- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

- Custom Article Title: Politics by other means

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Politics by other means

- Article Subtitle: India addresses centuries of national humiliation

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is 1856 in a village near Lucknow, the capital of the northern Indian kingdom of Awadh. Two nawabs, Mir and Mirza, are engrossed in a game of chess, oblivious to the calamity unfolding around them. Satyajit Ray’s 1977 screen adaptation of Munshi Premchand’s short story ‘The Chess Players’ captures the decadence and idleness of Awadh, whose indulgent nobility preferred reciting Urdu poetry, listening to ghazals, and enjoying the sensuous pleasures of the zenana to paying attention to the well-being of their subjects. As Mir and Mirza continue the chess game, their state is annexed by the British on the pretext of maladministration – without a shot being fired.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

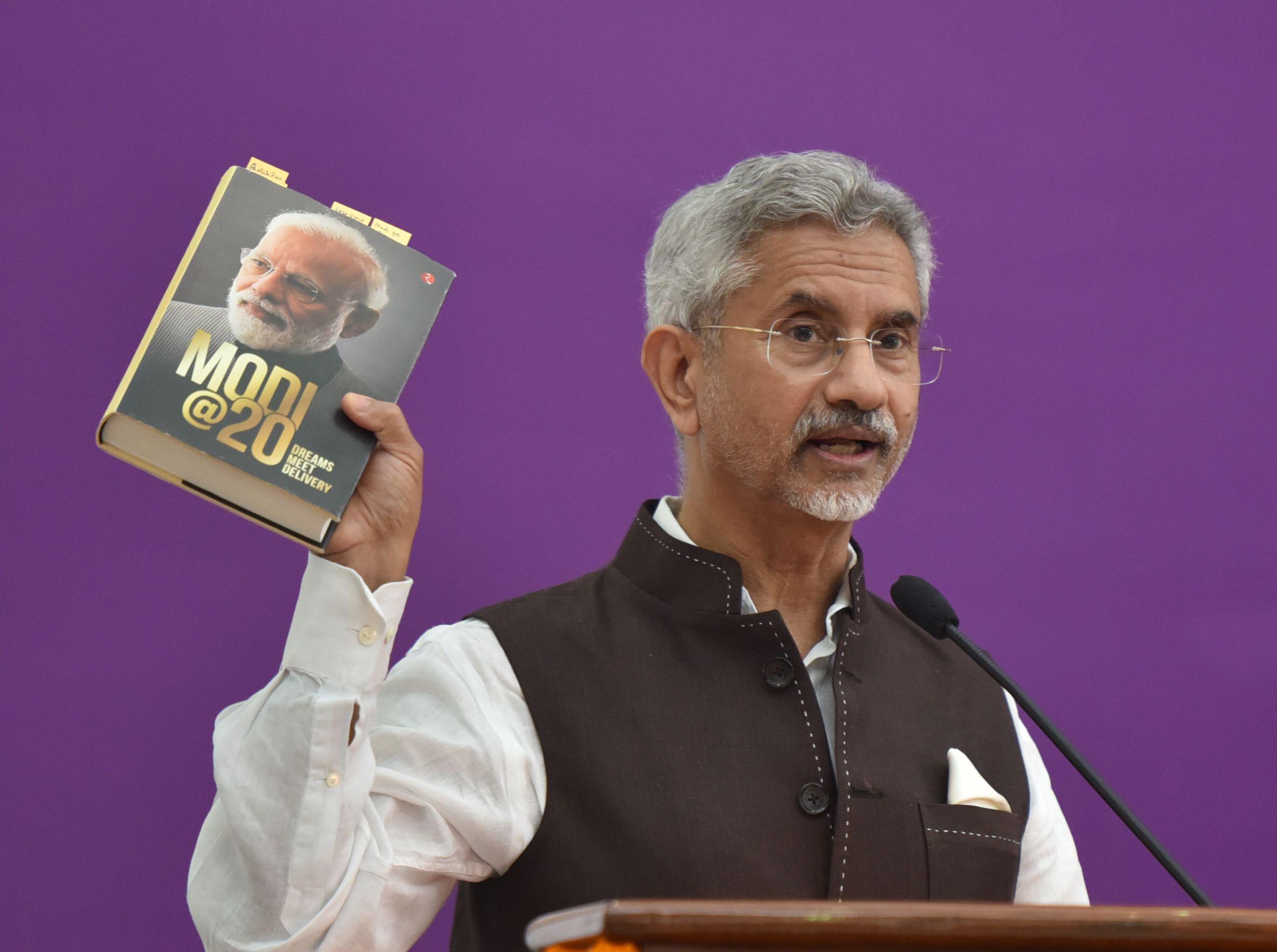

- Article Hero Image Caption: External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar at the University of Delhi, 5 July 2022 (Sonu Mehta/Hindustan Times/Sipa USA/Alamy)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): John Zubrzycki on India's new assertiveness

India’s G20 presidency could not have come at a better time as the country celebrates the seventy-fifth anniversary of its independence. The economy is bounding along at a rate of 6.3 per cent, second only to that of Saudi Arabia among G20 members. Earlier this year, the investment bank Morgan Stanley forecast that India will be the world’s third-largest economy by 2027 and will account for one-fifth of global growth over the next decade. In April, it overtook China as the most populous country in the world, according to UN estimates. The country is now the acknowledged leader of the Global South, setting the agenda on issues such as health, education, bridging the digital divide, food and energy security.

Modi is grasping the opportunity presented by the G20 to establish his credentials as a global statesman and consensus builder. Over his two terms in office, he has skillfully sculptured his appeal to voters on three main pillars: Hindutva, an ideology that espouses the vision of India as a Hindu nation; social welfare programs aimed at meeting the basic needs of all its citizens; and nationalism.

