- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Young Adult Fiction

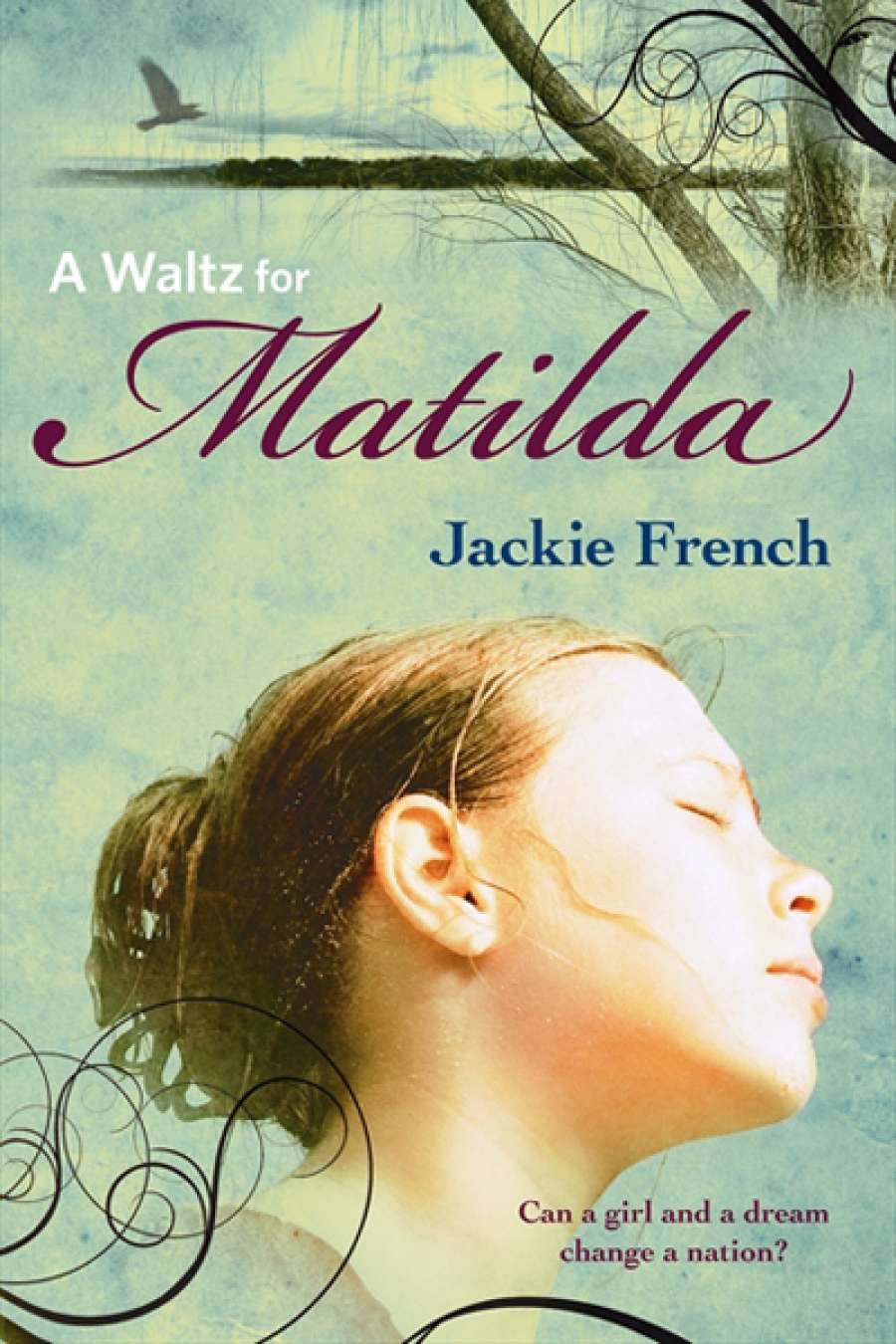

- Custom Article Title: Gillian Dooley reviews 'A Waltz for Matilda' by Jackie French

- Book 1 Title: A Waltz for Matilda

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $19.99 pb, 479 pp, 9780732290214

