- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Two new actors' memoirs

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Veiled performances

- Article Subtitle: Two evasive memoirs

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Despite their proliferation, celebrity memoirs often seem incapable of justifying their own existence: a string of carefully curated anecdotes woven together to approximate a life already lived in the glare of the media. Perhaps because actors are on the one hand concealed by the roles they play, and on the other exposed to the prying eyes of the public, their autobiographies tend to inhabit a paradoxical netherworld of disclosure and obfuscation, cautious oscillations on a back off/come hither axis. Both Sam Neill’s and Heather Mitchell’s recent memoirs traverse this uneasy ground, feeding us sometimes incredibly intimate details while remaining stubbornly mute on the larger questions of their careers.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tim Byrne reviews 'Did I Ever Tell You This? A memoir' by Sam Neill and 'Everything and Nothing: A memoir' by Heather Mitchell

- Book 1 Title: Did I Ever Tell You This?

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $49.99 hb, 398 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

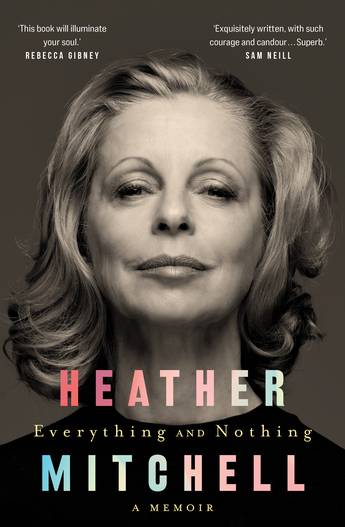

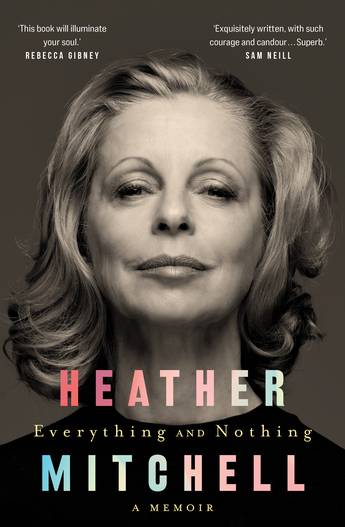

- Book 2 Title: Everything and Nothing

- Book 2 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 2 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $34.99 pb, 295 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Sibling relationships had slightly more impact on Neill’s formative development, but it was really the friendships he made outside the family structure that stuck with him. Bill Nutt – another Nigel who changed his name – was one of the first, ‘the most naturally gifted comic actor I’ve ever worked with (with the possible exception of Robin Williams, but it’s bloody close)’. He was tragically impaired by a car accident after leaving school. Bryan Brown features heavily, the kind of friend who substitutes goading and pranksterism for overt signs of affection, but is also clearly intensely devoted. There is a jocularity about these depictions, a boys-own-adventure mood that is charming or wearisome depending on your predisposition. Certainly, Neill is generous and sincere, although as the work progresses, his disinclination or maybe inability to prosecute or analyse his relationships begins to seem less a case of modesty and more a character flaw. At one point, he says he’s ‘as shallow as a puddle’, and it becomes increasingly difficult to disagree with him.

There are occasional flashes of insight and some juicy behind-the-scenes confessions, just enough to keep the reader engaged. We hear of John Gielgud’s tendency to drop faux pas like bits of tissue; Harvey Keitel’s meanness and obduracy during the filming of The Piano (1993); and Neill’s fractious, and ultimately chilly, relationship with Judy Davis. And yet, overall, Neill seems a reluctant celebrity raconteur – too deferential, too nice. He is happier talking about his pigs and his vineyards, the state of New Zealand architecture and the pleasures of New Zealand art. It is a discursive, pockmarked journey through a life, rendered unremarkable despite Neill’s proximity to fame and fortune.

Heather Mitchell’s Everything and Nothing is a far more considered, penetrative work; her prose is as poised and deliberate as her many stage roles, and her willingness to plumb emotional depths is courageous and bracing. Her opening chapter tells of the death of her mother from cancer when Mitchell was a teenager. In the space of a few deft pages, she manages to fold in complex questions of sexual awakening, mortality, and the ethical responsibilities of a dying parent. There is real skill here, an ability to conjure whole worlds with judicious word choice and germane detail. When her mother is being taken away in an ambulance, the last time Mitchell would see her alive, ‘[t]here was no siren, only the sound of Joan, our neighbour, sobbing near the gate. I wondered why she was there, what she knew and what gave her the right to cry.’ The weight of that ‘right’, its bitterness and incomprehension, is marvellously apt and evocative.

Motherhood – and its concomitant sensations of guilt and responsibility – is a key theme in the memoir, sharpened by Mitchell’s own diagnosis of breast cancer when her two sons were young. That crisis echoes her own confusion at losing a mother she didn’t realise was sick, and raises questions around the ethics of illness; how much should children be expected to bear, and when does the understandable desire to protect and shelter become damaging in itself? Mitchell approaches the subject with an enquiring candour, a willingness to accommodate doubt and ambivalence.

She is equally circumspect on the issue of gendered violence, particularly in a chapter entitled ‘Are You Decent?’, which chronicles various incidents of sexual assault – from a dentist to a stranger on a train – along with Mitchell’s dawning sense of injustice at having her body invaded by men throughout her life and career. While she treads cautiously through this minefield, sidestepping recent high-profile allegations on Australian stages, she does build a strong picture of women who came of age in the 1970s, desperate to unshackle themselves from the strictures of their parents’ generation but blindly walking into dangerous sexual territories of their own.

What is almost completely missing, even more than in Neill’s book, is a comprehensive portrait of life as a professional actor. Most stage anecdotes revolve around the difficulties Mitchell has had juggling her personal and professional lives, the intersection of career and motherhood. While some of these are astonishing – one involving the surreptitious insertion of a tampon in front of a live audience will stay with me a long time – they often feel subsidiary, as if Mitchell were only incidentally an actor. It is almost perverse: as if a renowned surgeon were to write a memoir that never mentioned a hospital.

Neill’s Did I Ever Tell You This? and Mitchell’s Everything and Nothing share similarities, notably ongoing struggles with cancer and a reluctance to dish the dirt on colleagues past and present. But what really links them is their insistent humility, which seems noble but also veils something: a pathological fear of being thought prideful or pretentious perhaps. Antony Sher may have presented himself as an artistic giant in his diary of an actor’s process, Year of the King (1985), but at least he gave the reader extraordinary access to life on stage and off. Neill and Mitchell prefer us to remain perennial audience members, forever in the dark.

Comments powered by CComment