- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Mansfield was thirty-four. Having suffered tuberculosis for years, she died after hurrying up some stairs, intending to show her husband how well she was. This was at La Prieuré, Fontainebleau, house of George Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man: a sort of commune, organised around shamanic dancing, Eastern mysticism, and Gurdjieff’s compelling personality. For Mansfield, the Institute was not simply a last resort; she went there for a new beginning. In a letter to her friend Koteliansky, she wrote: ‘I mean to change my whole way of life entirely …’

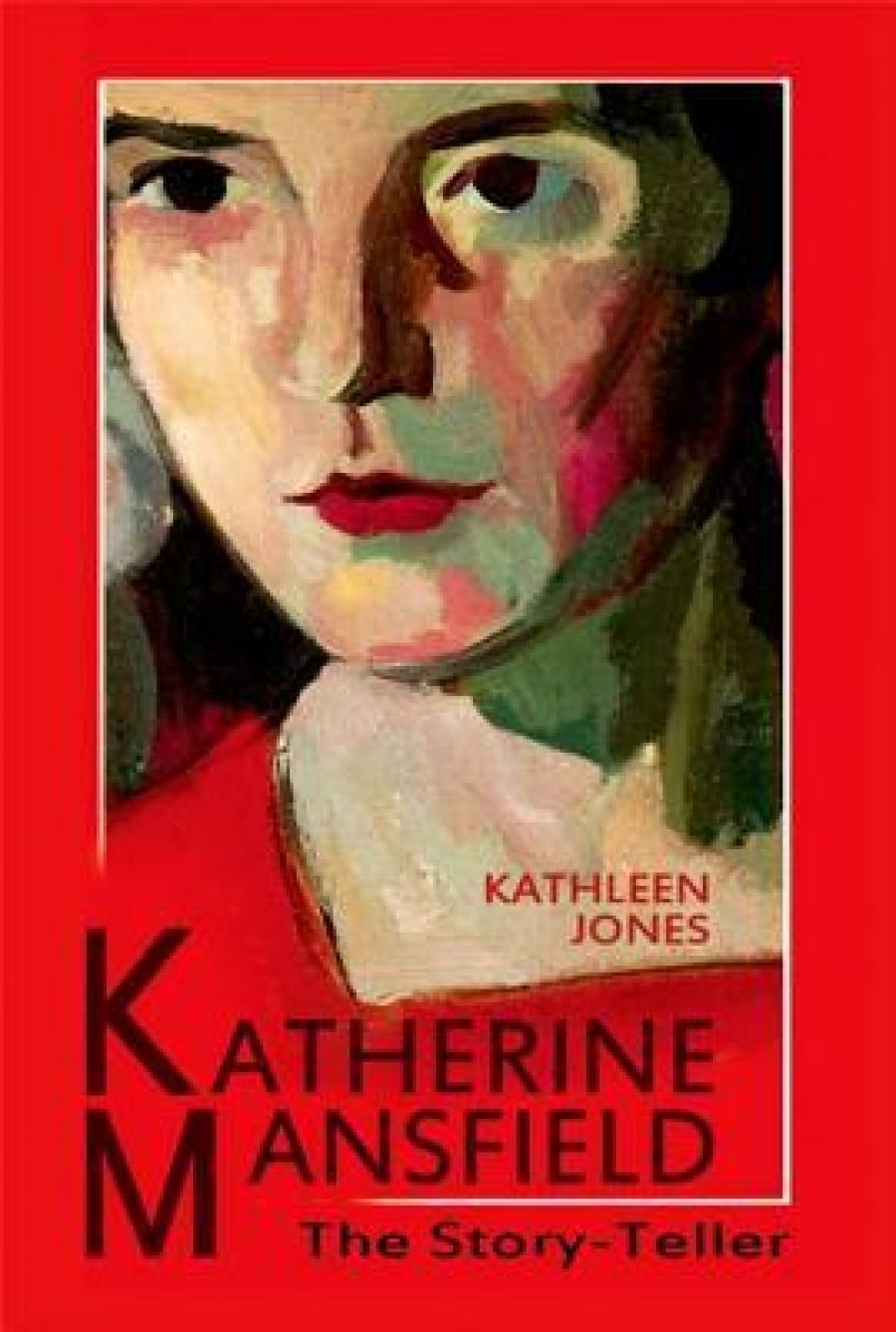

- Book 1 Title: Katherine Mansfield

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Story Teller

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $55 hb, 524 pp

Mansfield was thirty-four. Having suffered tuberculosis for years, she died after hurrying up some stairs, intending to show her husband how well she was. This was at La Prieuré, Fontainebleau, house of George Gurdjieff’s Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man: a sort of commune, organised around shamanic dancing, Eastern mysticism, and Gurdjieff’s compelling personality. For Mansfield, the Institute was not simply a last resort; she went there for a new beginning. In a letter to her friend Koteliansky, she wrote: ‘I mean to change my whole way of life entirely …’

Kathleen Jones’s new biography starts with Mansfield’s death. From that beginning, it describes both Mansfield’s life, and how her husband, John Middleton Murry, handled her afterlife – her writing. To that end, the biography works with a complex time structure. Broken into eight parts, it moves between the story of Mansfield’s life and that of Murry after her death: his three marriages, his four children, and his lifelong devotion to ‘the Mansfield myth’. Jones relates the story of Mansfield’s life in the present tense, while she tells the story of Murry’s life in the past tense. In this way, she keeps Mansfield at the imaginative centre of the book.

There are plenty of biographies of Katherine Mansfield, but Jones’s interest in ‘the husband’s story’ makes this biography distinctive. And it is true that Murry and Mansfield had a fascinating relationship: a love thwarted whenever they spent any length of time together, yet compelling whenever they spent time apart. Mansfield’s loyalty to Murry was one of the most intriguing elements of her life and character; Jones is right to concentrate on it.

