- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: House and garden

- Article Subtitle: Examining Menzies’ early life and career

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

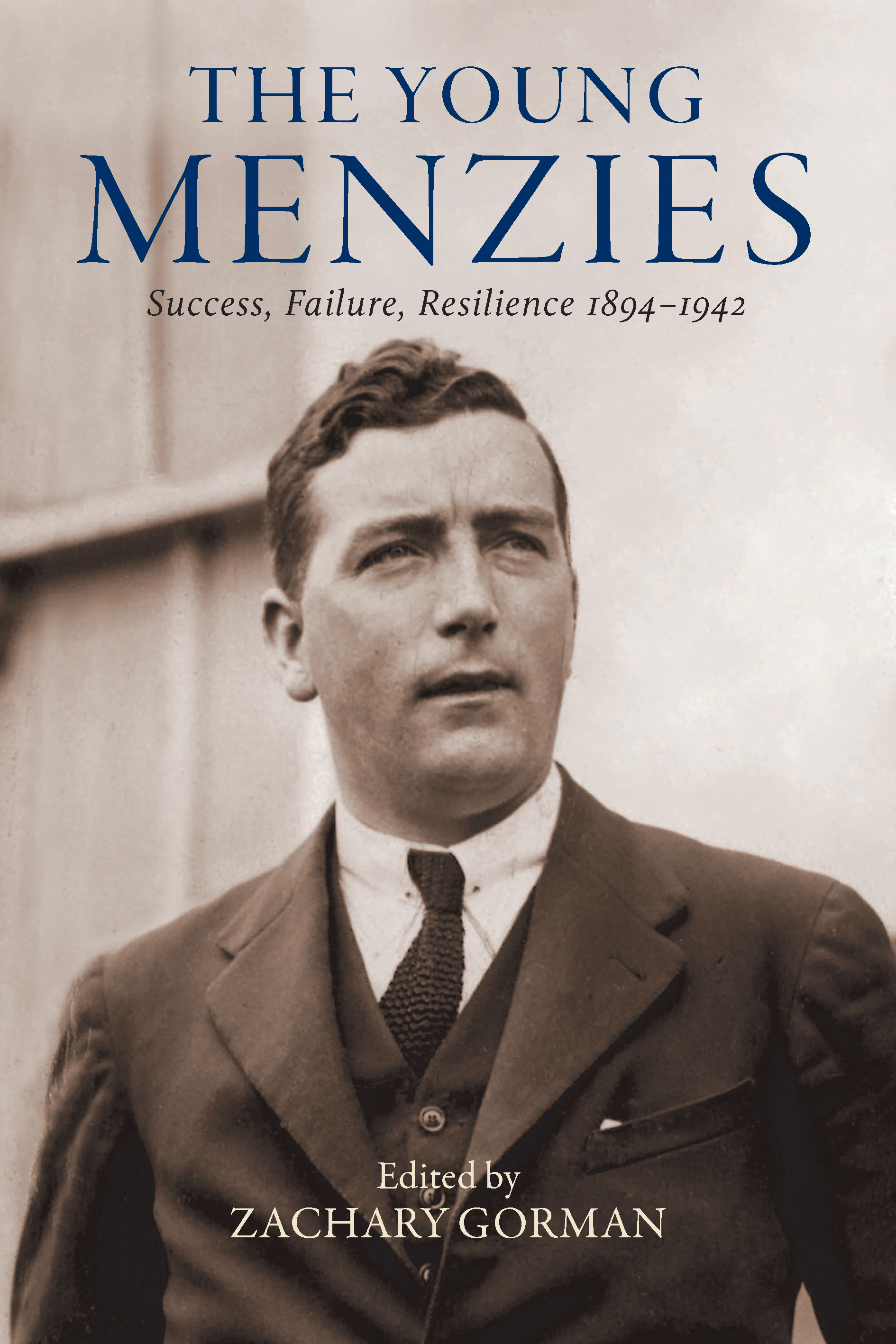

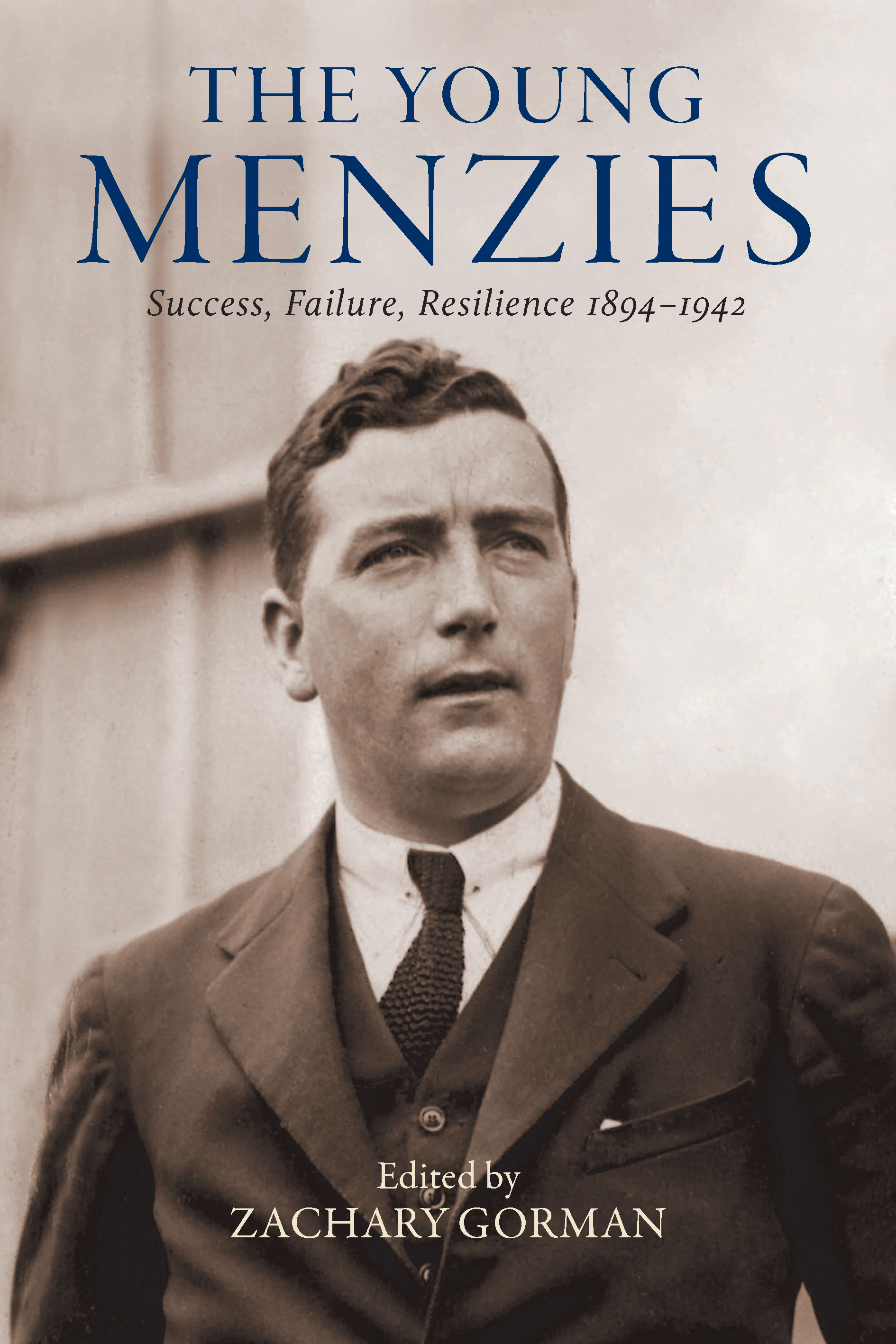

Robert Menzies retired as prime minister more than fifty-three years ago and died in 1978, yet he remains not just a dominant figure in Australian political history but a strong influence on modern political affairs. As Zachary Gorman, editor of this latest book on Menzies, argues, ‘it has become almost a cliché to say that he built or at least shaped and moulded modern Australia’. He created the Liberal Party that has governed Australia for fifty of the past seventy-three years, and modern Liberal politicians still draw on Menzies’ ideals.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

