- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Human constellations

- Article Subtitle: Paul Dalgarno’s chatty ghost

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When a book takes its title from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, you can expect the shock of something supernatural. But although Paul Dalgarno’s A Country of Eternal Light is narrated by a dead woman, there is little here to horrify.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Jennifer Mills reviews 'A Country of Eternal Light' by Paul Dalgarno

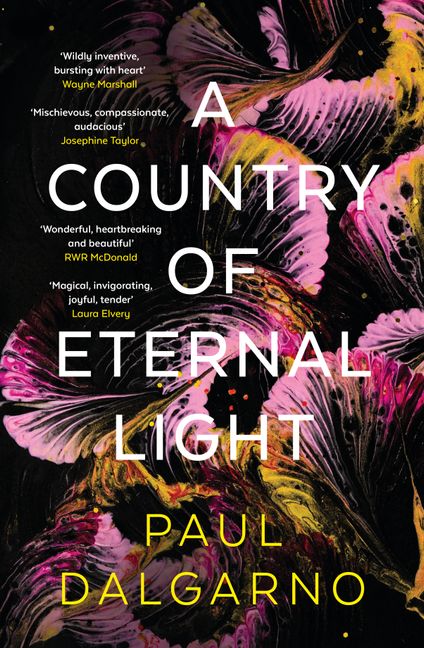

- Book 1 Title: A Country of Eternal Light

- Book 1 Biblio: Fourth Estate, $32.99 pb, 311 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Dalgarno’s strong ear for dialogue and his direct style are a natural fit for domestic realism, so it is encouraging that he has set himself the challenge of writing in a slightly different register here. But even though it looks at death, A Country of Eternal Light remains more interested in the living. This novel is suffused with nostalgia for a Scottish childhood. The textures of a range of times and places – Scotland, Australia, Spain – are carefully interspersed and often beautifully drawn. The emotions are bigger, the scenes more freighted, as Dalgarno tackles heavier subject matter. This book about grief and loss, denial and faith, stays steeped in the dailiness of human existence, tethered to the real.

Dalgarno is primarily interested in families, in the feelings that are fired up or contained by their structures, in how those structures support or condemn their members. He comes across as psychologically literate, with characters informed by therapeutic models. In these models, we are who we are in constellations with each other, with narratives, and with our pasts.

As in Poly, the daily life of parenting provides the author with endless material. Dalgarno writes the anxiety and delight of raising young children beautifully, and it’s that energy that hums through this book, leading us to the puzzle’s eventual resolution. There must be a resolution, for this ghost wants to be put at rest.

All ghost stories are about justice, and A Country of Eternal Light fulfils the brief, with the narrative culminating towards a reckoning with past wrongs – nothing so dangerous as evil, but the kind of human failure that steers a life off track and can quickly spin a family out of its orbit. The lived consequences of this are tragic for Margaret’s family, with each character hurtling into his or her own variation of traumatic replay.

Like the tales Margaret’s daughter Rachel tells her own children, stories that are a form of play therapy for herself and the children, A Country of Eternal Light has a meandering structure. It can seem sprawling, like her husband’s mind: ‘no beginning or end, a story snagged in medias res’. This can slow the compact novel’s pace, and repeat clues, making the twist a little predictable.

However, the success of a first-person narration comes down to character, and Margaret’s company is a pleasure. Disarmingly direct in a late-life (well, after-life), no-fucks-left way, she’s honest with the reader, even when she’s not being honest with herself. It is always good to meet an older woman in fiction who remains complex and human and flawed, never a victim of her life and never a villain. She is fully embodied to such an extent that she sometimes forgets she doesn’t have a body at all.

There are some irritants, such as the tendency to sing-song in the language, paired words (dropsical/popsicle; nemesis/emesis; an oxcart of oxytocin, and so on) that disrupt the storytelling and add nothing to a sense of character. But when she speaks clearly, the observant, reflective Margaret has a winning combination of carelessness and meticulousness, humour and sorrow. She can be very funny.

Though many fragments from Frankenstein are peppered throughout this novel, the narrative veers away from the monstrous, homing back to the domestic scale and the more forgivable, quotidian crimes of neglect, bitterness, and failure. The idea that the stories we tell are not what they seem is not new, but it is well articulated. That ‘grief drives us out of our minds’ is true enough, even if this novel is ruled by a simpler moral logic, the nineteenth-century reference point perhaps more Charles Dickens than Mary Shelley.

Dalgarno, who works as a journalist and has two books out this year, has no shortage of energy. He has a flair for emotional nuance and much to offer in the way of feeling. A Country of Eternal Light invites the reader to suspend their cynicism and allow the heartstrings to be played. Sentiment steers the reader away from difficult waters, reaching for something very lifelike, but ultimately cleansed of real danger. Dalgarno conjures a tender and warm-hearted world, where – if you can believe it – some light remains in grief, and no one ever really disappears

Comments powered by CComment