It is the last of these pillars that is most often overlooked when explaining Modi’s success. Having bulldozed his way to power in 2014 by promising to restore India’s place in the world and to make Indians proud of who they are, he has never deviated from that message. In this narrative, India’s presidency of the G20 is celebrated as a personal achievement. Every time an Indian is appointed to head a Fortune 500 company, it is touted as a reflection of the reawakening orchestrated by his government. ‘In the minds of many of his supporters, Modi is a hyper-nationalist who rose to the top from nothing and restored the lost glory of India which had been destroyed by corrupt and lazy leaders,’ writes political commentator Vir Sanghvi. ‘Until the opposition manages to counter his claims in this area, Narendra Modi will remain undefeatable.’

Restoring India’s lost glory on the world stage is where Jaishankar, with his extensive international experience, complements Modi’s grassroots charisma. Dapper and urbane, Jaishankar served as ambassador in the two countries most critical to India’s future – China and the United States – before being offered a ministerial post in 2019. Jaishankar took to his role with gusto; he launched a scathing critique of Western hypocrisy, insisting that now was the time to redress ‘two centuries of national humiliation’ that the West inflicted upon India and the US$45 trillion in value it extracted from the subcontinent. When India’s allies criticised New Delhi for refusing to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, he retorted: ‘Europe has to grow out of the mindset that Europe’s problems are the world’s problems.’

Standing up to Beijing and exploiting Western fears about China’s increasing belligerence and influence is crucial to India’s strategy of playing off the great powers and carving a new global identity. China has replaced the Raj as India’s main adversary. The nuclear-armed Asian giants share a largely disputed 3,488-kilometre border that has been the site of numerous skirmishes and one full-blown war.

Like Mir and Mirza a century earlier, Nehru was too busy romanticising India’s special relationship with China to take seriously the People’s Liberation Army’s build-up on his country’s vulnerable north-eastern border. India’s defeat in the 1962 Sino-Indian war remains a national humiliation that Jaishankar is determined will never be repeated. A long-standing policy of rapprochement was abandoned in 2020 after a Chinese incursion in Ladakh led to hand-to-hand combat that left twenty Indian soldiers dead. New Delhi responded by banning companies, including Huawei, from investing in India and by blocking Chinese apps such as TikTok and dozens of other mobile apps. Tensions along the Himalayan frontier remain high.

