- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

At the beginning of his new book, Terry Smith writes that one of the fundamental qualities ‘of the contemporary: [is] its contemporaneousness’. He writes of the contemporary, contemporaries, contemporaneity, contemporaneous, noncontemporaries, cotemporality, cotemporalities, and cotemporal. It is a kind of tautological word game that goes down well in academic conferenceville, which is where some of this book first appeared. The function is to distinguish art of the last two decades, called ‘contemporary’, as distinct from that of earlier periods, labelled ‘postmodern’ and ‘modern’.

- Book 1 Title: What Is Contemporary Art?

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Chicago Press, $39.95 pb, 329 pp

This desire to place the ideas and works of artists in neat boxes is one of the more irritating habits of theoretical art historians; Smith is hardly alone in his desire to categorise. But claiming ‘contemporary art’ as the label for art made at the cusp of the twenty-first century is ambitious. ‘Contemporary’ was a common descriptor for modern art throughout the United Kingdom and the former British Empire for most of the twentieth century. ‘Modern’ was more popular in Europe and the United States, although Chicago opened its Museum of Contemporary Art in 1967.

More is at stake here than mere language games. Smith is in the process of establishing himself as a key scholar of the history of contemporary art; a footnote in chapter thirteen signals that a further volume is under way. According to Smith, the reason for the importance of contemporaryart is that, unlike modernism, ‘it is, perhaps for the first time, the world’s art’.The constant use of italics for emphasis, as well as the intrusion of the first person (singular and plural) into the narrative, is a reminder of the history of this text as a spoken form, and should have been ironed out in the editing process.

Smith’s claim that recent art should be seen in a global context is fair enough in this era of instant communication and high-speed travel, and he is well placed to advance it. His dialogue with the United States began in the early 1970s, and in recent years he has divided his time between an academic appointment at Pittsburgh and maintaining Australian connections. Smith has therefore been a witness to the exhibitions and institutions that are the subject of his writing. His Australian links mean that local artists rate a few more mentions than they do in books written by Americans or Britons, but, with the exception of a discussion on the auction house market for Aboriginal art, most such references are fleeting.

The book is divided into thirteen chapters, each dealing with different aspects of the institutions, exhibitions, preoccupations, marketing, and politics of recent art. It is generally a fair synthesis of recent debate on the visual arts, albeit with a strong bias towards London and the United States. There are good reasons for focusing on the aesthetically conservative Museum of Modern Art’s Francophile linear narrative on modern art, and the way it tends to turn the intellectual rigour of Minimalism into a form of decoration; but I wish that Smith had also noticed the way in which the restructured MoMA building still effectively operates as a department store for established taste.

Nevertheless, it is the changing nature of the art market that attracts much of Smith’s attention. This seems reasonable, since the frenetic investment market for contemporary art is spectacular. There is a detailed account of Charles Saatchi and his creation of the market for YBAs (Young British Artists), the cultural heirs of Margaret Thatcher’s Britain, Sotheby’s role in boosting the market for Aboriginal art, and the changing market strategy that privileges international art fairs over sales at auction. Smith notes the absurd hyperbole of the investment spruikers, but curiously justifies their claims with a chart matching Standard & Poors investments versus art investments. On the raw figures, art wins over stocks and shares, but the simplistic nature of the graph conceals the realities of buying and selling art. Smith’s graph is for the entire art market. As anyone with elementary knowledge of the secondary art market knows, the prices go up when artists become fashionable, and go down when they are out of fashion, which is why the art market is such a trap for young players. Real profits are only available to those with the kind of knowledge that the stock exchange would regard as insider trading. One of the reasons why the art market attracts so many colourful people is that unlike the stock market, or even real estate, there is no regulation.

