- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: ONE MAN CONTROL

- Article Subtitle: An enthralling study of the young Rupert Murdoch

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

There is every reason for wanting to get to the bottom of Rupert Murdoch. It is arguable that he has done more than any modern individual to shape public life, policy, and conversation in those parts of the Anglosphere where his media interests either dominate or hold serious sway. His influence is richly textured, transformative. Beyond bringing a populist insouciance to his host of print and television properties, he is also unafraid of using his reach as a political weapon, a tactic used with such vehement ubiquity that governments pre-emptively buckle to what they suppose is the Murdoch line. Debate is thus distorted and circumscribed. Public anxiety is co-opted as a cynically exploited tool of sales and marketing.

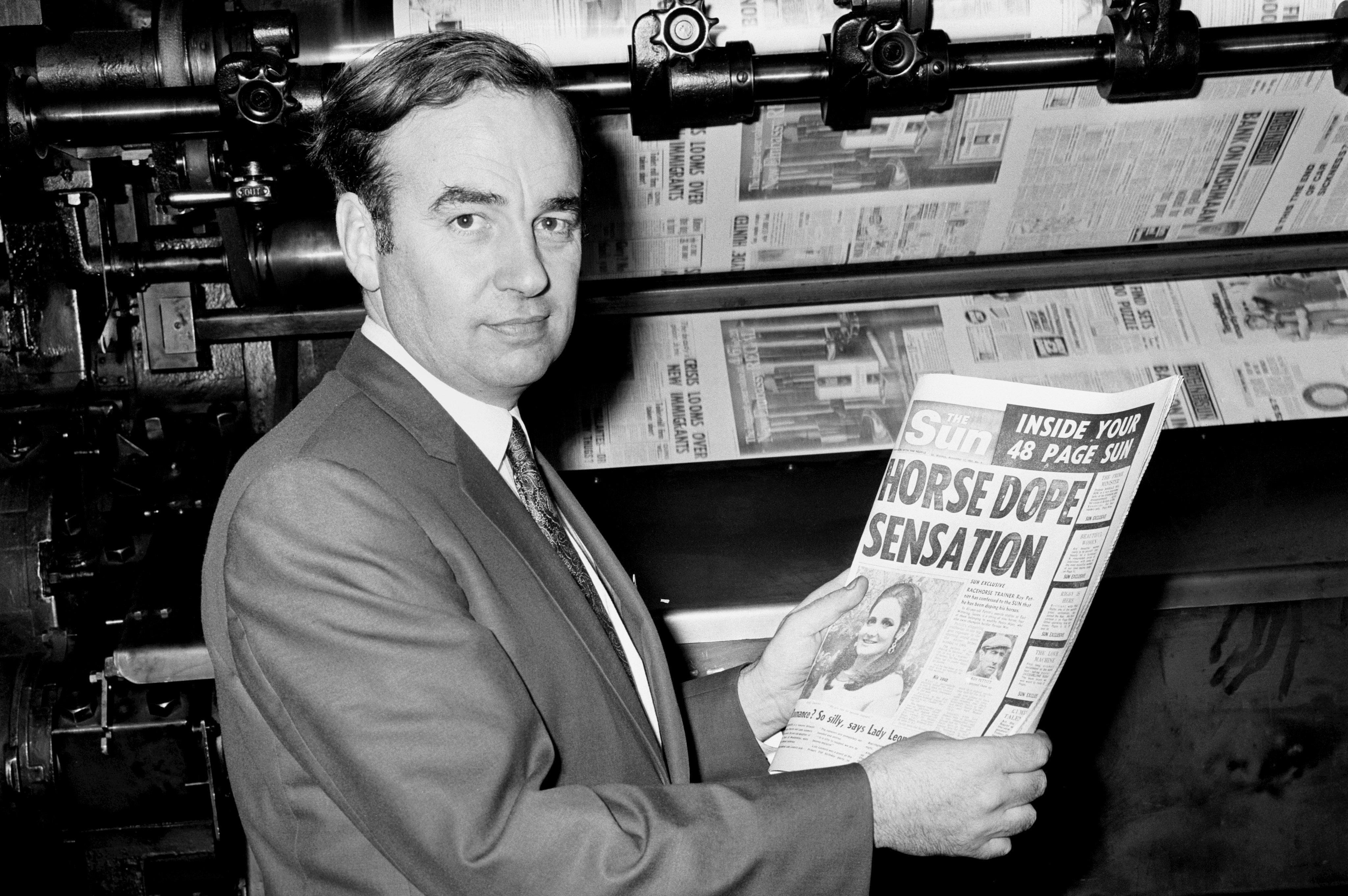

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: Rupert Murdoch at the News of the World building in London, 1969 (PA Images/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jonathan Green reviews 'Young Rupert: The making of the Murdoch empire' by Walter Marsh

- Book 1 Title: Young Rupert

- Book 1 Subtitle: The making of the Murdoch empire

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $35 pb, 344 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

We begin with inheritance, for the rise and rise of Keith Rupert Murdoch was the specific and stated design of Keith Arthur Murdoch (1885–1952), his father. There was no intricate play of succession here: the only son would have it all. Sir Keith made his hopes clear in his will: ‘I desire that my said son Keith Rupert Murdoch should have the great opportunity of spending a useful and altruistic life in newspaper and broadcasting activities.’

