- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The master welder

- Article Subtitle: Fragments of autobiography from Robert Lowell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At his death in 1977, Robert Lowell was considered one of the greatest and most influential American poets of the century. He had absorbed the academic formalism of the Fugitives and New Critics, but had gone beyond it with a humanising anger, the suffering visions of a manic-depressive. Among the Confessional Poets – as W.D. Snodgrass, Anne Sexton, Sylvia Plath and others had come to be called – he was loftier, more prodigious and prolific. Seamus Heaney, who outgrew Lowell’s influence to become a figure of global importance, called him our ‘master elegist / and welder of English’. Not wielder, but welder. Lowell forged his poems, putting words together like pieces of steel. Another critic called his early style ‘imbricated’ for its packed masonry of sound.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Mason reviews 'Memoirs' by Robert Lowell, edited by Steven Gould Axelrod and Grzegorz Kosc

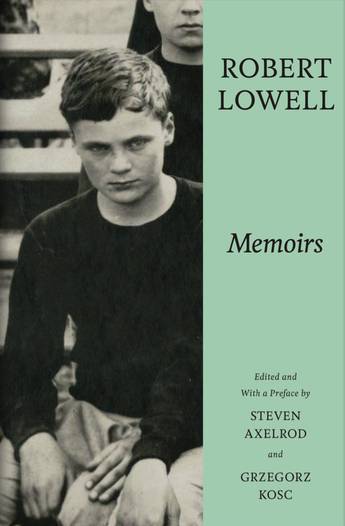

- Book 1 Title: Memoirs

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $79.99 hb, 397 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Unlike his friend Randall Jarrell, Lowell was not a great critic. A volume of his Collected Prose, edited by Robert Giroux, was published in 1987 but did little to burnish the poet’s reputation. Already it was clear that his prose existed partly to furnish anecdotes and phrases for his poems. His most famous memoir, ‘91 Revere Street’, appeared first in his breakthrough collection of poetry, Life Studies (1959). It recalled an unhappy childhood in Boston – his disappointed mother, ineffectual father, and the more vivid relatives who surrounded them, particularly his maternal grandfather, Arthur Winslow. With this new book, Memoirs, which gathers additional prose that has languished for decades among Lowell’s papers, we can put ‘91 Revere Street’ in perspective. After his first debilitating manic episode in 1954, which resulted in hospitalisation, electroshock treatments, and psychotherapy, Lowell began writing his autobiography. He worked at it seriously for about two years, then set it aside to compose poems from the same material.

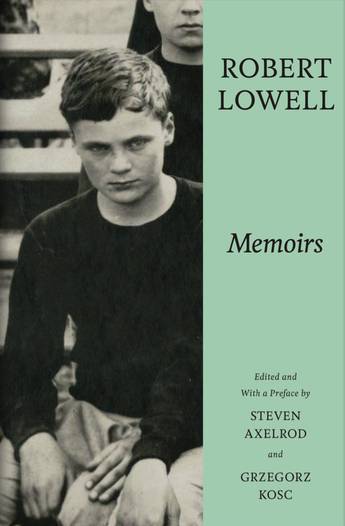

The twenty existing chapters on childhood and family life, some of them fragmentary and unfinished, allow us to see Lowell’s particular way of blending family lore (his relations included poets James Russell Lowell and Amy Lowell) with the larger history of his country, or at least the Protestant, Eastern Seaboard part of it. His immediate family was not rich but nevertheless felt entitled, and a certain patrician entitlement remained with Lowell for the rest of his days. He would win his first Pulitzer at thirty and become Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (now called Poet Laureate), and he would go on to win every honour an American poet could wish for, short of the Nobel Prize. But the photo of Lowell on the jacket of Memoirs shows him as a bitter, rebellious schoolboy. As a young man, he defied his family’s wishes, left Harvard to camp out in the yard of a poet he admired, Allen Tate, then went to study with John Crowe Ransom at Kenyon College. This is the same young man who converted to Catholicism and spent a year in jail as a conscientious objector during World War II. He was a rebel who could never forget the genteel snobbery of his family. As he writes of his grandfather Winslow, ‘Looking about, he took satisfaction in seeing himself surrounded by neighbors whose reputations had made state, if not universal, history.’

While there are dazzling sentences in the childhood memoirs, and passages of superb description, the book never gels. The second section of memoirs, detailing his episodes of ‘pathological enthusiasm’ and hospitalisation, is far more harrowing and surreal: ‘No one understood my humor. I grew red and confused. The air in the room began to tighten around me.’ The material here feels fresher, wilder, yet little of that wildness got into his poems, which too seldom escape their origins in prose.

Some of his memoirs of other writers, taking up the third section of this book, have appeared in earlier volumes, but here one finds more of them, and finds Lowell at his best: warm, funny, affectionate. He has beautiful things to say about Tate, Ransom, Ford Madox Ford, Robert Frost, and even Ezra Pound. The notes inform us that he began his memoir of T.S. Eliot by admitting that he cried at the news of Eliot’s death. A key memoir of William Carlos Williams elucidates the ‘poetry wars’ of the 1950s between camps of poets Lowell referred to as the ‘cooked’ versus the ‘raw’. Memoirs of John Berryman and Randall Jarrell wonder why these two brilliant men never liked each other, but no one has written more tenderly about their abbreviated lives. Berryman jumped to his death from a bridge in Minneapolis; Jarrell strayed onto a highway near a North Carolina hospital where he had been treated for depression, and was hit by a car. Lowell observes, ‘Jarrell’s death was the sadder. If it hadn’t happened, it wouldn’t have happened. He would be with me now, in full power, as far as one may at fifty.’ Lowell, of course, died of a heart attack in a taxi, aged sixty, still hoping to repair his fragmented life.

Comments powered by CComment