Nevertheless, her patient and considerate study of Murry does not make him any easier to like. All his life, Murry thought it confusingly ungenerous of Mansfield to have wanted care, and to have minded his having affairs and writing to her about them, while she was dying. As Mansfield’s childhood literary hero, Oscar Wilde, might have said: to neglect one young wife dying of tuberculosis might be regarded as a misfortune; to neglect two looks like carelessness. While Murry was publicly grieving at Mansfield’s death – with an effusive sentimentality some took as a reflection of guilt – his talented and unassuming second wife, the writer Violet le Maistre, was dying of tuberculosis. At this point, Murry started an affair with his children’s nanny, Betty Cockbayne. He married Cockbayne eight weeks after le Maistre died. Cockbayne was brutal to the two children of Murry’s and le Maistre’s marriage, particularly after her own two children were born. The situation turned violent when Murry fell in love with Mary Gamble, who was to become his fourth and last wife. In telling Murry’s story, Jones is concerned to show how the memory of Mansfield haunted his life – and how much that haunting cost the other people who relied on him.

Jones’s biography, though it concentrates more on Mansfield’s life than on her writing, nonetheless places the work in her world; it makes clear the courage of her ambition. Many of Mansfield’s decisions make sense only in light of her commitment to writing. The first time she coughed bright red blood into her handkerchief, she wrote in her notebook: ‘I don’t want to find this is real consumption, perhaps it’s going to gallop – who knows – and I shan’t have my work written … How unbearable it would be to die, leave “scraps”, “bits”, nothing real finished.’

Mansfield refused to go to a sanatorium because she thought it would cut her off from writing. If she went to La Prieuré in search of a new life, she sought that new life partly because she thought it might help her to achieve a new writing style. Although the Woolfs thought that Murry encouraged a ‘sticky sentimentality’ in her prose, for Mansfield he was the first reader of her work. ‘Heres a confession’, she wrote to him in 1915: ‘I cannot write if all is not well with us … when I write well it is love of you that makes me see and feel …’

Mansfield left all her writing to Murry:

All my manuscripts I leave entirely to you to do what you like with. Go through them one day, dear love, and destroy all you do not use. Please destroy all letters you do not wish to keep & all papers. You know my love of tidiness. Have a clean sweep, Bogey, and leave all fair – will you?