Immediately after reading Matilda, I had occasion to reread Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. I could not help being struck by the ways in which Matilda conforms to the heroic stereotype that Austen lampoons in that novel and elsewhere. In her ‘Plan of a Novel’, she writes, ‘Heroine a faultless Character herself, – perfectly good, with much tenderness & sentiment, & not the least Wit’. We first meet Matilda as she writes a rather prim letter to the father she doesn’t remember, informing him of their severely reduced circumstances: the aunt they have been depending upon (a stalwart of the Women’s Temperance and Suffrage League) has been crushed to death by a bullock dray. The bailiffs have taken away the furniture, Matilda has had to leave Miss Thrush’s School for Young Ladies to work at the jam factory, and she and her invalid mother are reduced to living in a squalid room in Grinder’s Alley. She respectfully points out to ‘Dad’ that ‘we have not had a postal order from you for more than a year’, and suggests that they might join him on his farm. Inevitably ‘Mum’s’ days are numbered. She drifts off with a smile on her face, but not before a horrible industrial accident puts Matilda’s best friend Tommy in hospital with serious jam burns, which would have killed him had Matilda not promptly doused him with a handy hose.

So this destitute but well-educated and amazingly resourceful girl sets off to find her father’s farm, ‘north of Gibber’s Creek’. The geography of the novel is entirely fictional, the city as well as the country, but we are told that this farm is hundreds of miles away from the city, and the train doesn’t go all the way. Undaunted, Matilda sets off, and, assisted by her innate respect for all races and classes (even those who indulge in ‘spirituous liquor’), makes her way to her father’s small farm. But the shearers’ strike is on, and her father is feuding with the local squatter, Mr Drinkwater, so they decide to set off ‘waltzing’ their ‘matildas’ till ‘things cool down’. After just enough time for the pair of them to get acquainted – to find out that it wasn’t his fault that the marriage hadn’t worked, that he wasn’t a criminal but a staunch union man – the squatter and the troopers (one, two, three) descend upon them and the rest is … well, folklore.

The difficulties of constructing a realistic novel around folk stories are obvious. It is not easy to drown yourself if you can swim, and why would you, if you’re an honourable man (which Jim O’Halloran is supposed to be) and you’ve just taken responsibility for your twelve-year-old daughter? Nevertheless, this is what French would like us to suppose happens. Matilda’s heroism is more sustained, though scarcely more credible, than the exertions Austen lampooned: she returns to her father’s farm, and with the help of the Aboriginal stockman she always calls ‘Mr Sampson’, and an elderly and infirm Aboriginal woman, she quickly builds up the property over the next few years, despite drought and the obligatory bushfire. The combination of unlikely events, historical coincidences, and novelistic clichés continues, with love triangles, heroic deaths in distant lands, and the belated revelation of a family secret which, though profoundly puzzling and mathematically incredible, explains some of the odd behaviour of some of the elderly characters. (At this point, I was irresistibly reminded of the succession of long-lost grandchildren who appear in Austen’s Love and Friendship.)

French is a professional, and she keeps her story rattling on at a good pace. The language her characters use is roughly appropriate to the period, though I can’t imagine anyone in 1894 dismissing an unwelcome visitor with ‘I think you need to go’, and I did tire of the constant use of ‘er–, biscuit’ as a coy substitute for ‘bastard’. And although Matilda is virtuously respectful towards everybody, including Chinese market gardeners and Aboriginal stockmen, French still feels the need to apologise twice – once at the beginning and once at the end – for the ‘racist words and racist assumptions that are not – and should not be – in common use today’. Actually, I would be inclined to take her to task for the opposite tendency: that of over-romanticising non-Anglos, especially Aborigines.

I can’t say I didn’t enjoy A Waltz for Matilda. Despite the clichés, Matilda is a likeable enough heroine, and French is good at creating a sense of place. The research, much of it clearly laid out in an appendix in study-guide fashion, is solid and is deployed well. The book’s length seems to indicate that it is intended for adults rather than children, but an intelligent twelve-year-old with sufficient attention span and a willingness to suspend her twenty-first century cynicism would be its ideal reader.

Comments powered by CComment