- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Indigenous Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Sharing stories

- Article Subtitle: Turtles as meat, symbol, and material

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

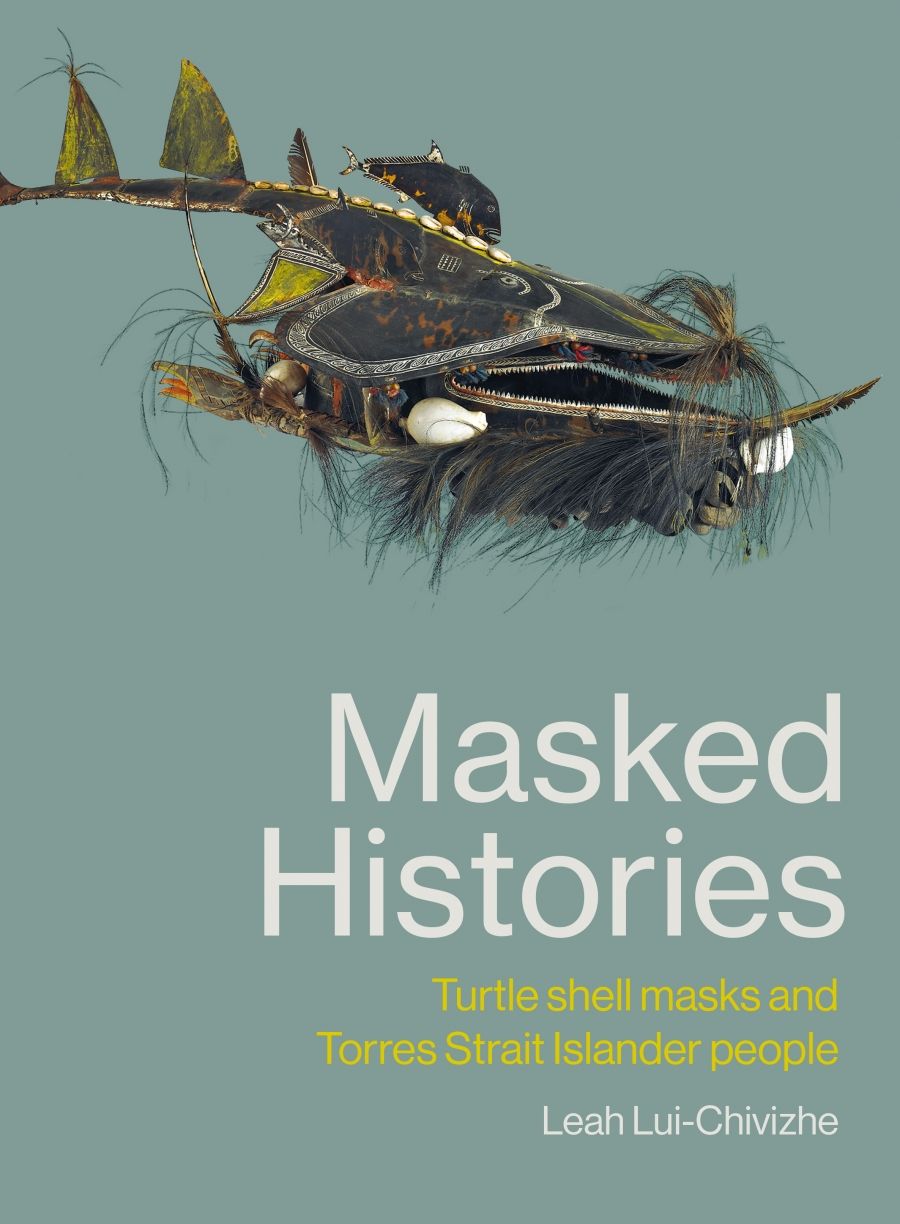

Turtles, Leah Lui-Chivizhe shows us in Masked Histories, are at the centre of Torres Strait Islander lives. They follow the Pacific currents and slipstreams, arriving in the Islands in the mating season of surlal, making available their eggs, their meat, their shells. For millennia, marine turtles have provided Islanders with material for subsistence and ceremony – allowing them to practise ceremony with turtle shell masks so evocative of Islander cultures and histories.

