- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: East Timor

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

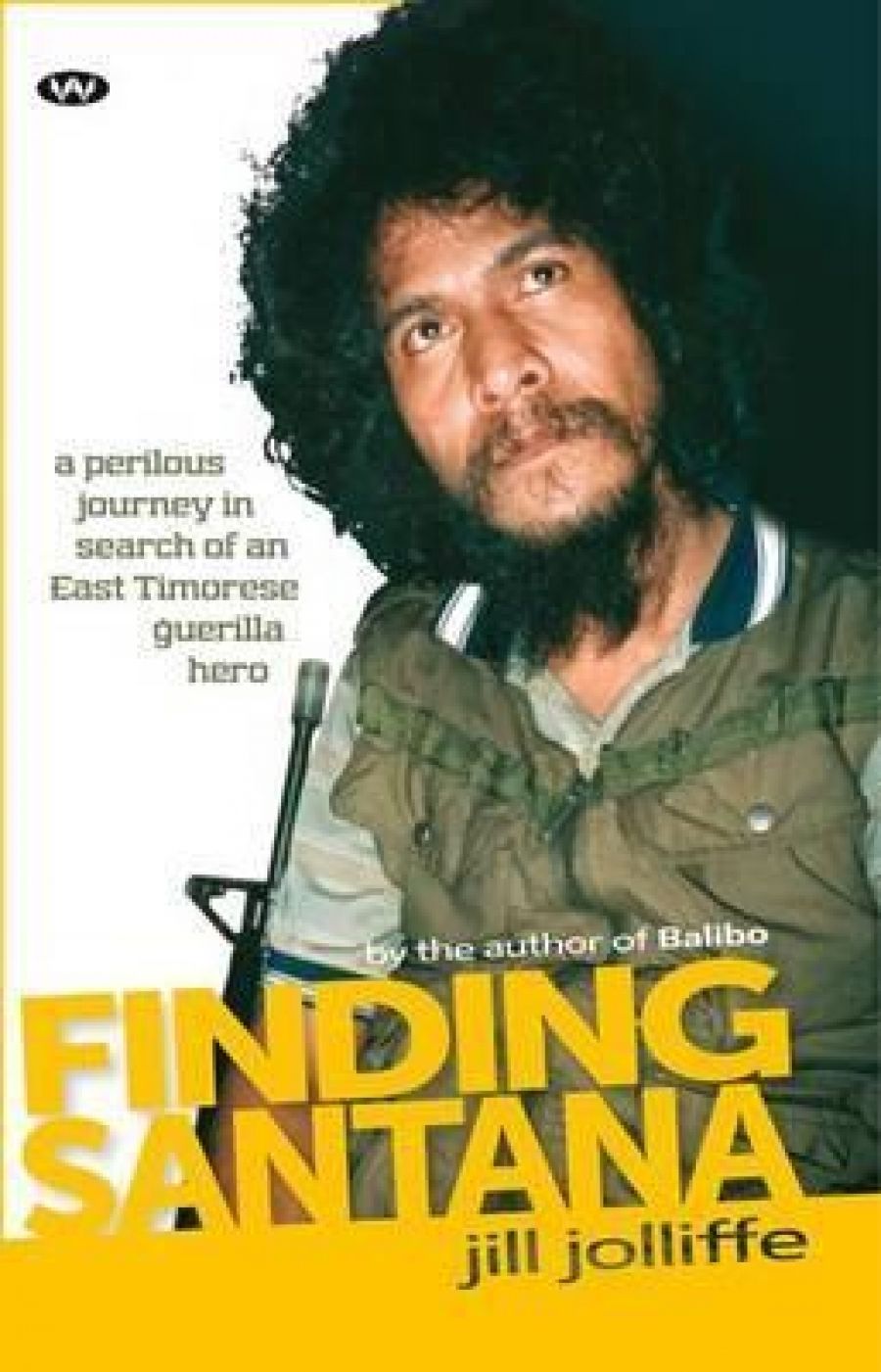

On YouTube, the guerrilla fighter Nino Konis Santana is presented Che Guevara style, in fatigues with beret and rifle, against the East Timorese flag. Villagers sing his praises in the local dialect of Lospalos, his remote birthplace. Santana, both a national and a folk hero, holds a revered place in a country which desperately needs unifying symbols. He became the rebels’ operational commander in 1993 after Xanana Gusmão and his deputy were captured, and when Santana died in the mountains in 1998 at the age of thirty-nine, José Ramos-Horta, the rebellion’s voice in exile, declared his death ‘a tragic loss for the People of East Timor’. This was the man journalist Jill Jolliffe set out to find, some four years before his death.