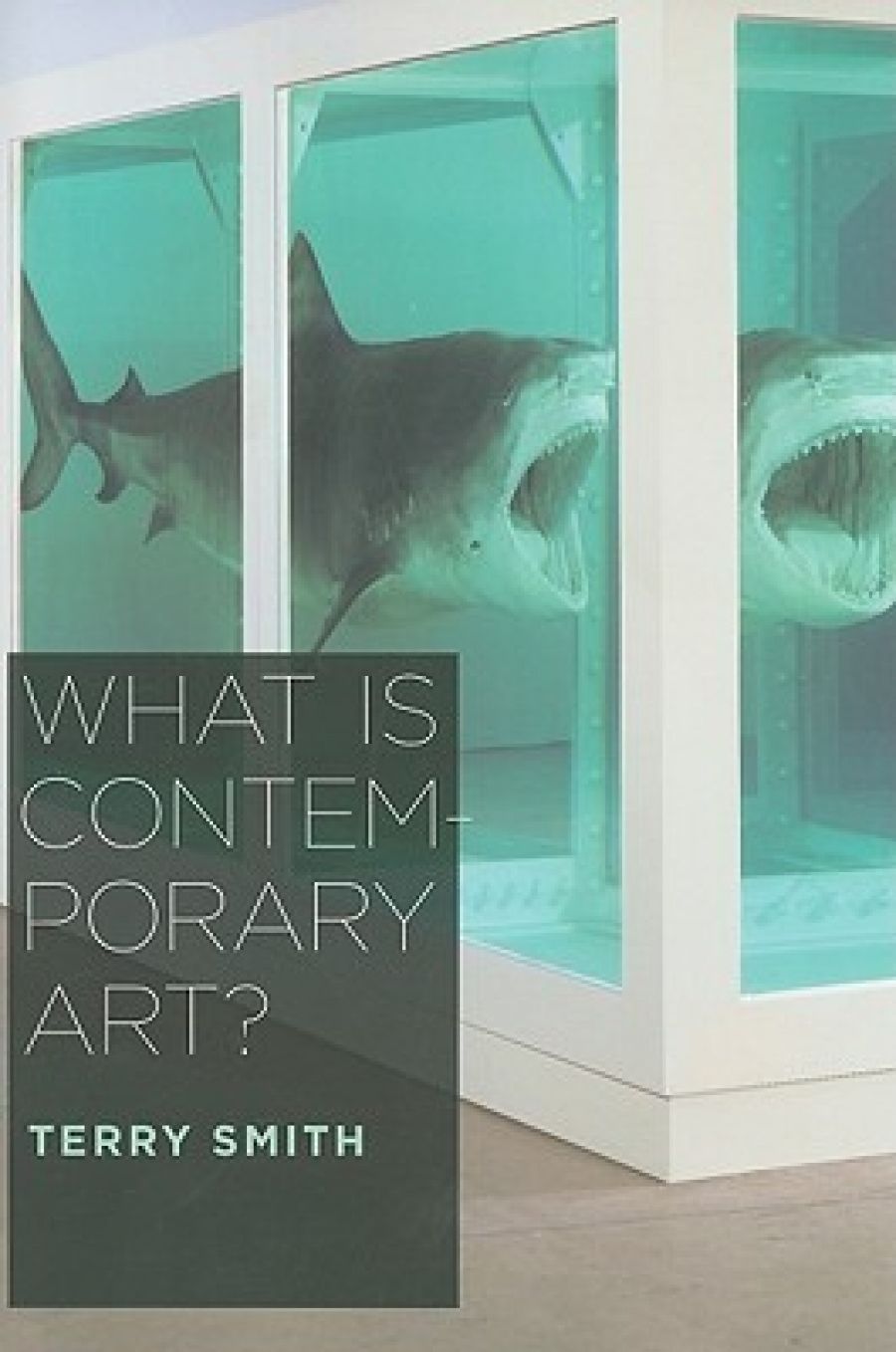

The idea of the rich rushing out to buy the latest art to demonstrate their cultural superiority is hardly new. Academic artists in the nineteenth century sold their contemporary works for excessively high prices, but most of these were condemned as kitsch within a generation. Smith examines the impact of Matthew Barney’s Cremaster cycle and notes its Wagnerian extravagance. Barney, Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, and Tracey Emin all exhibit the kind of passion for self-promotion that would happily suit that old Austrian art star Hans Makart, but although he impressed Emperor Franz Josef and much of Germany, Makart is hardly a household name today.

Smith rightly sees the current designer emphasis on grand spaces as sculptural form, where museums such as Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim at Bilbao and the Dia-Beacon in New York celebrate themselves rather than their contents. These structures are in effect sculptures, and should be treated as such. Again, this is hardly new. Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum, where Barney’s Cremaster cycle was installed/performed in 2003, is surely the acme of all sculptural exhibition spaces. The use of a giant scale, where minimalist works look their elegant best, raises another question that Smith doesn’t fully address: the fate of modernism. He claims that modernism ended some time ago, so the art Frank Serra and others have produced in recent years is ‘Remodernisation’, a dead parrot revived. There is another explanation. The art world is vast, and many ideas and tendencies can coexist simultaneously. Globalisation does not necessarily lead to a homogeneous aesthetic.

Global perspectives do, however, lead to an understanding that the world is a very interesting place where things may happen differently. Perhaps because the primary audience for this book is in the United States, this world of difference is not treated especially well. The great story of today’s art market – the marked expansion of China – is downplayed; continental Europe receives less notice than does the United Kingdom, India does not exist, and Africa is mentioned only in passing. There is a detailed and celebratory account of the Bienal de La Habana’s art administrative practices, which Smith sees as changing the way the world deals with biennales.

The sole reference to Queensland’s Asia-Pacific Triennial (APT) occurs in a list of exhibitions inspired by Havana. However, the APT was a result of Queensland’s own concerns, and the consultative model was based on that gallery’s experience in working with Aboriginal (and other) communities to create Balance 1990, one of the most innovative exhibitions ever seen in this country.

Perhaps Smith’s next book will map the many interconnected histories of current art, so that readers can learn of changes in China, the Chinese diaspora, South-East Asia and the Middle East, and in the thoughtful visual responses of central and eastern Europe. He might even notice that the United States is no longer the centre of the creative world.

Comments powered by CComment