- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Law

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: 'Just one murder'

- Article Subtitle: Nick McKenzie’s bracing reportage

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

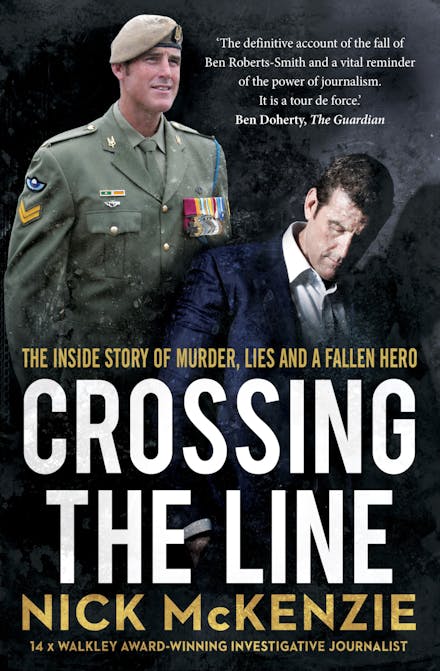

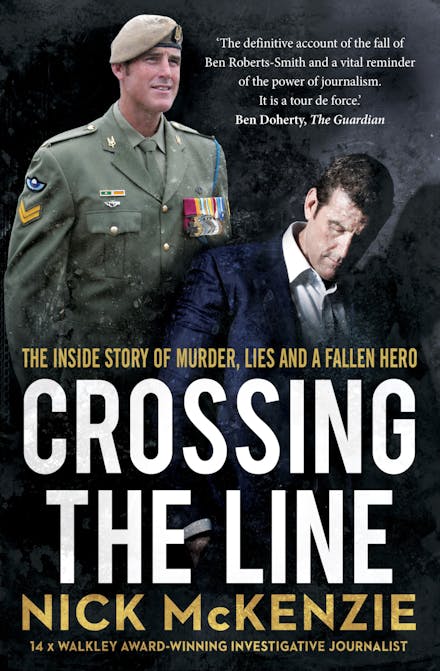

When Justice Anthony Besanko released his judgment on the Ben Roberts-Smith versus Fairfax defamation case on 1 June, there was a lot more riding on his decision than the reputation of the principal parties and who would be landed with the eye-watering legal bills. Had the verdict gone against Fairfax, its reporters, Nick McKenzie, Chris Masters, and, to a lesser extent, Dan Oakes, would have struggled to return to or resurrect their careers. Defeat would have had a chilling effect on genuinely probing investigative reporting. In the face of such a decision, media organisations and editors around the country would have thought long and hard about letting their journalists pursue well-connected and well-resourced public figures, let alone defend their findings in court. But there was more at stake than that. The ‘defamation trial of the century’ was also widely, if inaccurately, regarded as a war crimes trial by proxy. While Roberts-Smith was not on trial for any of the crimes McKenzie and Masters alleged that he had committed or facilitated, had Justice Besanko found that the reporters had defamed him it would have made the pursuit of war crimes charges against Roberts-Smith more unlikely, or more difficult. The sense of relief at Besanko’s judgment was near universal. It not only emboldened the nation’s investigative reporters and their editors but also opened the way for the full and free pursuit of those members of Australia’s Special Forces credibly identified by the Brereton Report (2020) as having committed war crimes in Afghanistan.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Kevin Foster reviews 'Crossing the Line' by Nick McKenzie

- Book 1 Title: Crossing the Line

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $34.99 pb, 475 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Justice Besanko’s courtroom was the cockpit not only for detailed disputation about what Roberts-Smith did and did not do in Afghanistan and Australia. These arguments were also, in part, proxy for long-held, passionately contested myths about the Australian military and the public’s attitudes towards them, as refracted through the media. Hence, Besanko’s judgment also impinged on core matters of national self-image. Since receiving his Victoria Cross in 2011, Roberts-Smith had emerged as both ‘the poster-boy of the nation’s modern military’ and the living link to Anzac. One of his principal champions, former defence minister, Liberal Party leader, and, at the time, director of the Australian War Memorial, Dr Brendan Nelson, was especially smitten. Swooning over the ‘most respected, admired and revered Australian soldier in more than half a century’, Nelson accused sections of the Australian media of running a campaign against the nation’s Special Forces, wondering what the nation stood to gain by tearing down its heroes. Not that the media ever got to see much of its heroes on the battlefield in Afghanistan. The fourth estate’s perennial quest for better access, freer movement, and greater liberty to report what it saw there had earned it little more than the enmity of the men and women in uniform, who came to regard reporters as inveterately hostile. As former Chief of Army Peter Leahy noted: ‘The military frequently questions the objectivity and impartiality of many journalists and sets them into camps – only bad stories, mostly bad stories and a precious few worth talking to.’ Had Besanko ruled in Roberts-Smith’s favour, the military and its champions would have pointed to irrefutable proof of the media’s default posture of hostility towards the nation’s armed forces, strengthening the hand of those in Defence and the ADF determined to keep the media off future battlefields and the public in the dark.