After she died, Murry promoted her writing with a dedication that he had never in her lifetime managed. He spent the rest of his life preparing and bringing out editions of her journals, her letters, and her stories. He edited the journals and letters to present both him and her in a kinder light; but he published the stories without discrimination.

One of Mansfield’s friends thought that he was ‘boiling Katherine’s bones to make soup’. Against this, Jones records the thoughts of Margaret Scott, who transcribed all of Katherine’s letters and notebooks: ‘Only another transcriber, coming after him, can perceive the quiet dogged hard labour he put into these volumes.’ Murry’s own thoughts, recorded in a diary, reflect at once his self-absorption, his idolatry, and his desire to be more generous in his work than, in his life, his nature allowed:

Katherine is complete, immortal – not personally mine. She gave me myself by leaving me. The shock of that bereavement was the one crucial happening of my life. Everything afterwards grows out of that. And if I go down to posterity simply as the husband of Katherine Mansfield – well, it won’t be far from the truth.

‘Complete, immortal’ – Mansfield was also charming, private, skittish, quick-witted, caustic, disarming, brittle, and resilient. Her character makes a fascinating study; the interest derives in part from the difference between her journals, her letters, and her stories. Certainly, Mansfield’s journals surprised and unsettled Virginia Woolf, who had not realised her friend’s vulnerability.

Though Jones draws on all possible sources, she concentrates on the intimate character of the journal writer. Her biography traces the vexations, hurts, excitement, and rapture of Mansfield’s daily experience. Turning from Jones’s biography to the letters occasions a small shock: what a lot of ‘front’ Mansfield had, and what sly humour. At the same time, a longing for honesty complicated and disrupted her own social calculations. It also provoked the struggle she had with her writing style: ‘I feel again that this kind of knowledge is too easy for me; it’s even a kind of trickery. I know so much more. This looks & smells like a story but I wouldn’t buy it. I don’t want to possess it – to live with it. NO.’

In Mansfield’s life, that sense of difficult honesty found its place perhaps in the nature of her truest friend, Ida Baker. The two met at school in London. From that time, Baker devoted herself to Mansfield. Stubborn, tactless, and not the slightest bit chic, Baker often maddened Mansfield with her devotion. Yet, though Mansfield often railed against Baker, she did not disown her. Baker herself believed that she was a source for one of Mansfield’s two most compelling characters: the sisters in ‘The Daughters of the Late Colonel’, mysterious in their stoicism and self-renunciation. In the biography, Jones pays tribute to Baker’s position in Mansfield’s life. Yet any study of Baker emphasises, by contrast, how far Mansfield and most of the people she knew lived in and through their writing. In the story of Mansfield’s life, Baker remains one of the most intriguing characters.

If Ida Baker serves as an emblem of Mansfield’s desire for honesty, Mansfield’s courage finds its emblem in suitcases and staircases. Tuberculosis obliged her to escape English winters. But from the time she moved to London to live as a writer, she moved all the time – in search of a room where she could write, cheaper rent, a place that satisfied Murry, a more free-thinking landlady, a sense of home. To Murry, she wrote: ‘Do you remember as vividly as I do ALL those houses ALL those flats ALL those rooms we have taken and withdrawn from …’ To Ottoline Morrell, in splendour at Garsington, she complained of having to ‘climb flights of dirty stairs & shiver past pails containing dead tea leaves & bitten ends of bread and marmalade … the trace of those places seems to cling round the hem of one’s skirts forever’.

Perhaps that long unsettledness gave Mansfield’s late stories of New Zealand their particular beauty as works at once sharply real and held complete in the mind: she made her home in them. As she once wrote, ‘to change habitations is to die to them’.

Comments powered by CComment