerseyan, has ample time to muse on finding himself in this unlikely spot.

Yes, this is a space adequate for doing whatever we think we’re doing. There is a small river. That direction we face is west. The Twin Cities are that way (out of sight, but unmissable). There, are major arteries. There, the first tier suburbs, the second and third. That colossus of glass and steel in the middle ground … that is the Clinic where everything happening is of the utmost import. And that space of leafless maples, elms and oaks just beyond, is where our house sits, barely visible beside a large blue spruce. And beyond all that is prairie. Expanding and expanding.

What Frank is trying to do is to take the great American randomness and arrange it into some explicable order. At ‘some point it is good,’ he concludes, ‘possibly necessary, to set your own coordinates.’

The second half of the novel, which describes a road trip undertaken by the pair, driving a vintage RV to visit that ‘most notional’ of American sights, Mount Rushmore, is an effort to bring interior and exterior coordinates into alignment. Paul is declining with a swiftness unanticipated by his father, discarding significant functions like someone stripping off for a swim.

Time, then, is forcing upon both an accelerated reckoning. Only the smallest and swiftest of pleasures may be wrestled from the time they have remaining. A visit to the gift shop of the Mitchell Corn Palace in South Dakota, say, or brief and phatic communion with a nurse or hotel manageress. Or the endless badinage between father and son, elicited from the vacuum of hours on the road, which occasionally veers from family jokes to the great imponderables. Mount Rushmore, when it is finally approached, disappoints: it is ‘monumental without being majestic’, Paul observes.

If Be Mine lacks some of the easy grace of the preceding Bascombe novels – Paul is often truculent in his pain, Frank more tart and judgemental concerning the Trumpian squalor afflicting his nation in late 2020 – its final effects are stronger.

Bascombe recalls reading Anthony Trollope’s Autobiography, in which the English author notes ‘that there exists in life a sorrow so great that sorrow becomes an alloy to happiness’. Be Mine is a tougher book because this is an alloy Frank Bascombe has come to know.

The final pages of the novel, which jump forward to describe Paul’s death and its aftermath, is a gleaming instance of this new bond. Frank’s orientation towards death has grown balanced and supple, and he suggests that some art and thought directed towards these matters makes facing them harder than it needs to be.

Frank is referring to Heidegger here, having read the German philosopher in a desultory way throughout the narrative of Be Mine, though he could just as easily be talking about Larkin. That poet, at the conclusion of ‘The Building’, mounts his bitterest condemnation of our situation:

… All know they are going to die.

Not yet, perhaps not here, but in the end,

And somewhere like this. That is what it means,

This clean-sliced cliff; a struggle to transcend

The thought of dying, for unless its powers

Outbuild cathedrals nothing contravenes

The coming dark, though crowds each evening try

With wasteful, weak, propitiatory flowers.

Frank Bascombe would readily admit the absolute fact of death Larkin lays down. But he would not regard those ‘propitiatory flowers’ as wasteful or weak. That final, effortful road trip with Paul was a gesture of love, and its memory a balm, of sorts, to an old man who has outlived his son.

Comments powered by CComment