- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A black hole

- Article Subtitle: The airbrushing of George Orwell’s reputation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Wifedom is both an immovable and an irresistible book, an object and a force. Anna Funder, the author some years back of the bestselling Stasiland (2003), has written another great and important narrative of oppression and covert suppression, in this case of the first Mrs George Orwell, Eileen O’Shaughnessy (1905–45). The oppression and suppression are or were the work of her liberal and emancipatory husband – the nearest thing we have these days to a lay saint – and of his six (male) biographers. While nowhere a nasty book (what the Americans would call ‘mean’), it’s a kind of St George and the six dwarves. What’s strange is the persistence of the old bromides. In a recent Guardian review of D.J. Taylor’s Orwell: The new life (2023) – the biographer’s second go-around – Blake Morrison refers to ‘the practical Orwell’ and ‘the complaisant Eileen’. He wouldn’t have said either thing if he’d been able to read Funder’s new book.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

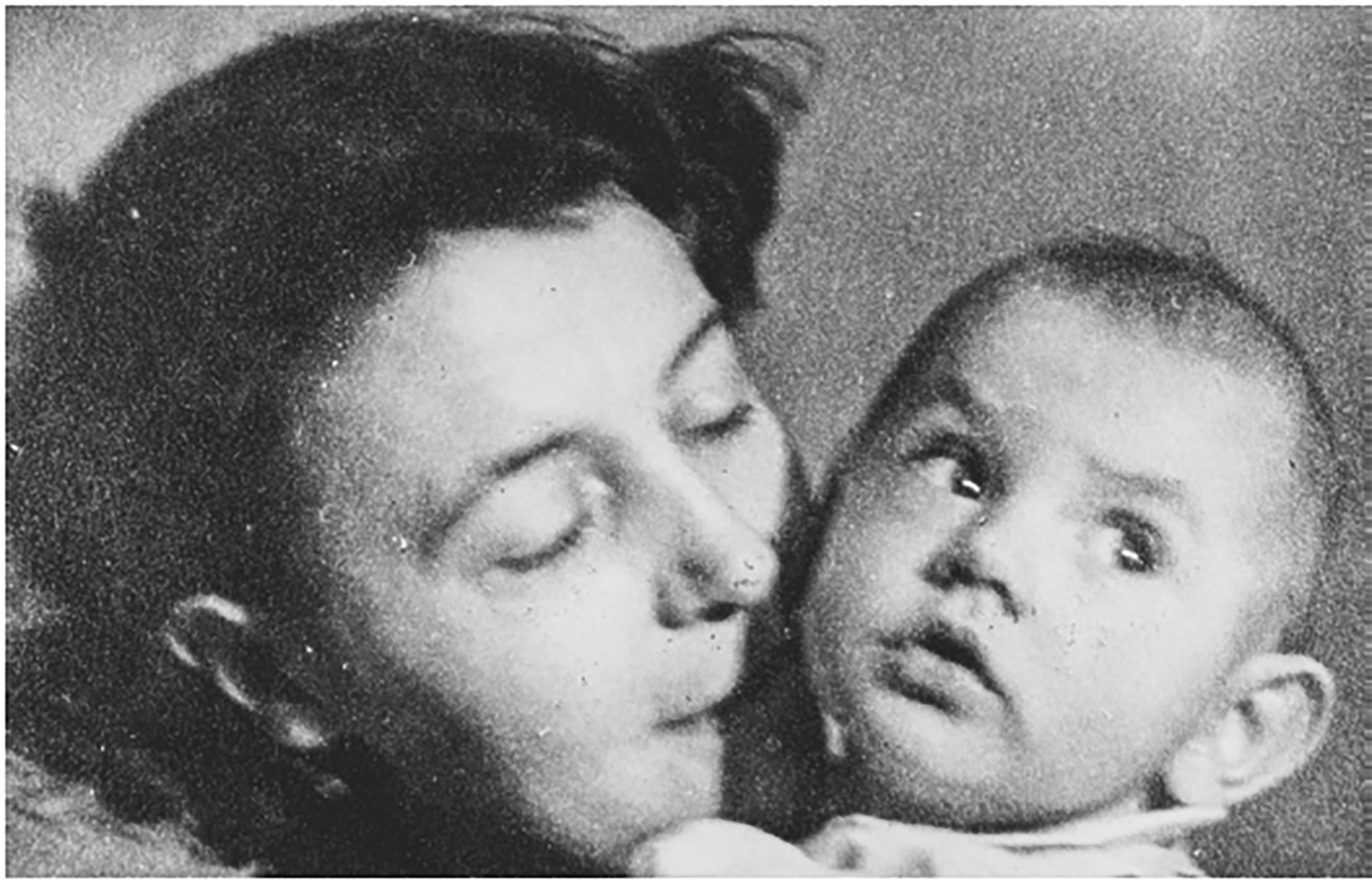

- Article Hero Image Caption: Eileen and Richard, 1944 (from the book under review)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Michael Hofmann reviews 'Wifedom: Mrs Orwell’s invisible life' by Anna Funder