Central to Jaishankar’s strategy of plurilateralism has been the revival of alliances such as the Quad, which groups India, the United States, Australia, and Japan. Ignoring criticism from Beijing that the grouping is a ‘mini-NATO’, India held a G20 foreign minister summit and Quad meeting almost simultaneously in March 2023. India has also strengthened its bilateral defence arrangements with Australia by instituting a regular calendar of naval exercises, strategic dialogues, and training exchanges.

By playing the China card, India has managed to blunt international criticism of its stance on Ukraine. New Delhi’s dependence on Moscow for most of its defence imports and its appetite for cheap crude oil, imports of which have risen thirty-fold since the invasion began, are partially behind India’s muted response to the invasion. More significant is the fundamental shift in Indian realpolitik, namely its perceived right to act in its own self-interest in a highly fluid global order. As Jaishankar writes in his book, ‘What will emerge is a more complex architecture, characterised by different degrees of competition, convergence and coordination. It will be like playing expanded Chinese Checkers, including with some who are still arguing over the rules.’

This new assertiveness on the global stage is being mirrored on the domestic front. India is using its G20 presidency to invest heavily in promoting itself as the ‘mother of democracies’, but the reality is somewhat different. In early 2023, income tax officials raided the offices of the BBC in New Delhi. The raid came shortly after the broadcaster aired a documentary on Modi’s alleged complicity in communal violence in Gujarat in 2002 that led to the deaths of thousands of Muslims. The documentary was banned in India. Students who gathered at university campuses to defy the prohibition by watching it on their phones and at private screenings were arrested.

In March 2023, Congress Party leader Rahul Gandhi, the fourth member of the Nehru–Gandhi dynasty to lead the party, was stripped of his parliamentary seat after being convicted of defaming the prime minister in a 2019 campaign trail remark. Legal experts slammed the case as being politically motivated, linking it to Gandhi’s trenchant attacks on Modi’s close links with Gautam Adani. The Gujarati-born industrialist was ranked the world’s third-richest person until $US125 billion was wiped off his net worth following a scathing January 2023 report by short-seller Hindenburg Research, accusing his group of ‘brazen stock manipulation and accounting fraud’.

Citing the ‘increasing harassment of journalists, nongovernmental organizations, and other government critics’, and the ongoing social and economic marginalisation of Muslims, untouchables and tribal groups, Freedom House in 2023 scored India’s democratic ranking as ‘partly free’ for the third year in a row.

Such criticisms are unlikely to trouble India’s leaders. When asked about the ban on the BBC documentary, Jaishankar responded by saying it was not about freedom of speech but politics. ‘There is a phrase called “war by other means”. This is politics by other means.’ Nor is India’s sense of its exceptionalism, or its belief that its moment has finally arrived, going to cloud apparent contradictions in its foreign policy. While India is strengthening ties with the Quad, it is also engaging with the China-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which is aimed at counterbalancing US influence in Eurasia.

China might be India’s main strategic rival, but as Jaishankar writes in his book, the ability of the two countries to work together ‘could determine the Asian century’. There is also much that India can learn from China, including most importantly that ‘demonstrating global relevance [is] the surest way of earning the world’s respect’. Jaishankar is not shy about using forums such as the UN General Assembly to remind the world that India was ‘pillaged by centuries of foreign attacks and colonialism’, but he is not apologetic about drawing closer to the West.

‘Will the world continue to define India, or will India now define itself?’ Jaishankar asks. His answer is self-evident: ‘The world is today required to come to terms with this changing India.’ It is a mantra that global leaders would be foolish to forget.

This is the first in a series of articles to be supported by Peter McMullin AM via the Good Business Foundation. Featured articles will cover a range of subjects: human rights, refugees, whistleblowers, and nations in our region.

Comments powered by CComment