Amassing a potent legacy gave a frame to Sir Keith’s working life of steady media acquisition. ‘I cannot afford to die,’ Sir Keith had told a family friend, ‘I’ve got to see my son established, not leave him like a lamb to be destroyed by these people.’

Marsh’s deep study is bedded in detailed and meticulous research rendered unfailingly lively and enthralling in the telling. In span it takes us from before Rupert’s birth in 1931 to his victory over the British print unions at Wapping in 1986. The narrative is front-loaded to the early twentieth century, giving a vivid account of a formative time in Australian media, when powerful men jockeyed for domination.

They are not without blemish. Sir Keith, self-made journalist hero of the famous, if somewhat fanciful, Gallipoli dispatch – ‘a stirring but flawed polemic’, writes Marsh – also seems to have been something of an anti-Semite. His rise – first as managing director, then as chairman of Melbourne’s Herald and Weekly Times Ltd – was, he notes, ‘one time when the Jews met their master’, though he would later struggle to keep that newspaper from the hands of ‘salvaging Jews’. He was a man of physical presence and charisma, the type who inspired loyal, almost besotted commitment. His mentor was the British tabloid baron Lord Northcliffe. A relationship of considerable mutual admiration, it was a formative one for Sir Keith, who was dubbed ‘Lord Southcliffe’ by local wags.

One piece of advice from Northcliffe was telling: an inspiration to Sir Keith, and perhaps also to his son. They are certainly words Rupert would eventually live by. The key to success in the newspaper business was absolute personal power, or as Northcliffe put it in a telegram from December 1921:

FACT YOU HAVE COMPLETE CONTROL / ONE MAN CONTROL / ESSENTIAL / NEWSPAPER BUSINESS / CHIEF

Young Rupert was raised in a climate of ‘loving discipline’ and it was presumably a combination of the two that, on a sea voyage to England, sees his mother, Elisabeth, teach him to swim by throwing him into the ship’s pool and refusing ‘to let anyone help the blond-haired little boy flailing and screaming in the deep end’. A rebellious wilfulness grew in the boy. At Geelong Grammar, he was a ‘polarising figure’, Marsh writes, ‘a loud, if not entirely convincing radical, whose left-wing politics, and rough shambolic manner invited mockery’. He had earned the nickname ‘Comrade Murdoch’.

Still a schoolboy, he would form a relationship with a man who would become his father’s trusted lieutenant and eventually Rupert’s partner in a formative crisis that blended newspapers, South Australian politics and the law, a moment that becomes a central pillar of this book. That man is journalist and editor Rohan Rivett (1917–77), and Marsh has written his story in almost as much detail as Rupert Murdoch’s.

In consequence, there are times when Murdoch is relegated to what is almost a supporting role, lost in the sweep of this detailed history. But that’s both the truth of his early years and the bedding for a moment when the ruthless Murdoch of later life emerges, in an episode of blunt uncaring that announces the arrival of the fully-formed man.

When Rupert goes to Oxford, Rivett and family follow him as a support troop, sending back dispatches to his sometimes anxious father. The relationship is a little reminiscent of elder brother Brideshead’s brotherly concern for Sebastian Flyte, though Murdoch’s transgressions pale in both scope and severity. The young Murdoch sticks with his socialism, has a bust of Lenin in his rooms, and even attends a British Labour Party conference.

The Rivett relationship also sticks. After his father’s death in 1952, the Adelaide afternoon paper The News is Rupert’s inheritance and the stake on which he will build an empire. Rohan Rivett becomes his editor in chief, and between them they publish a paper of occasionally provocative social conscience, a constant irritant to its staid morning rival, The Advertiser.

It all unravels in 1960 over coverage of the Stuart Royal Commission, an inquiry into the apparently wrongful conviction of Arrernte man Rupert Max Stuart over the murder of a young girl. The News, Rivett, and ‘boy publisher’ Murdoch had campaigned hard while Stuart faced the gallows, sparking the inquiry that would almost be their undoing.

The story is complicated, and takes a goodly chunk of this book to explain, but eventually the Murdoch challenge to the conservative government of Thomas Playford is met with charges of libel, including one of seditious libel, charges that are levelled, contested, and one by one dropped.

Within weeks of this moment of triumph, Rupert Murdoch has sacked Rivett, a friend of almost lifelong standing and a man who has stood by him through thick and very thin. He sacked him by letter, a technique reprised only recently to end his marriage to Jerry Hall. He would sell The News, too, newly entranced by television and Sydney tabloids.

Rupert Murdoch was thus on his way and suddenly recognisably himself. Rivett was left to lament the passing of his share of the dog.

Correction: In an earlier version of this review Jonathan Green sent Rupert Murdoch to the wrong university. Murdoch in fact studied at Oxford. We apologise to everyone at the University of Cambridge.

Comments powered by CComment