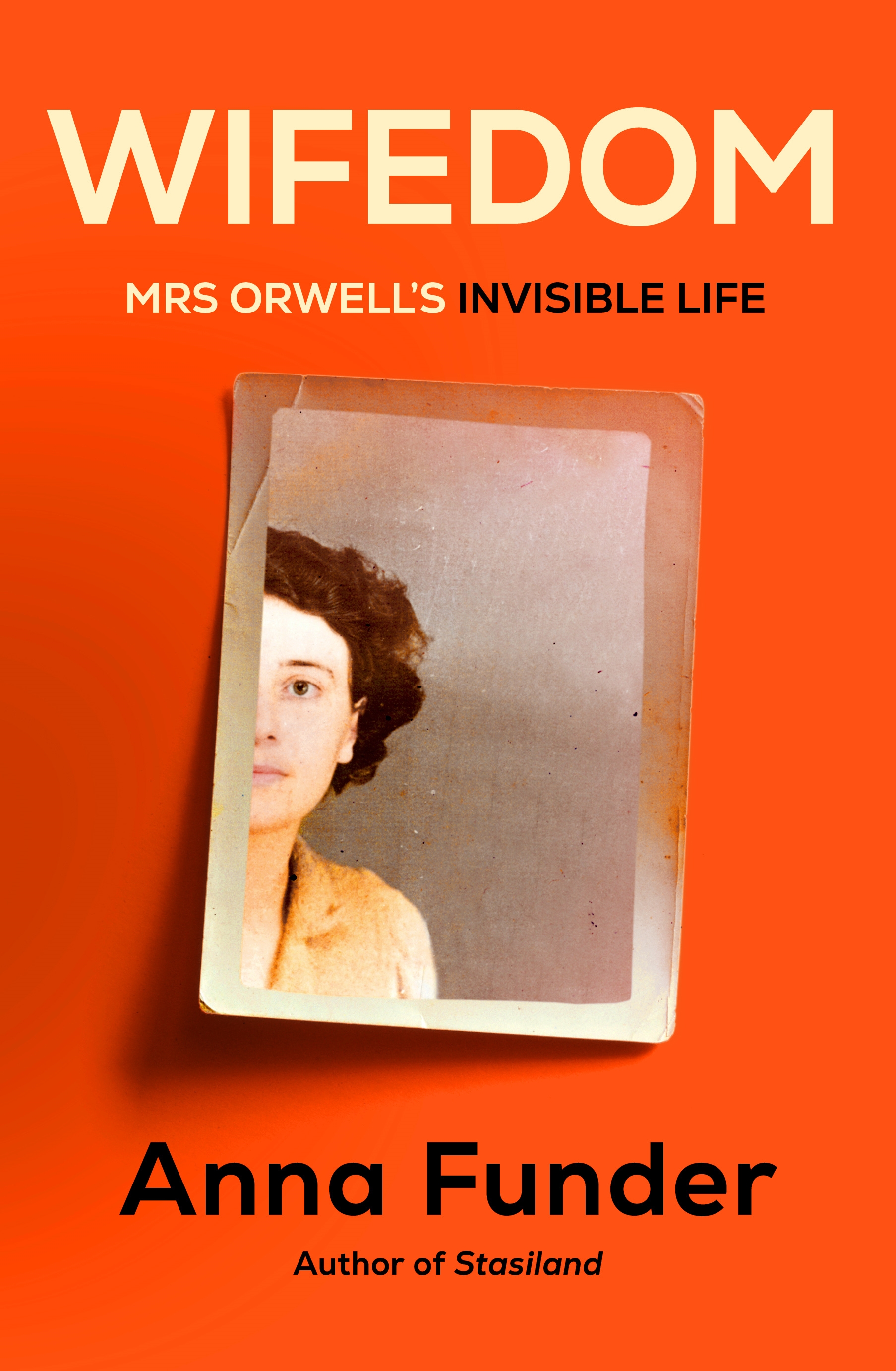

- Book 1 Title: Wifedom

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mrs Orwell's invisible life

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $35 pb, 407 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Change the metaphor. Some books are like soup. Their contents have been together for a long time, macerating, softening. They have exchanged tastes, everything in them tastes of everything else, they are reduced, complex, rich, samey. Wifedom is more like a salad. It seems to take a long time starting (a plus!), has a stuttering, original rhythm, a beguiling way of going along like a book that doesn’t know where it’s going next: short sections of Orwell narrative, accounts of Funder’s research, of her life with her husband and children, present-tense sketches with stage directions (‘she runs her forearm over the seat of the chair, sits’) and scraps of dialogue of how things might have been at moments for the Orwells, checking back to see what the biographers say. Each element has its own savour and freshness, and the continual alteration is bracing, surprising, cleansing.

