- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A bon vivant's life

- Article Subtitle: The long awaited biography

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

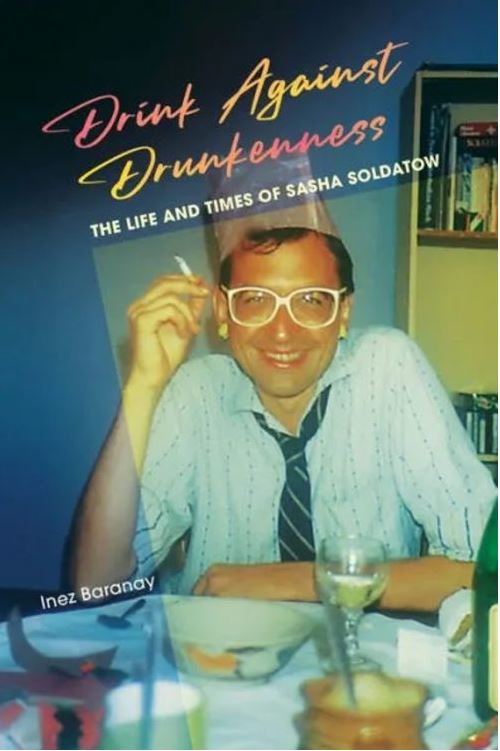

Sasha Soldatow was a writer, gay activist, member of the Sydney Push, party animal, and bon vivant with legions of friends. In Drink Against Drunkenness, Inez Baranay maps the life like an archaeologist’s dig, though we are looking into the recent past (Soldatow died in 2006, not yet sixty). A fall in the icy streets of Moscow, in which his hip was broken and subsequently badly reset, heralded a steep decline; his alcoholism grew apace, and many of his friends tired of him. It was a sad end, yet he had a life full of daring: avant-garde writing and living freely as a gay man in a still repressive age.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Susan Varga reviews 'Drink Against Drunkenness: The life and times of Sasha Soldatow' by Inez Baranay

- Book 1 Title: Drink Against Drunkenness

- Book 1 Subtitle: The life and times of Sasha Soldatow

- Book 1 Biblio: Local Times Publishing, $39.99 pb, 506 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Drink Against Drunkenness is a big, dense book, but never obscure. At first it feels untidy, flitting in and out of diverse subjects, sometimes rounding back to them, with a loose chronology. A couple of early chapters about early group endeavours have little interest and some chapter headings and subheadings yield no obvious meaning until the reader gets used to Baranay’s free-flowing style. Then it becomes a lively, often gripping read. The early chapters are full of parties, lovers, alternative publications, and gender-bending performances, poems (the most notable, the scurrilous, funny ‘The Adventures of Rock-n-Roll Sally’), and pamphlets like the influential What is this Gay Community Shit?

Soldatow did a four-year stint as a subtitle writer at SBS, then a hotbed of poets and ‘ethnics’ needing to pay the rent. It was a lively atmosphere where Soldatow excelled. Around this time, he also wrote a scholarly analysis of the anarchist poet Harry Hooton, the love of Margaret Fink’s life – a landmark book for Australian culture. Then Soldatow and Bruce Pulsford fell in love. Bruce was ten years younger, a lawyer, good-looking, shy, and entranced by the exotic Soldatow. The affair ended quite early but Bruce was the great love of his life; he remained his most loyal friend and supporter until Soldatow’s death.

Soldatow’s first collection of short stories with its cheeky title Private, Do Not Open (1987) appeared when he was forty. It was well reviewed. (Those were the halcyon, far-off days when new left-of-field authors were given space and taken seriously in the weekend papers.)

Soldatow was gradually making his name, but never felt accepted by the broader literary world. He famously took the Australia Council to court in 1990 for never giving him a well-deserved grant after sixteen years of applications. He actually won his case with the aid of his canny barrister, John Basten. Next year a grant materialised and he went to Vietnam on it, declaring, ‘It won’t stop me whingeing.’ It never did.

Soldatow’s time in Russia was a turning point in his life. Long after they had a youthful affair, David Marr re-entered his life in Moscow. Then Marr went back to Sydney, leaving Soldatow broken-hearted. Worse, he was unable to find his place as a Russian; his romantic idea of his own Russianness was shattered by the harsh realities of Moscow life just before the USSR fell. He finally understood that he was an Australian, but he could not grasp that living between two cultures could be a fecund place for a writer; the outsider’s observing eye, a slight distance.

Nevertheless, two of his best books came after the Russian interlude. Jump Cuts (1996), with Christos Tsiolkas, was a lively exchange between two generations of migrant gay men: Greek and Russian. Mayakovsky in Bondi (1993) shows his best qualities as a writer: innovative in form, with some angelic phrasing, bravery of subject matter, and a deep sadness from his Russian ancestors. The last piece, his wonderful translation of Anna Akhmatova’s Requiem, shows his erudition and empathy.

But Soldatow carried on drinking and partying. His oeuvre was slight but not in originality or quality. Inez Baranay is his ideal biographer. Knowing Soldatow as a friend, yet having lived away from Australia for many years, she can maintain her distance. Drink Against Drunkenness is both affectionate and forensic, with generous dollops of interviews with friends and associates, along with Soldatow’s letters and drawings. Baranay has captured an important and vivid era of Australian cultural life. You can read the book in two ways – picking subjects of interest, or following the whole rich panoply that was Sasha Soldatow.

Comments powered by CComment