McKenzie’s prompt book, Crossing the Line, offers little in the way of startling new facts, though Channel Nine’s eleventh-hour offer to settle proceedings (Nine merged with Fairfax in 2018) was a surprise. It plays principally to the reader’s emotions, successfully evoking what it felt like to build, board, and ride the emotional rollercoaster of the trial. McKenzie’s depiction of the court proceedings and its protagonists is the stuff of pure melodrama as the audience is invited to cheer, boo, and hiss as the opposing legal teams take to the stage. The media’s lawyers are young, brilliant, and, in the case of the original lead counsel, Sandy Dawson, doomed: Dawson withdrew from the case in its early stages when he was diagnosed with a brain tumour that later claimed his life. Largely untested in a case of this magnitude, the lawyers’ caution bespeaks both humility and a painful consciousness of the challenge ahead of them. Their lead counsel, Nic Owens SC, embodies their collective virtues – polite, measured, even a little deferential. His sometimes inconsequential-seeming questions weave a web that neither Roberts-Smith nor his lawyers are aware of until it closes and snares them. In the opposite corner, Roberts-Smith’s legal team are presented as a pair of Victorian villains. Lead counsel, the bombastic Bruce McClintock SC, carries himself ‘like an ageing heavyweight fighter’, full of swagger and aggression. Scoffing at hapless witnesses, jeering at the juniors across the aisle, he also does a strong line in sucking up to the judge. His sidekick, Arthur Moses SC, is more of a sneaking Peter Lorre-style villain. ‘Sneering and supercilious’, barely able to conceal his contempt for the opposing counsel and their witnesses, he fights to rein in his natural tendency towards shrillness and hectoring. Fittingly, as players in a melodrama, both are renowned for their ‘courtroom theatrics’, their mugging and miming, the instant shift from solicitude to stiletto, as they ham-act their way, they feel sure, to a historic settlement in favour of their client and the plaudits of their colleagues in chambers and the public at large.

McKenzie is both a player in the drama and a nervous spectator. Highly strung and a poor sleeper, he exercises obsessively to manage his stress, badgers his legal team, catastrophises, and is persistently psyched out by the easy confidence that Roberts-Smith and his lawyers exude. McKenzie is so easily spooked because he, more than anybody, is conscious of the impediments to a successful outcome in the case. He has to convince at least one eyewitness to stand up in court and testify that in April 2009, at a compound near Kakarak, code-named Whiskey 108, they saw Roberts-Smith shoot a prisoner with a prosthetic leg before he ordered another member of his troop to shoot a second, manacled detainee; or that in September 2012, at the hamlet of Darwan, they saw him kick a handcuffed Afghan farmer, Ali Jan, off a cliff before ordering other soldiers to drag him a few yards away and execute him. ‘One murder. Just one murder’, McKenzie chants to himself – less a plea than a mantra. Only this will get the media’s case over the line and prove the truth of their reporting.

The obstacles to securing this testimony are immense. Most notably, Person 4, who witnessed the shooting at Whiskey 108 and the execution of Ali Jan, was also the soldier ordered by Roberts-Smith to shoot the second man at Whiskey 108. He can-not bear witness to Roberts-Smith’s crime without confessing to his own. Hence, he and his solicitor ignore all approaches from the media’s legal team. Other potential witnesses from the SAS are no more responsive to McKenzie’s approaches. They must first face down a campaign of threats and intimidation, orchestrated by Roberts-Smith, before determining how their commitment to the truth measures up against the profound bonds of loyalty fostered by service in the Regiment. McKenzie and his legal team subpoena their witnesses, agonise over whether they will appear in court, and then sweat over their evidence.

