- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Fielding among potatoes

- Article Subtitle: A ripping cricket yarn

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

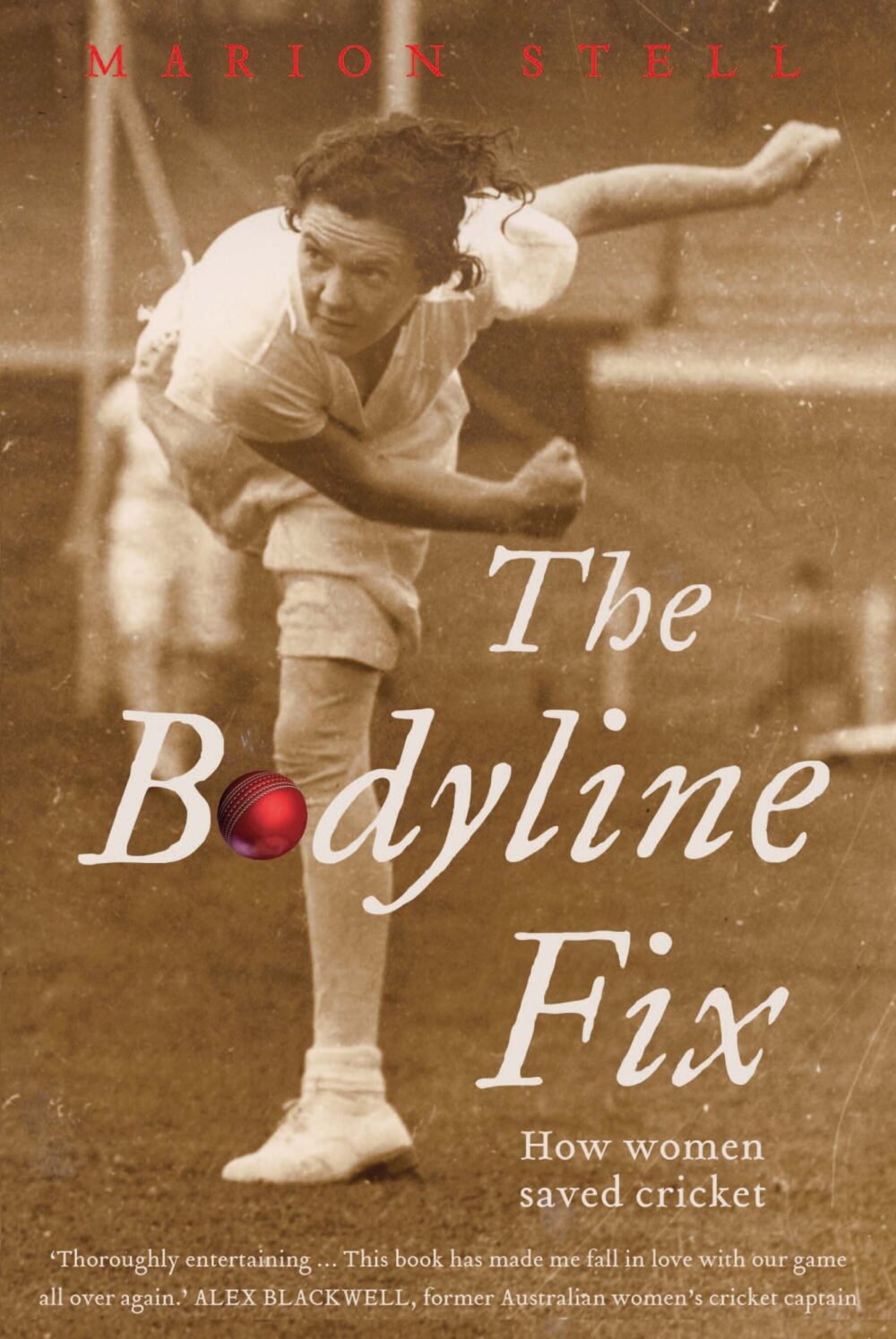

At the conclusion of the third women’s cricket test against England in 1935, Victorian all-rounder Nance Clements souvenired her name plate from the Melbourne Cricket Ground scoreboard. What she discovered on the reverse side of the plate, as Marion Stell recounts in The Bodyline Fix: How women saved cricket, was the name Larwood.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Diane Stubbings reviews 'The Bodyline Fix: How women saved cricket' by Marion Stell