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Ben Silverstein reviews 'Masked Histories: Turtle shell masks and Torres Strait Islander people' by Leah Lui-Chivizhe

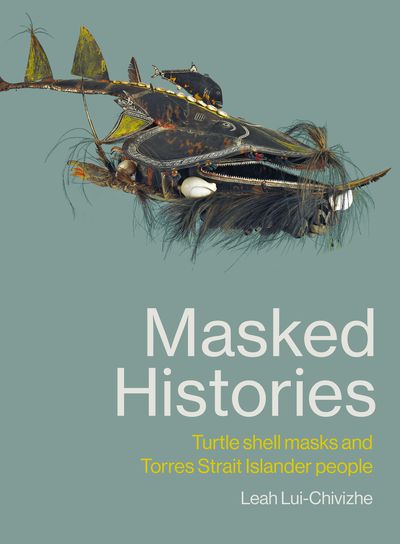

- Book 1 Title: Masked Histories

- Book 1 Subtitle: Turtle Shell Masks and Torres Strait Islander People

- Book 1 Biblio: The Miegunyah Press, $39.99 pb, 240 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Both Tipoti and Lui-Chivizhe have since engaged with masks to tell Islander stories. For Lui-Chivizhe, this book is an outcome of that work, placing turtle back in the context of ‘Islander-oriented’ histories. This re-placement and re-storying is not a simple return to a time before colonisation but represents a reorientation, working across an array of sources to reconnect these masks with their human and more-than-human histories.

Masked Histories shares stories of turtle in the Islands. It begins by mapping Islander–turtle relationships; providing a deep history of practices of hunting, butchering, and preparing, carried out by people for whom turtle is meat, symbol, and material. In chapter two, we learn that turtle were attractive to those outsiders who intruded with increasing frequency from the late eighteenth century onwards.

Chapter three turns to the story of a large turtle shell mask, adorned with human skulls and seashells and coated with red ochre, which was stolen from Auridh in 1836. Lui-Chivizhe narrates its theft and the way it was made to stand in imperial thinking as proof of the ‘murderous savagery’ of Islanders, licensing the destruction of the village from which it was taken. Clearing away this framing, Lui-Chivizhe provides a nuanced reading of the mask, not as a ‘gruesome trophy’ but as an especially significant and living ritual object once stored carefully in a ceremonial keeping place, where it would help relate sea and land, living and dead, across time and place. Masks, we learn in chapters four and five, represent enduring histories. They have the power to connect Islanders today – as they did 150 years ago – with cultural heroes and with the wisdom of ancestors. They hold and communicate valuable knowledge about Islander (and colonial) pasts. The masks themselves have agency: the Auridh mask’s power, perhaps, explains how it has survived almost two centuries in exile, through multiple fires, while its thief faced a spiral of bad luck, incapacity, and ‘depression of spirits’.

This story culminates in a wonderful final substantive chapter that shows how Islanders engage with masks today to re-story them, to become turtle, to enliven relationships between themselves and the more-than-human world, to connect with and through their history. These are different ceremonies, of creative expression, of curatorship, of social research. Frank David of Iama, for instance, devoted hours to closely examining images of turtle shell masks, carefully reading them to uncover their stories. Rosie Ware of Moa/Mer was inspired by images of ancient masks to carve their likeness into lino, printing them onto fabric. The illustrations of these and other Islander artistic responses in Masked Histories are stunning.

Masked Histories does not toy with a kind of decolonising representation in which a return to a pre-colonial past is possible. Nor does it imagine that period as a moment of authenticity prior to colonising influences. Rather it sits seriously with the life of these masks when they were in the Islands and since their removal. It imagines a future in which Islander representations can shadow imperial networks, in Tracey Banivanua-Mar’s phrase, disposing of the idea of an essential authenticity in favour of inexorable relationality; not erasing but working through the past century of dislocation to connect across place and time.

This work, in turn, transforms the stories imperial institutions tell of masks. When Alick Tipoti met the kodal krar – a turtle shell mask representing his totem, the crocodile – in that lab at the British Museum, he lowered his body and became a crocodile, making his way on all fours across the room to introduce himself. For a moment, Lui-Chivizhe writes, the British museum ‘became an Islander cultural space’ in the heart of empire. That moment endures. Tipoti’s fibreglass re-creation and response to the kaigas krar – a turtle shell mask of the giant shovelnose ray, incorporating four other totemic animals – now sits alongside the original, which was acquired by the British Museum in 1886.

Tipoti’s mask enacts relationships with ancestors and with natural and spiritual worlds. In ‘Living on Stolen Land’, Ambelin Kwaymullina describes a decolonised future based in the ‘places where different worlds meet’, when those places are refigured as sites of ‘connection, enrichment and transformation’. In gifting us glimpses of this future, Masked Histories shares with us new stories and new possibilities.

Comments powered by CComment