While the media’s legal team methodically assembles its case, and first one then another witness comes forward to corroborate McKenzie’s and Masters’ claims, the shallowness of Roberts-Smith’s legal position is suddenly laid bare. Confronted by a growing line of witnesses to the fact that, as McKenzie and Masters alleged, Roberts-Smith is a murderer, a bully, and a liar, McClintock and Moses are left to do little more than question the witnesses’ motives and impugn their honesty, insisting again and again that their testimony is false, and their falsehood motivated by jealousy and resentment. It is an argument that gains little traction. When it comes to the treatment of Afghan witnesses, McClintock’s performance is revealingly emblematic of the attitudes that enabled the concealment of the SAS’s crimes for so long. Hanifa, Ali Jan’s nephew, who was with him in the hours before Roberts-Smith assaulted and had him murdered, testifies that his uncle’s assailant was an unusually large man in a wet, sandy uniform. Roberts-Smith had waded across the Helmand River after shooting and killing an alleged enemy spotter before interrogating Ali Jan and was the only SAS man in a wet uniform. McClintock rejects Hanifa’s evidence, accusing him of lying in hope of a compensation payment. ’Twas ever thus. Over the years of the ADF deployment in Afghanistan, countless villagers came forward alleging that Australian forces had brutalised them, destroyed their property, killed their livestock, relatives, or community members. The ADF’s ‘rigorous investigation’ of these claims, which we now know to have been a pantomime of accountability, invariably rejected them. The accusers were dismissed as liars, chancing their arm in hope of a fat pay-out. Hanifa concluded his testimony with a dignified refutation of this insistently racist assumption, telling McClintock: ‘Look, brother, I am a witness, I am not afraid of anybody, even if I die I will tell the truth. This is the Pashto customs. It is the tradition. And this is the law. If you witness something like a crime, you have to testify about it.’ Amen to that, brother.

The narrative reaches its climax when, in a moment of high drama, Person 4 unexpectedly takes the stand, dealing Roberts-Smith’s case a mortal blow. For all the larger issues at stake here – freedom of the press, war crimes, the nation’s quixotic addiction to a hollow myth of military exceptionalism – it is greatly to McKenzie’s credit that he never loses sight of the real victims of Australia’s war in Afghanistan. We know nothing about the disabled victim at Whiskey 108 whose souvenired prosthetic leg became the drinking horn of choice in the SAS’s alcoholic Valhalla: the Fat Lady’s Arms. His humiliation remains anonymous. But we do know about Ali Jan. He was a poor subsistence farmer with a wife, Bibi Dhorko, and six children. They lived three hours walk from Darwan where Ali tended a small plot of land, bartered some of what he grew, and struggled to make ends meet. He was a peaceful man who took little interest in politics and regarded armed men with suspicion. On 11 September 2012 he had ridden his donkey to Darwan to collect a few basic supplies for the family – flour, firewood, and a pair of shoes for his daughter. He told his wife he would be home for dinner. She never saw him again. When a relative returned his donkey to the family a few days later, the shoes were still strapped to the animal’s side. Some months after his killing, Bibi gave birth to a seventh child. Since her husband’s death, the children have not attended school and have often gone hungry.

As a result of their reporting on Afghanistan, McKenzie and Masters hazarded their reputations and risked their livelihoods. Because of what he did there, Roberts-Smith has lost his good name and may lose his liberty. Ali Jan lost his life. Bibi Dhorko lost her husband. Their children lost a father and any hope for a better future. Wasn’t our intervention in Afghanistan intended to have precisely the opposite effect?

The man who murdered Ali Jan for no reason other than that the frightened Afghan smiled at him has been supported through thick and thin by a coterie of some of Australia’s most influential figures – politicians, media proprietors, reporters, shock jocks, institutional heavyweights – who lauded him as an emblem of Anzac manhood. Even now, after Justice Besanko ruled that, on the balance of probabilities, Roberts-Smith was a murderer, a liar, and a war criminal, dismissing his defamation case in its entirety, a noisy minority continues to reject the evidence and defend him. Every nation needs its heroes and the narratives that celebrate their qualities, and in Australia we have a range of them to choose from beyond Anzac. How, as a people, can we continue to countenance a myth that not only invites us to turn a blind eye to murder but encourages us to celebrate its perpetrators?

Comments powered by CComment