Funder brings the reader intensely close to both the Orwells at many points: their marriage in 1936 (one of many that he contemplated or proposed); their life together in a damp and primitive cottage in Hertfordshire north of London, or camping with his relatives in Southwold; his Paris (for Down and Out in Paris and London, 1933), his Spain (for Homage to Catalonia, 1938), her Spain, their Morocco (for his health); his employment, her employment; his rich friends offstage, her one friend from Oxford, Norah Myles, whom he never met and whom she may not have seen during her entire marriage, and her half-dozen letters to whom, when they turned up in 2005, prompted Wifedom. His numerous affairs, her probably-not-affairs; their World War II mostly in London; their adoption – he was sterile – of a son, Richard, in 1944; the composition – at her suggestion, and with her help – of Animal Farm (1945); their invalidism together and apart – he had the tuberculosis that took him off in 1950, she suffered from chronic pain and bleeding, and died, alone, under anaesthetic for a long-delayed hysterectomy when she was thirty-nine, done in Newcastle on the cheap, in March 1945.

It’s a sad, affecting story, and one that doesn’t seem especially hard to communicate or to understand. I’ve no reason to suppose that lower standards obtain in the Orwell part of the biographical forest than anywhere else in it, and yet it seems to have been methodically if not wilfully occluded and obscured. Far from cherchez la femme, Eileen seems to have been left as ‘something of a black hole at the centre of Orwell studies’, as one of her husband’s biographers describes her, both in her life and in her posthumous reputation. On the publication of Animal Farm, Funder writes in her best barrister mode:

Once again, as after his marriage, Orwell’s friends are astonished at the change in his work. Richard Rees can’t understand how Orwell has discovered in himself ‘a new vein of fantasy, humor, and tenderness’. His publisher Fred Warburg is stunned by its brilliance. Though just how this ‘writer of rather grey novels, with heroes embodying some aspect of his personal character, had suddenly taken wings and become – a poet’, he cannot fathom. ‘There was,’ he writes, ‘after all, little in Orwell’s previous work to indicate that he was capable of this supreme effort.’ Neither man is able to attribute a cause for this remarkable development.

Reflecting on Eileen’s inexplicable standing (or lack of it), one is driven to the conclusion that, high-minded as he was elsewhere, in his personal life Orwell was a villain abetted by knaves. Wifedom shows her in Barcelona (where she followed him after a few months of marriage), at least as much at risk as George on the front; as far from ‘complaisant’ regarding his affairs; as having supported them both during the Blitz, when she took a job for a couple of years at the Ministry of Information; and as doing almost everything to keep their hardscrabble life going while he knocked off hundreds of articles and wrote books that didn’t sell. Often, there seems almost a reversal of the clichéd or expected gender roles: she is the one who is cool, humorous, level-headed, while he is volatile, fearful, irrational.

Funder is dazzling on the recourses and subterfuges of the biographers, masking their incomprehension or the manifest flaws of their subject, the impersonal constructions, the passive voice. Things get done, but not apparently by anyone, and certainly not by Eileen. ‘“Nobody” is her,’ Funder elucidates. And ‘“We”, she thinks, means me.’ ‘So often, when the sense shimmers, or a metaphor blurs, or a bit of stray Latin or French is introduced, what is being hidden is sexual,’ she observes, and one pictures the biographer squirming. The variable, predatory sexuality that so puzzles and dismays the biographers (‘the shadow of the dark horse,’ she quotes one) is simply that of the English public-school product – unpredictable, unexpected, largely unformed – unrepressing itself.

The one place Funder is downright furious is when Eileen is in hospital, where she is about to die:

The biographers generally ignore Eileen’s fears and her worry about Orwell being angry about the expense of her operation. They like to cite George visiting the sick is a sight infinitely sadder than any disease-ridden wretch in the world as evidence that she didn’t want him to visit her. They use this sentence as if she meant it literally, rather than seeing it for the brave face she was putting on his abandonment. She is even made responsible for him forsaking her: ‘She played the whole thing down,’ writes one biographer, saying “I really don’t think I’m worth the money.”’ There is something horrifying about a woman supplying an excuse for the man who is neglecting her, and his biographers then taking it up and running with it.

Funder quotes a contemporary who knew the couple making the interesting and certainly plausible observation that Orwell ‘was in many ways a very ingenuous and almost stupid man’, and notes: ‘This was too difficult for one biographer, who simply left out the words “almost stupid”.’ The airbrush does its work on Stalinism, and also on the critic of Stalinism. After Eileen’s death, while Orwell is out looking for another wife, he propositions one woman, who turns him down. After a while, he gets around to asking her what she does. ‘I’m governing Germany,’ comes the reply.

Comments powered by CComment