- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

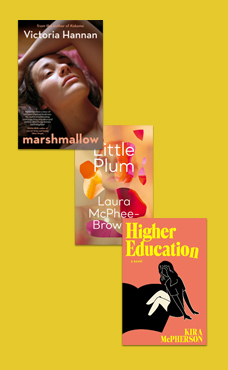

- Custom Article Title: Three new novels

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mysteries and motivations

- Article Subtitle: Three new novels

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A marshmallow is a common confectionery, white and pink, made of gelatin, sugar, and water. We put them in hot chocolate, toast them over campfires. Marshmallow is also a plant, Althea officinalis, containing a jelly-like substance which has been used for medicinal purposes as far back as the time of Ancient Egypt. A marshmallow can also describe someone who is soft to a fault, even vulnerable. That there might be anything approaching complexity linked to this word is unlikely, but by the end of Victoria Hannan’s second novel, Marshmallow (Hachette, $29.99 pb, 292 pp), it is obvious that something as apparently innocuous as that confectionery and medicinal ingredient can have many implications; the intriguing title is an early indication that much will be going on, none of it straightforward.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Debra Adelaide reviews 'Marshmallow' by Victoria Hannan, 'Higher Education' by Kira McPherson, and 'Little Plum' by Laura McPhee-Browne

- Book 1 Title: Marshmallow

- Book 1 Biblio: Hachette, $29.99 pb, 292 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Title: Higher Education

- Book 2 Biblio: Ultimo Press, $34.99 pb, 323 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 3 Title: Little Plum

- Book 3 Biblio: Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 256 pp

- Book 3 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 3 Cover (800 x 1200):

The key event, the one brief but crucial action that everything else leans towards, which is in the back, middle, and front of the minds of the characters as they go about their respective business, is revealed perfectly (if that is the right word for such a tragedy) about three-quarters of the way through. We all know that people grieve in different ways, and Hannan confronts these miseries head on. For instance, Annie, the mother of the dead boy, is uprooting her beloved front garden the day before his birthday anniversary; the father, Nathan, is off in his own world, addicted to online card games and avoiding work, as well as handling the selfish cold grief of his materialistic parents. Neither is capable of speaking their child’s name, for obvious reasons, and it is not articulated until late in the novel. ‘Toby,’ Annie finally says, ‘I’m going to make Toby a birthday breakfast.’ It is a heartbreaking moment.

But why should the novel commence not with the parents but with a friend? We meet Al as he is gripped by a Friday morning panic attack anticipating the next day, which ‘would be a year since it happened’. Consumed with anxiety, he obsessively revisits the death of a friend when he was a teenager, then googles news reports of the recent incident. Distanced from his partner, Claire, who is secretly considering accepting a new job in another city, Al is a consummate emotional mess, but as the past unfolds via backstory, it becomes clear why.

Why too should the one remaining friend who was there on the day of the incident, Ev, be the most supportive, practical, and functional of the group? Especially when on the surface she feels the most responsible for the death of the child?

The answer is that there is no ‘how to’ book, brochure, or set of rules for grief, especially when it comes to losing a child. There are no correct words. No script. One of my litmus tests for a good novel is that I learn something yet never suspect the author is trying to instruct me. The great gift of this thoughtful, tender, and moving novel is to expose the maddening emotional effect of suffering, and the illogical, individual, and thus unique way people deal with their common experience of grief. The next time I consume a marshmallow I will pause and reflect on this.

Comparisons may be odious, but here they are unavoidable given the brief. So, by contrast, while Kira McPherson’s first novel, Higher Education (Ultimo Press, $34.99 pb, 323 pp), offers a promising idea, problems of style and structure occur from the start. The protagonist Sam is a law student, struggling with her independence, her sexuality, and her family. So far so good – the coming-of-age narrative is always ripe for exploitation. While academically a high achiever, Sam also feels constrained by her suburban working-class background and thus pursues a mentorship with a woman from a different class, understanding that this will validate her choices, possibly even propel her into insider status in the legal world.

Though promoted as ‘deeply funny’, Higher Education is mostly deadly serious, distinguished by a combination of overthinking as well as limitations of thought. The former is demonstrated in overlong scenes, for example tutorial sessions that might have been intellectually engaging in real life but on the page are the kiss of death, or intense scrutiny of interactions that simply try too hard; the latter is seen in the consistently short sentences and short paragraphs that prohibit the development of an idea.

Even without the unaffected authority of Marshmallow as a benchmark, Higher Education reads clunkily. The extreme brevity of sentences and paragraphs is exacerbated when the present tense of the main narrative kicks in. This is a shame because there are treasures here, flashes of insight within the unnecessarily detailed scenes and exhausting blow-by-blow dialogue. For instance, the complex dynamics of Sam, her legal mentor, Julia, and her husband, Anselm, are wryly noted: ‘Something that felt unknowable to Sam becomes clear … Anselm and Julia can perform their relationship for her, and she can change it through the act of observation.’ The novel also provides a lively and engaging domestic account of Sam’s family, with her menacing stepfather in particular depicted with great conviction.

My first reading of Laura McPhee-Browne’s Little Plum (Text Publishing, $32.99 pb, 256 pp) was quick and I admit to returning to it reluctantly. I am not an anti-present-tense crusader by any means, but here a deflated style adds nothing to a lean story. The protagonist, Coral, has a destiny defined by her name – her mother is called Topaz, her grandmother Beryl, her best friend Amber – and the story involves a gemstone as a symbolic token. A reporter for a community newspaper, Coral meets Jasper (yes) while on assignment at a crime scene. Soon Coral is pregnant and decides not to inform Jasper or to see him again, yet it is never indicated why she quickly flips from attraction to rejection.

The bulk of the novel tracks the pregnancy with Coral’s curiosity about the creature growing inside her, the ‘little plum’ (provided by an epigraph from Anne Sexton’s poem ‘Hansel and Gretel’), mixed with emotional indifference. Motivations remain unexamined, access to the characters’ interior lives is limited, actions are told rather than shown, distancing us from the story, and while Coral is anxious and naïve, this does not explain the childlike voice of the prose. Towards the end, when a nurse tells Coral her baby is a boy, she ‘doesn’t know what this means’. But she names the baby Flint, presumably tying up the novel’s mineral theme. I was puzzled too.

Comments powered by CComment