- Book 1 Title: The Bodyline Fix

- Book 1 Subtitle: How women saved cricket

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $34.99 pb, 304 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

Planning for an inaugural women’s test series between England and Australia began in 1931, but it wasn’t until 1934 that a fifteen-strong touring party captained by Betty Archdale (who later emigrated to Australia and became headmistress of Abbotsleigh Girls School) voyaged towards Australia. As they did so, the press speculated: would there be a repeat of Bodyline?

Few, if any, of the women had the physical capacity to bowl short enough and fast enough to endanger their opponents. Even so, any impulse to emulate bodyline bowling was quickly suppressed. The England Women’s Cricket Association – in a regrettable concession – ‘had laid down a number of measures designed to make their cricket acceptable and non-threatening to the men who controlled the game’, including the prohibition of bodyline bowling.

Off the field, the English team had ‘an Australian experience replete with indigenous encounters, sheep stations and native animals’. On the field, they dominated. Crucially, the tour had been embraced by the public, crowds at some test matches exceeding 5,000 a day.

In 1937, an Australian women’s team travelled to England for a second Ashes series. This time, the Australians triumphed, winning two of the three tests and playing over the course of the tour to more than one hundred thousand spectators. ‘We may have been able to teach the Australians something in 1934,’ Archdale recalled, ‘[but] they are now repaying us, plus a thumping interest.’

As with England’s tour of Australia, Australian cricketers were required to provide all their own equipment and contribute £75 – the equivalent of almost six months wages – to cover their costs. (By contrast, the men’s team that had recently returned from a tour to England had all their expenses covered and each was gifted a £600 bonus.) In a country still suffering from the effects of the Great Depression, such a requirement was onerous. Many of the women relied on raffles and fundraising. Others such as spin bowler Anne Palmer were unable to raise the necessary funds and were denied their place: ‘My father was not working then and there was no way we could have raised [the money].’

The tour coincided with the coronation of George VI. Stell notes her frustration that so many of the women she interviewed recalled more about the coronation (‘the most thrilling experience of their visit’) than they did about the games themselves. Also recalled in detail were the billets where the women stayed, many of them ‘posh’ houses replete with butlers and ladies’ maids that amused and bewildered them in equal measure. In anticipation, team chaperone Olive Peatfield had spent time during the voyage to England schooling some of the women in the finer points of etiquette: ‘I didn’t even hold my fork the right way,’ fast bowler Nell McLarty mused.

The light shed on issues of class is an unexpected bonus of The Bodyline Fix. Insights into class-based inequalities of opportunity – inequalities which tend to be masked in surveys of the men’s game, where the focus veers more towards statistics and strategies – are here thrown into sharper relief. Significant, too, is what these women’s stories reveal about the relationship between class and fealty to empire.

One weakness of Stell’s account is her failure to address the double-edged sword of women’s cricket associations encouraging the players to not ‘take their cricket too seriously’, as though in order not to subvert social norms too drastically, or unduly threaten the pre-eminence of the men’s game, women must situate themselves as keen and jolly amateurs. How this in turn impacted on the diminishment of the women’s game – at least in terms of its visibility – during the latter half of the twentieth century deserves scrutiny.

What makes The Bodyline Fix such a treasure is that Stell has allowed her primary sources to dominate the narrative. We owe her a debt of gratitude for having found these women and recorded their voices. Their joy and humour – and, vitally, their lack of pretence – make for irresistible reading.

Comments powered by CComment