- Book 1 Title: Finding Santana

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $24.95 pb

Jolliffe and East Timor have been linked for thirty-five years, starting with her 1975 reporting of the Indonesian invasion of the former Portuguese Timor. Her first book, Cover-up (2001), focused on the Balibo Five, the Australian journalists killed by Indonesian soldiers. Revised as Balibo (2009), it was the genesis of the recent Australian film. She spent twenty years from 1978 based in Portugal, maintaining strong links with Timorese rebels and refugees in Lisbon and becoming increasingly angry at the stories of Indonesian repression and atrocities, such as the 1991 massacre in Santa Cruz cemetery.

Although banned from entering Indonesia as ‘a friend of FRETILIN’ (The Revolutionary Front of Independent East Timor) – her photograph graced Indonesian police stations and military posts – she determined to interview the rebels to ‘chart human rights violations’ and to ‘contribute to changing the world’s perception of the issue’. Under any circumstances, this would have been a dangerous undertaking, but Jolliffe was by now nearly fifty years old and admits that ‘fitness was a concern’. However, pressed by her Timorese friends in Lisbon (‘you can do it, Jill’), and with a new Australian passport without incriminating Portuguese stamps, a change of hair colour and style, underground contacts, and the irresistible pull of adventure, she set out. Among her problems was a tourist visa limited to eight weeks, and the fear that some resistance networks had been infiltrated by Indonesian intelligence agents.

If this sounds like the setting for fiction, Jolliffe’s vivid recounting leaves no doubt that it’s the real thing. The twists, turns and heart-stopping moments of her quest leave the eventual meeting with Santana only sixteen pages out of a total of 178, with the visa’s validity reduced to a terrifying single week. But the remainingpages tell a powerful story of her evasion of the military, helped by Timorese who despised their newest and most brutal colonisers.

To slip into Indonesia inconspicuously, Jolliffe took a local ferry from Singapore to central Sumatra. From there it was 3000 kilometres to Timor, across Java, Bali, Lombok, Sumbawa, and Flores, all to be traversed as a ‘tourist’. Much of the time she travelled alone, staying in the cheapest backpacker hotels, changing her story to suit the situation, using false names if she could avoid showing her passport. It is a pity that the book lacks a decent map of the archipelago. It is impossible to follow her route on the derisory frontispiece map; the detail of her account begs for the equivalent detail of something approaching an atlas.

Once found, Santana proves worth the trip’s torments, both for Jolliffe and the reader. A warm, shaggy figure, he welcomed Jill with a bear hug, and talked to her for many hours over several days. In an extraordinary moment, with both people stretched almost to their limits physically and emotionally, the guerrilla leader confesses to the journalist his feelings of personal inadequacy. When Santana took over the rebel leadership, it seems there was an attempt by Ramos-Horta to supervise from abroad, on the grounds that the provincial Santana wasn’t sophisticated enough to be leader. The move failed, but Santana absorbed its implication, explaining that he was ‘an illiterate barbarian’, unable to understand the necessary subtleties of diplomacy: ‘most of us only have primary school education, we have no theoretical or cultural conditions [sic] – the Indonesians call us “the illiterates”.’

Jolliffe’s description of their wretched circumstances is compelling, and explains her bitterness toward those ‘on the cocktail party circuit’. Little of the moneys collected abroad reached the mountains, and sometimes the men couldn’t fight because they had nothing to eat. They suffered from afflictions including malaria, painful tooth decay, and unextracted bullets from encounters with Indonesian soldiers (Santana had six). Villagers stole soldiers’ bullets for the rebels’ purloined weapons, but so few that fighters sometimes resorted to bows and arrows. Her articles, smuggled to Singapore and widely reported, created another focus of awareness, quoting Santana’s criticism of Australia as ‘insulting the principles of pluralist democracy it claims to uphold ... Australia is supporting Indonesia in the extermination of our people.’

Jolliffe’s second attempt to reach Santana, this time with a film camera-woman, ended in disaster, with capture by Indonesian troops, interrogations, rescue by the Australian consulate, and deportation. Her subsequent breakdown, partlydue to her feelings of guilt about inadvertent betrayals, rings as true as the rest of her story.

We now tend, perhaps, to take an independent East Timor’s existence for granted; this book describes people, including the author, who knew how overwhelming the odds against it were. The Timorese have not forgotten: in 2007 East Timor’s first national park, incorporating Lospalos, his birthplace, was named for Nino Konis Santana.

Comments powered by CComment