- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: An ever-rattling mind

- Article Subtitle: A short-lived, influential choreographer

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

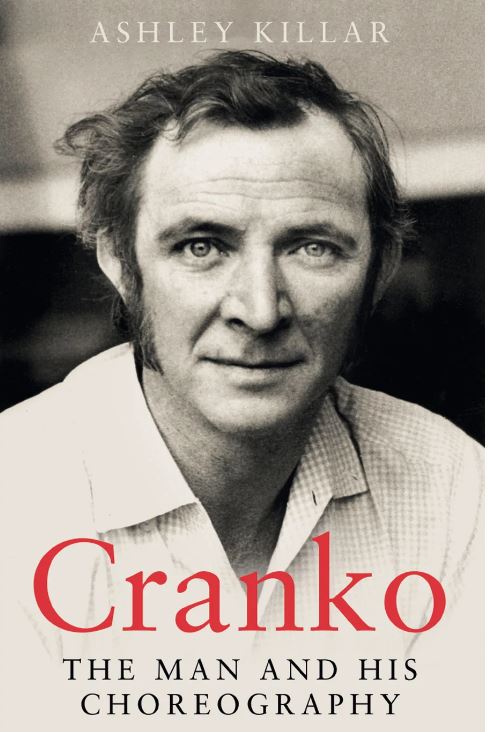

Reading Ashley Killar’s compelling biography, Cranko: The man and his choreography, feels like studying the modernisation of ballet in three countries, the way ballet eats up lives as often as it forms families of peers and lovers, and the unending devotion required for creativity to flourish. It is pleasing to learn how a determined man with an ever-rattling mind, backed by a calm, philosophical manager, could challenge opera house dominance to make the Stuttgart Ballet an independent entity, with its own school supported by a philanthropic institution named after the city’s first ballet master of the 1750s, Jean-Georges Noverre, whom David Garrick called ‘the Shakespeare of the dance’.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Lee Christofis reviews 'Cranko: The man and his choreography' by Ashley Killar

- Book 1 Title: Cranko

- Book 1 Subtitle: The man and his choreography

- Book 1 Biblio: Matador, £24.95 pb, 207 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

His father, Herbert Cranko, supported his endeavours, finding new mentors and encouraging his hunger for theatre and ballet, despite his wife’s initial disapproval. In time, working hard as a student, then as a member of Sadlers Wells Theatre Ballet (now the Royal Ballet), Cranko was mentored by their insightful ballet mistress, Peggy van Praagh, and observed two Diaghilev favourites, Tamara Karsavina and Léonide Massine, coaching dancers for opening nights. In thirteen years Cranko created some forty ballets for the Wells, Royal Ballet and Royal Opera companies, including Pineapple Poll, a romantic comedy by young Australian conductor Charles Mackerras, to a pastiche from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Savoy Operas, and The Prince of the Pagodas, with new music by Benjamin Britten infused with Balinese gamelans. Many more productions would follow with many designers, beginning with his first boyfriend, Hanns Ebensten.

By 1959, still mourning his father, who had died the previous year, Cranko was burning out and soon became persona non grata. Several flops, and the sniping at the Royal Ballet, fuelled by artistic director Ninette de Valois, had depressed him, as did his shaming for public procuring. He pleaded guilty, was fined, and released. Collectively these burdens drove Cranko from England to Stuttgart, where he had friends and the potential to reposition himself.

Ashley Killar is another Royal Ballet School graduate. In 1962, he began his peripatetic career at the Stuttgart Ballet, where Cranko was expanding the repertoire and promoting, expressionism, and a culturally diverse ensemble. His first three-act ballet Romeo and Juliet was in its final rehearsal stage. Battling snowstorms, the ‘green’ Killar arrived just in time to watch the rehearsal and to pass his audition the following day. His crystalline memories of those weeks, and the success of Romeo, are carefully laid out, juxtaposing the man who needed a family of artists to care for him with the man determined to revolutionise the world’s conventional expectations, who shaped every one of his dancers to be better and braver in every ballet and still be themselves, no matter how delicate or strong they were.

Privately, Cranko was dreadfully lonely. The early years of drinking into the night with dancers and friends in the local Greek Café had passed as his workload expanded. Without his general manager, Dr Walter Schäfer, his personal manager Dieter Gräfe, and all his principals behind him, he would not have lasted long. Critics in Germany were as caustic as the British, until they appreciated Cranko’s agenda. In the United States, Balanchine and the New Yorker’s spiky Arlene Croce dumped on him, while showbiz potentate Sol Hurok provided the Stuttgart dancers with many stages to satisfy the audiences who clamoured for them.

Depression and fatigue dominated Cranko’s last years. Killar is sensitive about the early friendships that collapsed. This was followed by the suicide of his music arranger, Kurt-Heinz Stolze, and the death of his adored stepmother. Even artists John Piper and his wife, Myfanwy, his first ‘family’ away from home, faded from his life.

In a more analytic mode, Killar investigates selected ballets to understand how Cranko succeeded or failed to achieve his expectations. As an observant insider and experienced director, Killar is well placed to put each work in context. A collection of letters, like the political timeline in the repertoire catalogue, illustrate the conditions in which each work was made. This may seem rather clinical, but it is greatly illuminating and reveals how Cranko changed the aesthetics of European ballet and produced a new breed of gifted choreographers, dancers, and designers.

Comments powered by CComment