- Article Hero Image Caption: The War Cabinet in session in the Old Legislative Council Chamber, Queensland Parliament, Brisbane c.1940 (State Library Victoria reference H99.201/2584)

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): David Horner reviews 'The Young Menzies: Success, failure, resilience 1894–1942', edited by Zachary Gorman

- Book 1 Title: The Young Menzies

- Book 1 Subtitle: Success, failure, resilience 1894–1942

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, $39.99 hb, 224 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

The co-authors of the chapter on Menzies and the law – James Edelman, a Justice of the High Court of Australia, and Angela Kittikhoun, a lawyer – bring deep understanding of legal affairs. They argue that it is often overlooked that despite a relatively brief legal career before he entered the Victorian state parliament in 1928, Menzies made an enormous contribution to law in Australia.

The chapter on Menzies’ promotion of education is by Associate Professor Greg Melleuish from the University of Wollongong, author and co-author of books on liberalism and Menzies. Melleuish argues that Menzies believed that good education, particularly in the humanities, was crucial for the survival of democracy. In this era of ‘fake news’, it is relevant to note Menzies’ view that: ‘The new ambition was to breed a race of people to whom leisure was the chief end of life and the insistence upon a standard of accuracy abhorrent.’

The analysis of Menzies’ debt to Deakinite Liberalism is by Judith Brett, who brings special expertise as the author of a book on Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’ and another on Alfred Deakin. Brett suggests that the sort of liberal philosophy expounded by Menzies owed much to that put forward by Deakin four decades earlier, and that possibly ‘Menzies looked to Deakin as a role model for the well-lived Liberal political life’.

The chapter on how the Presbyterian faith of the young Menzies nourished his philosophy of liberalism is by David Furse-Roberts, a research fellow at the Institute. Menzies’ advocacy of the individualistic ethic of the Liberal Party was rooted in the biblical concept of being ‘my brother’s keeper’, whereby individuals took responsibility for the welfare of their neighbours. At the same time, Menzies took an ecumenical approach that transcended the sectarian divide, causing dismay in his strict Protestant family.

The chapter on peace and war by Anne Henderson, deputy director of the conservative Sydney Institute, is to some extent deceptive. It is not about Menzies’ leadership during the first two years of World War II, but rather is a defence of Menzies’ attitude to appeasement before the war. As the author of biographies of Enid and Joseph Lyons, Henderson understands the politics of the 1930s. More importantly, in her book Menzies at War (2014) she made a strong case that Menzies’ achievements as war leader were far more substantial than other authors have allowed. She might at least have discussed Bramston’s claim (in his own book) that in September 1939 Menzies told the high commissioner in London that ‘nobody really cares a damn about Poland’ and that for years he sought to keep these embarrassing views hidden from researchers. Unfortunately, this most important period of Menzies’ life before 1942 is not examined in any chapter.

Professor Frank Bongiorno of the Australian National University has written extensively on labour politics and Australian politics in general. His chapter examines the surprisingly cordial relationship between Menzies and the wartime Labor prime minister, John Curtin, which says much about the character of both men and the nature of politics in a different era.

The central theme of the book is that Menzies was a man of intellect and reflection who developed a broad philosophy of politics based on principles rather than short-term political gain. In their chapter on Menzies as a ‘learning leader’, Scott Prasser and the late Dr Graeme Starr remind us that essentially Menzies was still a politician who knew that to implement his policies he needed to win at the ballot box. Starr was a former director of the New South Wales Liberal Party and author of several substantial books on Liberal politics. Prasser is a senior fellow in the Liberal think tank, the Centre for Independent Studies, and was a senior political adviser to federal Liberal government ministers.

The final chapter looks at Menzies’ ‘Forgotten People’ radio talks, in which he declared that ‘one of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours’. The author, Nick Cater, executive director of the Liberal think tank, the Menzies Research Centre, argues that with this philosophy the Menzies government of the 1950s and 1960s sought to provide opportunities for Australians to become homeowners – a successful policy that shaped modern Australia.

The fact that many authors are conservative commentators does not invalidate their views. This is an engaging book that makes a further and contemporary contribution to our understanding of Australia’s longest-serving prime minister. It raises the important question of what sort of intellect and political philosophy modern-day prime ministers bring to their task.

Comments powered by CComment